Politics

The rights we want

by Uditha Devapriya

Among Sri Lanka’s largely idealistic middle-class, there is an almost foolishly optimistic belief in the necessity of political reforms for much desired change. These reforms are, more often than not, framed in terms of constitutional rights, duties, checks, and balances. This is the rhetoric of term limits, small government, and separation of powers; the idea that a country’s State will function best if its powers are clipped. Once its powers are reduced, so the logic goes, people will be able to do as they want, liberated from the constraints of authoritarian bureaucracies.

From the neoliberal right to the liberal left, these ideas have caught on everywhere, to the extent of dominating policy discussions in the country. That is what unifies the JVP and the UNP in their call for the abolition of the presidential system: the notion that the problems of the country are attributable to the flaws of its Constitution.

The SJB remains divided over these issues: hence while one section of the party allied with the UNP yahapalana project rigidly hold on to these ideas, another section has become more flexible. That explains Bandula Chandrasekara’s and Anuruddha Karnasuriya’s responses to Victor Ivan over Champika Ranawaka’s position on the Executive Presidency. As their replies make clear, far from viewing it as an aberration to be abolished, the Ranawaka faction sees the presidential system as indispensable to the country’s sovereignty.

The notion that the government presents more problems than solutions to a reformist agenda rests on the classic division, made by liberal commentators, between political and civil society: a largely imagined construct traceable to no earlier than 17th century Europe. This division followed from the dissolution of feudal society into capitalist society, a process completed between the 16th and the 19th centuries. Political philosophers, from that period, drew a line between the State and the Citizen, cordoning off the one from the other. It is this phenomenon that Marx examined in his reflections “On the Jewish Question.”

For Marx, there was nothing intrinsically non-political about the feudal order: “the character of the old civil society was directly political”. The transition to capitalism signified a rupture in this order, emancipating the citizen from the government and reducing his situation in life “to a merely individual significance.” The new society made the citizen the “precondition” of the State, endowing him with certain rights separating him from the latter.

These rights were defined in terms of a freedom to do something rather than actual political emancipation. Thus, in the new State, “man was not freed from religion, he received religious freedom… [h]e was not freed from property, he received freedom to own property.” It was more or less the gospel of 17th century English liberalism; the philosophy of man at his most egotistic, or what C. B. Macpherson labelled as “possessive individualism.”

What we need to note here is that the distinction between negative and positive rights first emerged from these debates. Distinguishing between these is rather like splitting hairs, but the difference between them has to do with their aims: hence while negative rights prevent others from interfering with your freedom to do something, positive rights recognise a wider role for the government to play in addressing the needs of the marginalised. Neoliberals and even certain left-liberals belong to the former category: those who believe the State’s role is that of a Night-Watchman who sets the rules without playing the game.

Such competing conceptions of rights and freedoms survived the 19th century. In the wake of the Second World War, multilateral institutions began recognising the need to go beyond a negative definition of these ideals. Thus the Universal Declaration of the United Nations, in Article 25, lists down a number of economic necessities such as “food, clothing, housing, and medical care” it deems everyone has a right to. That it left the implementation of these rights to individual States without specifying the manner of implementation did not take away from the point that they were now regarded as a part of the new world order.

These provisions served as the basis for the two most important conventions on economic, social, and cultural (ESC) rights to be enacted in the post-war conjuncture, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (both 1966). The Stockholm Declaration of 1972 and the Rio Declaration of 1992 reflected and consolidated these developments, with an important intervention by the Czech jurist Karel Vasek (“three generations of human rights”) confirming the view that contemporary human rights exist beyond mere civil and political principles.

Yet debates between these two schools of thought continue to rage, even in Sri Lanka. Thus advocates of negative rights, who dominated economic discussions in the previous regime, bemoan attempts by human rights groups to constitutionalize ESC rights, comparing activists to collectivists no different from the most unrepentant Stalinist. Their websites and blogs put down every progressive personality, from Roosevelt to Raúl Prebisch, while promoting what Dayan Jayatilleka with characteristic élan calls “antediluvian rightwing thinkers.”

The peak, or nadir, of these put-downs came out in a recent opinion piece that compared economists critical of neoclassical economic theories and assumptions to harbingers of the plague. Reading such screeds, one can’t help but recall the kind of hysteria which dominated economic thinking during the Kotelawala prime ministry, in particular the oblique references to Communists in the Central Bank by editorials and the almost McCarthyist hounding of the likes of S. B. D. de Silva (who later left the Bank) and Rhoda Miller de Silva (who left the country, or rather was forced to) by the then government. It goes without saying that, as Dr Jayatilleka aptly observes, such thinking would find a home in rightwing regimes across Latin America, rather than in Asia’s oldest democracy.

