Features

The COVID-19 Pandemic in Sri Lanka: Contextualising it geographically

By Dr. Nalani Hennayake and

Dr. Kumuduni Kumarihamy

(Continued from Friday)

The statistics and information aside, what this tells us is that the hope for immunization through a vaccine for the coronavirus could be far off than we think. Dynamics of vaccine politics exists within global politics and the capitalist economy. The Drug Controller General of India has approved the Oxford COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and another by the Indian manufacturer Bharat Biotech for emergency care. During his recent visit to Sri Lanka, India’s Foreign Minister had pledged that India would prioritize Sri Lanka when supplying vaccines to other countries. In the same meeting, the Indian Foreign Minister had reiterated “India’s backing for Sri Lanka’s reconciliation process and an ‘inclusive political outlook’ that encourages ethnic harmony while the Sri Lankan Foreign Minister rejoiced in the merits of ‘Neighbourhood First Policy’.” At the same time, it was reported that Sri Lanka is making plans to sign an agreement to secure the COVID-19 vaccine through the COVAX facility, which is already approved by the Cabinet.

Various news reports indicate that Sri Lanka is discussing whether to obtain the vaccines from the United States, Britain, or Sputnik V vaccine from Russia. However, it is clear that Sri Lanka has entered into world politics of vaccines. Such vaccine politics tells us that we need to steadily continue controlling strategies such as social distancing, contact tracing, antigen, and PCR testing, significantly raising awareness at the micro-community level. The kind of resilience that local people display when a family member undergoes an infectious disease such as measles and mumps are remarkable. People must be reminded of their resilience and caring. The communities must be made aware of the importance of safeguarding against the coronavirus, given its increased politicization and uneven possibilities of immunization and care.

While it is difficult to anticipate an equitable distribution of the vaccines globally, Sri Lanka’s situation will be determined by the number of vaccines received and the pandemic’s increased politicization. The WHO recognizes four categories of vulnerable persons/groups: Persons at risk of more serious illness from COVID-19, persons or groups with social vulnerabilities, persons or groups living in closed settings, and persons or groups with a higher occupational risk of exposure to the virus. What guarantees that these groups will be considered on a priority basis and the process of immunization will not be biased towards economic and political power? The global geographies of vaccines communicate to us two important messages. First are the difficulty and the disadvantaged position of obtaining vaccines for Sri Lanka as a less-developed country, and as a result, the COVID-19 pandemic can be protracted. Until the vaccines are obtained and a sizeable population of, at least, the risk category – including the frontline health care and security personal – are immunized, we will automatically be identified as vulnerable territories in terms of bio-security. Second, this vulnerability can be manipulated politically, both globally and nationally, to negotiate other deals with powerful countries to trade with vaccines.

The possibility of uneven geographies of care is a fact that should be anticipated given that a majority of the infected are from what we call ‘low-income, low-social status’ communities. There is now a tendency to identify COVID-19 as a disease of the impoverished. The local government bodies such as Municipal councils must reevaluate their position, not how they have acted to control the pandemic, but what they have failed to do in addressing the social welfare issues of the urban low-income communities.

As we look at the possible geographies of care, it is evident that the existence of a relatively good hospital network (at national, regional, and local levels) with relatively good coverage of the entire country has been immensely helpful in treating and caring for COVID-19 patients and those suspected. In addition to the already existing hospitals, the government has converted various government institutions into treatment centres in different parts of the island. This provides breathing space for the government hospitals when dealing with COVID-19 patients and patients who need critical medical care for other illnesses. It should also not be forgotten that the Public Health Inspectors were a category of lesser-known among the hierarchy of the health workers. Their role in curtailing the COVID-19 pandemic has been indispensable: Working not under the best of circumstances and with the minimum personal protective equipment. The average labourer who was entrusted with the strenuous task of sanitizing public places must be cared for too.

The public health system operationalized through MOH areas, a total of 347 MOH areas, as per the Annual Health Statistics Report 2017, is an essential component of controlling the pandemic now or in the future. The health sector generally receives only 1.59 percent of the GNP and 5.94 percent of the National Expenditure, a measly share for an essential sector. According to the same Report, Sri Lanka records an acute shortage of health personnel. There is a significant shortage of nurses and doctors: One doctor for 1083 people, one nurse per 471 people, one Public Health Midwife for 3533 people. As we look into the possible geographies of care, the significance of Primary Health Care Units, the MOH-based public health system, in maintaining a healthy country is indisputable.

Micro-geographies of COVID-19

In its interim guidance issued on May 18, 2020, the directive issued by the WHO is as follows: “Physical and social distancing measures in public spaces to prevent transmission between infected individuals and those who are not infected, and shield those at risk of developing serious illnesses. These measures include physical distancing, reduction or cancellation of mass gatherings and avoiding crowded spaces in different settings (e.g., public transport, restaurants, bars, theatres), working from home, and supporting adaptations to workplaces and educational institutions. For physical distancing, WHO recommends a minimum distance of at least one meter between people to limit the risk of interpersonal transmission.” Thus, the WHO recommendation includes two components: physical distancing of one meter between people and social distancing as much as possible in the social events, gatherings, etc.