Sri Lanka’s neoliberals are by no means alone in making hysterically crass generalisations: in its criticism of human rights treaties, for instance, the Heritage Foundation compared moves towards legalising economic rights to no less than “the 75-year communist experiment.” If a brief perusal of policy documents and political columns reveals anything, it’s the Sri Lankan neoliberal right’s barely disguised contempt for anyone who advocates a conception of rights that, as James Peck puts it, “has less to do with individual freedom and more to do with basic freedoms.” And yet, to support the latter is not to be a Communist, even less a “Stalinist”: a point yet to be appreciated by Colombo’s neoliberal economic circles.

The hysteria that determines the thinking of the latter does very little credit to their claim of knowing how to solve Sri Lanka’s economic problems. What characterises their thinking is an almost unyielding belief in 17th century European liberalism; they accept, at face-value, what political philosophers from that era are supposed to have said on various matters. That their opinion pieces are liberally littered with references to these philosophers indicates what they believe to be the way forward for Sri Lanka. But in assuming that their preferred way forward is the only path ahead for us, they sidestep two important points.

The first is the very flawed assumption that what held true for 17th century Europe will hold true for the present conjuncture. Of course the argument can be made that these notions of economic and political freedom can be adapted to any context. But then we face the second problem, one identified less by “home-grown” nationalist thinkers than by Western political theorists (to mention three: C. B. Macpherson, Domenico Losurdo, and Charles Mills): that the political system these philosophers supported, in their day, rested on institutions which are out of date and out of place today: to name just one, slavery.

Indeed, far from failing to see a contradiction between their support of liberal ideals and the realities of slavery, they passionately defended the latter and actively took part in the slave trade. Their political system, in other words, provided the foundation for their liberal ideals, even if they drew a fine enough line between political and civil society.

As Shiran Illanperuma has observed well in a series of columns recently, moreover, English liberal philosophers made their pronouncements on free enterprise and free trade, among other abstractions valorised by defenders of negative rights today, at a time when Britain was imposing un-free and unequal trade on the rest of the (mostly colonised) world. This is what Ha-Joon Chang has outlined in his work on economic history as well, most importantly the role played by tariffs – a monstrous aberration, in the books of free market advocates – in Britain’s and later the US’s rise as an industrial power.

The conclusion we can reach from these points is inescapable: that for development to occur in these parts of the world, we need to adopt a fundamentally radical conception of rights and freedoms. What Sri Lanka needs now is not a new Constitution. What it needs now is a radical reset. It needs to acknowledge that the country’s problems are not so simple as to be resolved with a piece of paper. We have gone down that path, many times.

Neoliberals and even left-liberals are only half-right in their argument that corruption has prevented development: the real question is not who engages in corruption, but who funds the corrupt. To ask that is to realise that there is no fine line between politics and economics, that Sri Lanka’s political issues are also economic, and that we will go nowhere if we do not cede more rights to its most marginalised communities.

The State has a considerable role to play, contrary to what the neoliberal and left-liberal caucus believes, in ensuring a level playing field for everyone. The solution is not to restrict access to political power, as some would suggest, but to broaden access to as many fields as possible. We need to talk more about labour rights, affirmative action, and land reforms, and less about abstract generalisations that do very little for marginalised groups. Perhaps a good starting point would be something as simple as better bus services for villages.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Old Bottles, Spent Wine

By Uditha Devapriya

With elections coming up in a few months’ time – notwithstanding Palitha Range Bandara’s outrageous remarks, to which Saliya Pieris, the former President of the Bar Association, responded thoughtfully – new coalitions and alliances are cropping up. These have pulled together the unlikeliest MPs and ideologues, who you’d never put together in the same room but who have, in the aftermath of the 2022 crisis, have unified around certain issues. Outside of the government, the consensus seems to be that we have yet to see a proper Opposition. This is the selling promise of these new coalitions: they tout themselves as that proper Opposition, the only political groups that matter.

With elections coming up in a few months’ time – notwithstanding Palitha Range Bandara’s outrageous remarks, to which Saliya Pieris, the former President of the Bar Association, responded thoughtfully – new coalitions and alliances are cropping up. These have pulled together the unlikeliest MPs and ideologues, who you’d never put together in the same room but who have, in the aftermath of the 2022 crisis, have unified around certain issues. Outside of the government, the consensus seems to be that we have yet to see a proper Opposition. This is the selling promise of these new coalitions: they tout themselves as that proper Opposition, the only political groups that matter.

The most recent of these coalitions is the Sarvajana Balaya. Led by Dilith Jayaweera, it houses a galaxy of parties, representing diverse, often disparate, interests, including Wimal Weerawansa’s National Freedom Front, Udaya Gammanpila’s Pivithuru Hela Urumaya, the Democratic Left Front, the Communist Front, and a breakaway faction from the SLPP and government called the Independent MPs’ forum. There are other groups as well, and other personalities, including attorneys and former Chief Justices. They have colourful pasts, and they have given the new formation a very colourful platform.

Rhetoric and political statements aside, however, the Sarvajana Balaya is essentially a gathering of ex-Gotabaya Rajapaksa ideologues. Many of them, like Weerawansa and Gammanpila, resigned early on from the Rajapaksa administration, before the crisis in 2022. Others, like Gevindu Cumaratunga and Channa Jayasumana, broke ranks with that regime during the crisis. The Communist Party went beyond these formations by calling for reforms and directly taking part in the aragalaya at Galle Face. When goons attached to Mahinda Rajapaksa attacked Gotagogama in May, the CPSL’s chairman, Dr G. Weerasinghe, convened a press conference condemning Rajapaksa and asking him to resign.

Dilith Jayaweera is, of course, the ultimate ex-Rajapaksist, perhaps in the same way Ignazio Silone and Whittaker Chambers were the ultimate ex-Stalinists. When the government announced 10 plus hour power-cuts and hastily imposed a curfew after the confrontation at Mirihana on March 31, Jayaweera tussled with Namal Rajapaksa on Twitter. This led to perhaps the most significant political breach for the Rajapaksa government, since Jayaweera had, since at least 2018, spearheaded Gotabaya’s campaign from the sidelines. That he has refused to come full circle, and remains critical of Rajapaksa, is intriguing. At one level, one could call him sincerer than the SLPP, three-quarters of which slung mud at the UNP in 2019 but are now content being at its beck and call every day.

Jayaweera’s party, the Mawbima Janatha Pakshaya, is an enigma. It pontificates on the need for an alternative politics. It is high on protecting national assets, and straddles between transforming Sri Lanka “into a state of unparalleled dynamism” and “drawing inspiration from our rich culture and values rooted in our ancient civilisation.” At one level, its ideology bears analogies with the East Asian brand of developmentalist nationalism.

This is not to say Jayaweera is a Mahathir in the making, though I think he is more deserving of such epithets than Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who evoked comparisons with Vladimir Putin. In any case, kingmakers are deal-clinchers. Jayaweera’s party has the money and outreach, and is tapping into both. Against that backdrop, it makes sense for the party to enter agreements and pacts with other parties. In that regard, the Sarvajana Balaya has reached a consensus with two formations: the Old Left and the ex-Rajapaksa nationalists. For the Old Left, this marks a return to form. Last year, it spoke loftily about carving a different political space, but it has now reverted to its age-old strategy of aligning with nationalist forces. Since at least 1970, that seems to have been their preferred path to socialism.

I am being harsh on the Communist Party. But I am also being fair. Such strategies once had a purpose and logic. The geopolitics of the Cold War being what they were, the Left could make a cogent case for joining Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s coalition. The Left could make as cogent a case against it, but that’s another story. The point is that Bandaranaike represented a wave of anti-imperialist socialist leaders in the Third World, who the Left thought could be nurtured and pushed towards the Left. In this, however, the Left both overestimated and undermined the force of nationalism: it believed that nationalism would eventually wither away in the face of socialism, and saw nothing wrong in compromising on its animus against petty bourgeois ideologies if they could help foment a revolution.

The great lesson of the 1960s and 1970s, not just in Sri Lanka, but also in India, Algeria, and Egypt, was that nationalism could never lay the groundwork for a socialist society. It could only overtake it. The two, put simply, could never become one: there were just too many incompatibilities and incongruences. To give perhaps the best example, when Sirimavo Bandaranaike forced the LSSP and Communist Party out of her coalition, she shored up the right-wing of the SLFP, the Felix Dias flank. And when her brand of nepotism became too strong for even her MPs, the country witnessed a mass defection to the UNP, leading from an internal shift to the right (the SLFP) to an external, and far more consequential, shift to the right (from the Senanayake to the Jayewardene chapter in the UNP).

Yet, even with all this, it was possible to justify the Left’s forays into nationalist territory. As Vinod Moonesinghe has noted in a rebuttal to Nathan Sivasambu, not even the Left could ignore the electorate and the reality of “bourgeois democracy”, which had been granted to Sri Lanka long before other colonies and territories. 1956 marked a crucial turnaround in electoral politics. It led to the bifurcation of the Sinhala Buddhist right between the SLFP and the UNP. The choice for the Left seemed hard to make here, and for a while, controversial as it was, the LSSP and CPSL joined the the SLFP. That they soon embraced, almost uncritically, the SLFP’s descent into chauvinism (“Dudleyge badey masala vadai) is certainly unfortunate, even deplorable. But politically, it was felt necessary.