This requirement was initially communicated as social distancing (සමාජ දුරස්ථභාවය) in Sri Lanka. The exercise of ‘physical and social distancing’ during COVID-19 reminded us of the work of two Political Geographers, Robert E. Norris, and L. Lloyd Haring. They argued that “every person has [is] a portable territory that is larger than the space s/he physically needs” (1980:9). They further wrote that “This territory is called personal space. It is similar in some ways to a political territory. Both personal space and political space are bounded, occupants of each type of space interact with each other of their kin, and uninvited intruders in both types of areas cause stress and behavioural changes within the intruded area.” It is imperative to understand that the personal space or the portable territory is unique to each individual in both size and shape, and they may vary over time and space, according to their specific individual requirements. In such a situation, how can we/how do we regiment this personal space in fear of the uninvited intruder of the coronavirus pathogen, through a standard measure of one or two meters between individuals? Until the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, this space, the portable territory of ours, had been taken for granted. We operated with a sense of relative autonomy over our portable territories. Now, we are told by the state and those in charge of controlling the pandemic how to operate these portable territories, maintaining a distance of one to two meters from each other. It is also expected that every person would carry out this ‘social distancing’ uniformly.

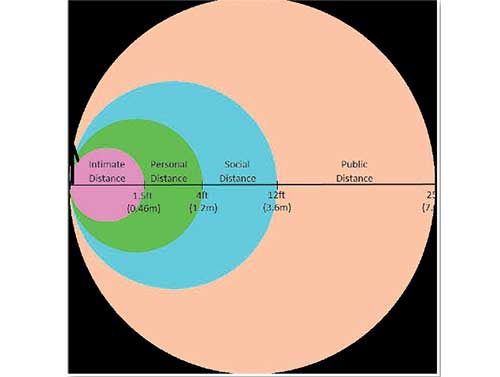

In early years, geographers were influenced by the science of spatial distancing, proxemics, introduced by the Cultural Anthropologist Edward T. Hall, who studied proxemics to understand human spatial behaviour at a micro-scale. In his famous book, “The Hidden Dimension,” published in 1966, he introduced a typology of human spatial distancing. This typology classifies the micro-spatiality of human beings into four types of spaces: intimate space, personal space, social space, and public space. Each type of space is demarcated with a specific distance, internally divided into a near phase and a far phase. The ‘portable territory’ mentioned above includes the intimate and personal spaces in this typology. According to Hall’s generalization, these portable territories end at four feet (1.2 meters), where social space begins. In his typology, ‘social space’ (See Diagram 01) spans between four to twelve feet, which is housed between personal and the public space. Edward T. Hall elaborates that “a proxemic feature of social distance is that it can be used to insulate or screen people from each other” (1966: 123). Social distance thus demarcates the end of physical dominion of an individual or, in other words, literally the jurisdiction of the portable territory.

Diagram 01: Distance Typology

In the case of COVID-19, hypothesizing that every person could be a possible carrier of the pathogen, one must maintain the one-metre distance. The distance of one-meter marks the outer boundary of the personal space and the inner boundary of the social space. An effective way to control the pathogens’ spread is to ensure that one strictly remains within one’s portable territory or, control people’s proxemic behaviour. This is very challenging since human beings have been civilized as social beings with defined and undefined social spaces!

Social distancing has become our new norm, and there is an undeniable need for this restriction. However, proxemic behaviour is not entirely an individual matter of concern. People of different cultures display different proxemic patterns; in other words, proxemic patterns are culturally highly conditioned. The concepts of ‘near’ and ‘distant’ are culturally different and relative. “The specific distance chosen (between two or more individuals) depends on the transaction, the relationship of the interacting individuals, how they feel and what they are doing… (Hall, 1969: 128). Human space requirements are generally influenced by his/her environment and surroundings and cultural norms. It is essential to understand the various elements in the immediate surroundings and the larger social context that contribute to our sense of spaces, distances, and relations. Implementers of social distancing may think that all people in a queue are potential carriers of the coronavirus, and therefore, one must maintain a distance of one meter. But some people may feel uncomfortable with social distancing simply because they may have socialized into different proxemic patterns.

Our proxemic behaviour may change, given the particular circumstances. For example, the need to feed a crying child at home, ailing parents, or one’s family overrides the fear of the virus, and the social distance is often contracted, in fear the person in front may grab what you may need. How people feel about each other at a particular time in a given space is a decisive factor in maintaining distance. In his study, Edward T. Hall explains that when people are angry and frustrated, they unknowingly tend to move closer. Some people often forget or become inconsiderate about maintaining social distance simply because of the urgency that being served in a regular queue entails. On such occasions, people are often characterized and labelled as irrational, undisciplined, and even unruly, whereas in political gatherings, opening ceremonies, personalized ‘bodhi pujas,’ etc., proxemic behaviour is often overlooked.