Half a century on, has the Old Left revamped its strategies? From its press conferences last year, one would have assumed so. At one point there was even speculation that the Old Left and New Left – the NPP – would band together, doing away with decades of sectarianism. This, however, was not meant to be. Instead, the Communist Party and the Democratic Left Front seem to have preferred joining Jayaweera, perhaps seeing the likes of Weerawansa, Gammanpila, and Cumaratunga as comrades who will lead them to that kalunika of Sinhala politics, the congruence of nationalism and developmentalism.

This is, of course, a mirage. But it underlies a tectonic shift in local politics.

Over the last few decades, we have seen a diminution of the Old Left and, ironically, the Mahinda Rajapaksist brand of nationalism. I have contended in my articles on Jathika Chintanaya that this reflects a broader shift within Sinhala Buddhist nationalism itself. The history of the Republican Party, some would say, boils down to the descent from Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump. Likewise, the history of Sinhala nationalism has been the descent from Gunadasa Amarasekara and Nalin de Silva to the hundred or so dilettantes who claim to be their descendants but are anything but. In that scheme, the likes of Weerawansa and Gammanpila have become the proverbial last of the lot, spouting a nationalist discourse which has become predictable and passé.

Why passé? Because Gotabaya Rajapaksa, promoted as the security-sovereignty candidate, facilitated the conjunction of nationalist and neoliberal forces. This dislodged the more populist sections of the nationalist camp – which Weerawansa epitomised – empowering a political class that wields nationalist, even communalist, rhetoric within a neoliberalised economic and social space. That could of course not have been possible without the Ranil Wickremesinghe presidency, but it would not have come to pass without his predecessor’s catastrophic failures. And no matter what Gotabaya may think, it was not, as the title of his book would have us believe, a conspiracy. It was stark, clear, obvious, from day one. Neither he nor his advisors can deny their culpability there.

Jayaweera’s developmentalist-nationalist vision shares more with the paternalistic right than the democratic left, notwithstanding his embracing a party which calls itself the Democratic Left Front. What is ironic is how ideologues attached to the Communist Party see it fit to attack the NPP, but see nothing wrong in joining forces with nationalist formations that have run their course and have given way to the most nefarious political conjuncture in Sri Lanka’s post-independence history: the SLPP-UNP pact. These parties are as complicit in that conjuncture as the parties that are in power. Not all the rosy words or mea culpas in the world can absolve them, or their accomplices, of this.

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher, and analyst based in Sri Lanka who contributes to a number of publications on topics such as history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy. He can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Quo Vadis?

1: Feeding the 225

2: Don’t wait for the state; let’s act on our own

by Kumar David

This has been the most rainy and squally Vesak that I can recall in my eight decades on this planet and it has made me grumpy. The depression in the Bay of Bengal has prepared all of for the couch of some psycho-quack conning folks with fictious talk of depressions.

This essay is in two separate parts unconnected with each other; a) Feeding the 225 and b) people taking the initiative into their hands and not relying on the state.

Feeding the 225

Jesus fed 5,000 with two fishes and five loaves (Mathew 14:13-21) and you may reckon that to be a great achievement but he did it only once. Our people in Sri Lanka have to keep feeding the 225 day-in-day-out every day of their lives. And where does it all go? Into political pockets! Import permits for luxury cars, insurance cover for wives, mistresses and sons and of course plain rip-off.

A sharp middle-aged lady mounting the steps of the Dehiwala-Galkissa Municipal Council alerted me. “Why madam do you look unhappy?” I foolishly asked only to be told-off in pristine Sinhala: “Aiyo, 225-ta kanda dena oone ne” (We have to fed the 225, don’t we). Only then did the penny drop. Bribes to left of us, bribes to right of us! The 225 themselves, their catchers and hangers-on (petrol allowances, salaries for aides and drivers), liquor shop permits and Gamage-type rackets that the SJP pretends it knows nothing about). In total the 225 may be cashing in a few million rupees per MP per annum. How many MPs in the current parliament are clean of such nefarious behaviour? I think less than a dozen.

Now that I am about it, a little more politics. I was, I think, the first person who more than a year ago said very firmly that the presidential election would come down to a race between RW and Anura; and it has. Sajith is wailing in the wilderness and the SLFP and SLPP are weighing the prospects of whether to line-up in the RW or Anura camps. Neither SLFP nor SLPP dare put forward a candidate of their own for fear of being wiped out and polling a miniscule number of votes. It seems increasingly likely that both will plonk into the RW camp.

Buffalo Lal Kantha’s pronouncements have made this more likely. He has in addition claimed that only the JVP and the Udaya Gammanpila party took a stand against the Tamils, opposed any form devolution and supported the military in the war against the Tigers. The import of his words is this. The JVP-NPP is going to be identified at the polls as a Sinhala party and this will have consequences. Will it draw the already radicalised Sinhala-Buddhist youth in larger numbers into the JVP camp or will it damage the JVP’s image? Time will show.

The upper and business classes and the city middle classes are cheering for Ranil. They are hooked on the idea he will be able to deliver economic growth. The Economic Transformation Bill and the Public Financial Management Bill tabled in Parliament on 22 May are intended to reassure the IMF that the road to reform that the Fund has demanded will be diligently implemented. The Fund will then unlock billions of dollars now blocked and also expedite deals with Sovereign Wealth Funds deemed necessary it is claimed to reassure the IMF and international capital. The Governor of the Central Bank is singing the same tune and has joined Ranil’s choral group. It is likely that the duo will float the rupee open-up the economy and privatise galore in the coming period. This will have political consequences.

Let me make a summary of the principal tasks facing the nation.

1. It is conventionally opined that debt restructuring, unlocking billions of dollars in IMF Funds and reaching agreement with Sovereign Bond Holders (profit seeking finance companies) is sine qua non.

2. Increasing earnings from foreign trade, meaning increasing earnings from export (including remittances and tourism) and limiting imports (except production machinery and raw materials for production), is considered vitally important.

3. Frugality in consumption (to the extent feasible with poverty ravaged masses) is desirable.

4. These three steps will it is hoped attract foreign investment into productive sectors.

None of this is new, it is all the subject of interminably long and boring newspaper columns. (When will our columnists learn that brevity is the soul of wit?)

RW is singing along to this tune and his confidence in saying NO to parliamentary elections before or simultaneously with the presidential poll shows that he believes he is playing from a strong hand. He is indulging in populist measures like issuing free-hold land title-deeds to landless Tamils in the Kilinochchi area, making attractive promises about enhancing facilities at the Jaffna Hospital, and insisting that plantation companies honour his pledge to workers of a minimum wage of Rs 1,700 per day. RW is gaming that in a presidential election well over one and a half million Ceylon Tamils, Upcountry Tamils, Muslims and Catholics will vote for him and tip the scales in his favour. (See note below). In the parliamentary elections that will inevitably follow the winner of the presidency will carry the day.

A racist alliance called the Sarvajana Balaya has, in the meantime, raised its head, led by Weerawansa and Gammanpila. It has attracted bankrupt ex-leftists of the Communist Party and ageing Vasudeva. This too will play right into RW’S hand.

Act independently

An ever-increasing number of organisations have taken matters into their own hands and launched initiatives because the government is flat-footed. Let me give you a few examples. Fed up with the inability of successive governments to do anything to combat communal violence, or to be more accurate because of the aggravation of communalism by governments beginning with the denial of citizenship to Tamil plantation workers by D. S. Senanayake, the father of the nation (sic!), through SWRD’s communal politics and JR’s loathing of Tamils, to Chandrika playing politics, a bunch of Buddhist monks took the initiative into their own hands.

The monks went on an expedition to Europe and the US, sought out Tamil links such as the Global Tamil Forum and others and initiated a dialogue. The initiative is now in motion and grass-roots activities are in full swing. Important figures like Karu Jayasuriya (former Speaker), Austin Fernando, Sarvodaya, Jehan Perera’s National Peace Council and Pakiasothy Saravanamuttu’s CPA are involved. Branches have been established in many localities and an active movement is in swing. If communal violence is to be halted and if the state and government are, quite literally, worse than useless, a grass roots people’s movement is needed. It has ben launched ; its name is National Movement for Social Justice.

A second example is the need to foster English language competence in all children as a link language between communities and more important because English is the linguafranca of the world today. (Sounds a bit contradictory, doesn’t it? Wonder what the French feel about the juxtaposition?). Seriously though, English is not just the language of modern technology and business. No, it is in all its pronunciations and accents it has become the 21st Century’s world language essential for everyone. State and government have simply and literally messed up English in Sri Lanka’s schools. So well-intentioned voluntary organisations, often women’s groups, have stepped into the breach.

Two more quick examples and I will stop. Microfinance is now the domain of groups, often women’s societies that have filled the gap since the banking sector has failed to support small and medium enterprises. And finally, cooperatives are providing marketing and investment openings for fishermen. I personally know of one such successful assembly of such entities in Jaffna.

The subject of this part of the essay however is in what ways can the people themselves, organised in various voluntary bodies, do to overcome or replace a sluggish state. To what extent can, for example a popular Peoples’ Planning Council, replace the hiatus created by the absence of a State Planning Agency in Sri Lanka. I think a popular public initiative of this nature can achieve quite a bit.

NOTE: The absolute core Sinhala vote in the country is the infamous “69 lakhs”; maybe 70 now by natural increase. I reckon that the minorities – Ceylon Tamils, Upcountry Tamils, Muslims and Catholics – are about one third of the core Sinhala vote. That is (1/3) x70 about 23 lakhs. This is why I reckon that RW is making a play for a clear majority of this 23-lakhs in the presidential poll.

Features

Police, Politics & The Rule of Law:The Great Betrayals

By Dr. Kingsley Wickremasuriya

Preface

Sri Lanka Police Service is the premier law enforcement agency on the Island and one of its oldest government establishments counting over one and half centuries of existence. During this long history, 36 Inspectors-General of Police – 11 of them from the Colonial Administration, and the rest thereafter – were in charge.

Their periods of office were characterized by riots, coups, insurrections, terrorism, political violence, trade union action, mass protests, and worst of all, the politicization of the institution. The vicissitudes the police had to face were many.

The thrust of this essay is to show how once a force that worked according to the rule of law during the colonial administration turned partial and eventually became an apparatus serving political interests rather than those of the common man. Party politics crept into the picture with the progressive introduction of constitutional reforms. To substantiate his thesis, the writer will draw selectively from material available on various websites and other archival material including Police Commission Reports.

The Portuguese – Dutch Period

The Maritime Provinces of Ceylon were under the Portuguese after their invasion in the 15th Century. The Dutch, who arrived in Sri Lanka in 1602, were able to bring the Maritime Provinces and the Jaffna Peninsula under their rule by 1658. Although they controlled certain areas of the maritime provinces, they did not carry out any serious changes to the existing system of civil administration of the country. The concept of policing in Sri Lanka however, started with the Dutch who saddled the military with the responsibility of policing the City of Colombo.

In 1659, the Colombo Municipal Council (under the Dutch) adopted a resolution to appoint paid guards to protect the city by night. Accordingly, a few soldiers were appointed to patrol the city at night.

They initially opened three police stations, one at the northern entrance to the Fort, a second at the causeway connecting the Fort and Pettah, and a third at Kayman’s Gate in the Pettah. In addition to these, ‘Maduwa’ or the office of Dissawa of Colombo who was a Dutch official at Hulftsdorp, also served as a police station for these suburbs. Thus, it was the Dutch who established the earliest police stations and thus became the forerunners of the police in the country.

The British Period

The Dutch surrendered to the British on February 16, 1796. After the occupation of Colombo by the British, law and order were, for some time, maintained by the military. In 1797 the office of fiscal, which had been abolished was re-created. Governor Fredrick North, having found that the fiscal was over-burdened with the additional duty of supervising the police, obtained the concurrence of the Chief Justice and entrusted the Magistrates and Police Judges with the task of supervising the police.

In 1805 police functions came to be clearly defined. Apart from matters connected with the safety, comfort, and convenience of the people, these also came to be connected with preventing and detecting crime and maintaining law and order. The rank of police constable (PC) was created and it came to be associated with all types of police work. By Act No. 14 of 1806, Colombo was divided into 15 divisions, and PCs were appointed to supervise the divisions.

First Superintendent of Police

Mr. Thomas Oswin, Secretary to the Chief Justice, was appointed the first Superintendent of Police of Colombo. Mr. Lokubanda Dunuwila, who was the Dissawa of Uva, was appointed as the Superintendent of Police for Kandy. He goes into history as the very first Lankan to be a Superintendent of Police.

In 1847 the ranks of Assistant Superintendent of Police and Sub Inspector of Police were created. Inspector De La Harpe was promoted as the first Assistant Superintendent of Police.

The National Police

Robert Campbell, KCMG, was the first Inspector General of Police of British Ceylon. The Governor, who was looking for a dynamic person to reorganize the police on the island, turned to India to obtain the services of a capable officer. The Governor of Bombay recommended Mr. G. W. R. Campbell, who was in charge of the “Ratnagiri Rangers” of the Bombay Police, to shoulder this onerous responsibility.

After serving as chief of police in the Indian province of Ratnagiri, Campbell was appointed by Governor Frederick North on September 3, 1866, as Chief Superintendent of Police in Ceylon, in charge of the police force and assumed duties on September 3, 1866. This date is thus reckoned as the beginning of the Sri Lanka Police Service.

Campbell is credited with shaping the force into an efficient organization and giving it a distinct identity. He brought the whole island under his purview and the police became a national rather than a local force. In 1867, by an amendment to the Police Ordinance No. 16 of 1865, the designation of the Head of the Police Force was changed from Chief Superintendent to Inspector-General of Police. In 1887 he was awarded the CMG. On his retirement, he received a knighthood for his service.

Apart from Campbell, 35 others were in charge of the Police Force in Sri Lanka. They performed to different degrees of standards contributing to the development or the decline of the police service in Sri Lanka. Cyril Longdon, the sixth Inspector-General was instrumental in establishing a Police Training School for recruits and a Criminal Investigation Department.

Ivor Edward David was the seventh British colonial Inspector-General of Police in Ceylon (1910-1913). During his tenure, David was noted for establishing the POLICE SPORTS GROUNDS in Bambalapitiya in 1912. Dowbiggin succeeded him as Inspector-General of Police.

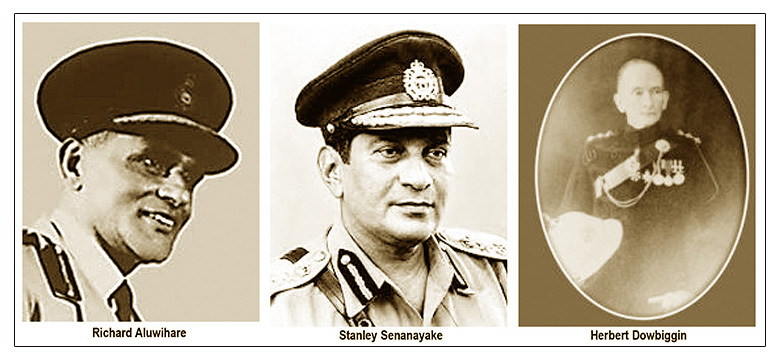

Sir Herbert Layard Dowbiggin, CMG, was the eighth British colonial Inspector General of Police of Ceylon from 1913 to 1937, the longest tenure of office of an Inspector General of Police. He was called the ‘Father of the Colonial Police’. Dowbiggin joined the Ceylon Police Force in 1901 and became Inspector General in 1913.

During his tenure, the strength of the force was enhanced considerably with the posts of two deputy inspectors general were created. He oversaw an expansion of the force: the number of police stations increased so that by 1916 there were 138 all over the island. He also modernized the force, introducing new techniques of investigation such as fingerprinting and photography; improving the telecommunications network for the police as well as increasing the mobility of the force. The analysis of crime reports became more systematic. He purchased the land on Havelock Road, Colombo, on which the Field Force Headquarters and the ‘Police Park’ playing fields are located. He was knighted in 1931.

First Sri Lankan Inspector General

Beginning with Sir Richard Aluwihare, KCMG, CBE, JP, CCS, 25 others served as IGPs thereafter. Sir Richard was a Sri Lankan civil servant and the first Ceylonese IGP who later served as Ceylon’s High Commissioner to India. The Police Department, which was under the Home Ministry, was brought under the purview of the Defense Ministry during his tenure.

Sir Richard faced the unenviable responsibility of transforming the police from its colonial outlook to a national police with the gaining of independence in 1948. To this end, he introduced a large number of innovative measures embracing the welfare of the men, investigation, prevention, and detection of crime, the women police, crime prevention societies, rural volunteers, police kennels, public relations, new methods of training and improvement of conditions of service.

He transformed what was a Police Force into a Police Service. Its role was narrowly defined and restricted to the maintenance of law and order and the prevention and detection of crime. In 1948 he established the Police Training School in Kalutara.

He retired from the civil service as IGP and was succeeded by his son-in-law Osmund de Silva. Santiago Wilson Osmund de Silva, OBE was the 13th and the first Ceylonese career police officer to become Inspector-General of Police (1955–1959). In 1955 he succeeded his father-in-law, Sir Richard Aluwihare to be appointed IGP. He became the first IGP appointed from within the police force and the first Buddhist. He introduced community policing to the country, a vision not shared by his successors.

The Great Betrayals

It was during his tenure that Prime Minster Bandaranaike is reported to have exhorted IGP Osmund de Silva that the police should have that ’extra bit of loyalty’ to the government. The response to this by the IGP was an exhortation to his officers that what they should uphold is the Rule of Law. He said this knowing that he would be falling out of favour with the premier and that it would affect his tenure. This assertion by the IGP came when there was no Bill of Rights in the Parliament or no Republican Constitution with Fundamental Rights to fall back on.

Thereafter, when the Prime Minister, S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike requested that the police intervene against trade union action occurring at Colombo Port. De Silva declined to do the PM’s bidding on the basis that he believed the request was unlawful. On April 24, 1959, de Silva was compulsorily retired from the police force with M. Walter F. Abeykoon, a senior public servant, appointed in his place.

This was the first betrayal by the head of government ignoring an entrenched police norm held sacrosanct through almost a century by the colonial administrators. It eventually led to a near mutiny by the police top brass and later even to more serious consequences of a coup the government managed to avoid by a stroke of luck.

Morawakkorakoralege Walter Fonseka Abeykoon served IGP between 1959 and 1963. He was appointed to this position May 1, 1959 by his personal friend and bridge partner, Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. The appointment was highly controversial as the PM appointed Abeykoon from outside the service by-passing several senior career police officers, on the basis that Abeykoon was a Sinhala Buddhist.

Senior police officers protested and DIG C. C. Dissanayake tendered his resignation, which was later withdrawn. The senior police officers, who were predominantly Christian, fearing a calamity, met to consider their options. They considered whether the entire police executive resigned on masse, although they decided against this as they thought it had the potential to cause the entire police service to collapse. Alternatively, they surveyed the Executive Corps for the senior- most officer among them who was a Buddhist and could find only young SP Stanley Senanayake.

They resolved to make representations to the Prime Minister that they were prepared to work under Stanley who was junior to all of them rather than having to work under an outsider with no experience who knew nothing of Police or the Police Ordinance. Bandaranaike however ignored their representations and appointed Abeykoon. In 1962, when a coup d’état was attempted by senior officers of the military and police, Abeykoon was caught off guard. Early warning from one of the conspirators, however, allowed the government to respond in time. Ironically, Stanley Senanayake was the whistle blower and the information was conveyed to IGP Abeykoon by P. de S. Kularatne, Senanayake’s father-in-law.

Thereafter, Benjamin Lakdasa ‘Lucky’ Victor de Silva Kodituwakku was appointed as the Inspector General of Police on September 1, 1998 by President Chandrika Kumaratunga following the retirement of Wickremasinghe Rajaguru on August 31, 1998 . This was a controversial appointment, his being selected over five other DIGs with greater seniority. Allegedly this appointment was influenced by the ruling party.

Kodituwakku, while in charge of the Kelaniya Police Division as SP, received transfer orders to go into charge of the Jaffna Police Division. He tried his best to get the transfer canceled but the department stood firm on its policy decision that every police officer needed to serve Jaffna for one year during the LTTE threat.

He opted to leave the service in 1984 resigning his post when he failed to circumvent the transfer. Following his resignation, he worked as a security consultant in a private company and was out of the Police Service for over one-and-a-half decades.

However, following the election of the People’s Alliance government at the 1994 parliamentary elections the new government enabled public servants who had faced alleged “political victimization” to appeal for reinstatement and back wages. Making use of this opportunity Kodituwakku re-joined the service and on October 1, 1997, was promoted to DIGl and Senior DIG rank on August 2, 1998 (a double promotion, from the rank of SSP ignoring the fact that he refused to go on transfer to Jaffna and resigned defying a mandatory policy decision taken by the Department that applied to every servicing police officer.

Kodituwakku was the Inspector-General at the time the Waymaba Provincial Council Elections took place. He was blamed for the violence and the election malpractices that took place during the elections. The 17th Amendment to the Constitution was the result of a political initiative launched by Members of Parliament in the Opposition led by the United National Party in 2001 as a response to the Wayamba Election Episode.

This was the second betrayal by a Head of State- President Chandrika Kumaratunga- when she decided to appoint Lucky Kodituwakku the 26th IGP ignoring so many other seniors over him just because of the special position he enjoyed as the Personal Security officer (PSO) of a VVIP that gave him an advantage over his seniors to canvass for the post. Wayamba- election- bungling and the 17th Amendment to the Constitution was the result.

These precedents led to yet other betrayals last of which was when Deshabndu Tennakoon came to be appointed by the current President Ranil Wickremasinghe as the 36th IGP even though the Supreme Court held that Deshabandu was guilty of human rights violations.

Tennakoon Mudiyanselage Wanshalankara Deshabandu Tennakoon (born 3 July 1971), known as Deshabandu Tennakoon is the current Inspector General of the Sri Lankan Police.

On 14 December 2023, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka ruled that Tennakoon and two of his subordinates were guilty of torturing Weheragedara Ranjith Sumangala of Kindelpitiya for alleged theft and thereby violating his fundamental rights when the men were in uniform attached to the Nugegoda Police Division in 2010.

The Fundamental Rights Application (SC/FR 107/2011) was filled by Sumangala in the Supreme Court in March 2011, against the then Superintendent of Police, M.W.D. Tennakoone, Inspector of Police Bhathiya Jayasinghe, then OIC (Emergency Unit) Mirihana, Police Officer Bandara, former Sergeant Major Ajith Wanasundera of Padukka, and several others in the police department. The three bench panel consisting of Justices S. Thurairaja, Kumudini Wickremasinghe, and Priyantha Fernando, directed the National Police Commission and other relevant authorities to take disciplinary action against Tennakoon and two of his subordinates.

On 29 November 2023, President Ranil Wickremesinghe however, appointed Tennakoon as acting Inspector General of Police. He was appointed as the permanent Inspector General of Police on 26 February 2024.

The same day that he was appointed to the post of Inspector General of Police, Leader of the Opposition Sajith Premadasa claimed that the Constitutional Council, which oversees high-level appointments, saw only four votes cast in favor of Tennakoon. In comparison, two votes were cast against and there were two abstentions. Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, counting the abstentions as votes against exercised his casting vote to break the tie in Tennekoon’s favour. This matter is currently being canvassed in the Supreme Court.

(To be continued)

kingsley.wickremasuriya@gmail.com