The standard proxemics required to control the COVID-19 pandemic are not realities for people who live in congested localities such as urban low-income areas and plantation areas where COVID-19 is fast spreading. Public services and commercial activities must be streamlined to facilitate a rational proxemic behaviour to maintain the social distance (see, for example, photograph no.1), with the understanding that the proxemic behaviour is culturally conditioned. It is very self-explanatory. Our discussion on proxemics here is not an argument against the requirement of one-meter restriction or any other form of social distancing. But understanding the cultural nuances of proxemics helps us be sensitive and intelligent when handling difficult situations rather than labelling people as irrational, undisciplined, and uncultured.

Few conclusive thoughts

What we have tried to emphasize in the article is the need and value of contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic geographically. There are two aspects to this. First, it is imperative that the prevalence of the COVID-19 is mapped at the GN level with the available data focusing on individual MOH divisions. With our ‘sample’ exercise of Kandy, we have shown that a better spatial picture can be derived from GN level mapping. Since the MOH division, among others, is a crucial operational spatial unit for matters of public health, it is essential to map the number of COVID-19 patients at the MOH level, preferably even randomly locating them within GN divisions. The unintended benefit of such mapping would be that the existing health record systems (IMMR/eIMMR, etc.) will be further developed as a spatial health record system. A spatial health record system helps to understand the ecological dynamics of any disease and can be used as a real-time health monitoring and surveillance tool. The existing health record systems contain patients’ identity numbers (bed-head ticket number), age, gender, postal address, etc. If locational information such as GN, DSD, and district can be added, the data can easily be extracted at any spatial unit from the database for analysis in a crisis. Moreover, the postal addresses can be converted to Geographic Coordinates, indicating the patients’ geographical locations, using geocoding techniques.

Second, it is essential to understand the socioeconomic and ecological contexts of areas where the disease spreads at high intensity. Such a task is made difficult because of the unavailability of data relating to socioeconomic contexts at the GN level. However, the existing administrative system and its resources (Divisional Secretaries, Grama NIladharis, etc.) can be utilized to gather information about local areas. The process of controlling the pandemic must be localized with the MOH as the key operational spatial unit while adhering to national health guidelines and ethical concerns. It is time for the MOH-led system to take pro-active measures (i.e., creating awareness), in collaboration with the existing administrative setup, community organizations and networks, to safeguard the areas where the disease has not yet spread. Most importantly, this process needs to be monitored at the district level. Perhaps, district task forces need to be established to assess and take stock of the district’s current situation, preferably at the GN division level, and implement management and preventive measures.

In its recommendations, the WHO has repeatedly emphasized the need to adhere to both public health and social measures and, very importantly, select and ‘calibrate based on their local context.’ The WHO writes very clearly in its ‘COVID-19 Global Risk Communication and Community Engagement Strategy,’ that “COVID-19 is more than a health crisis; it is also an information and socioeconomic crisis.” It highlights the need to be ‘informed by data that cover the community needs, issues, and perceptions’ and engage with the communities. When the pandemic becomes protracted and the vaccines are not within reach, it is crucial to engage with the communities at the lower levels to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authorities must pay special attention to the areas that it has not yet spread and take pro-active measures to safeguard those areas, perhaps with the assistance of community organizations and institutions to create awareness among communities.

It appears that people are becoming complacent, and this can exacerbate the situation. Generally, people expect the government to control the second wave and are less inclined to take responsibility for individual behaviours and public health and social measures. On the other hand, the government seems to expect the full responsibility to be taken by the individuals. As the pandemic situation is drawn out, people tend to take risks for granted and assumes normalcy. Such complacency can be detrimental to the process of controlling the pandemic. Such complacency is also a result of poor or lack of communication about the disease, specially among vulnerable communities. Although the Ministry of Health has developed a comprehensive set of health guidelines, whether they are effectively communicated to the people is a matter of concern. Many people cannot grasp the severity of the disease and the significance of adhering to preventive health and social measures. Therefore, authorities must seriously consider sharing the responsibility of controlling the pandemic with the communities.

Finally, while we encourage mapping as a tool that can facilitate better decision making, it is important to understand that maps, and even charts and diagrams, etc., can become ‘political technologies.’ Such political technologies can instil a sense of concern, fear, and anxiety among the decision-makers and the public. We see that the pandemic is fast politicized in Sri Lanka. Mapping and geo-visualization of COVID-19 should not be ruled out either in fear of exposure or political manipulation, as it may suggest how the pandemic needs to be acted upon effectively at the local level.

Dr. Nalani Hennayake teaches a range of Human Geography courses) and Dr. Kumudini Kumarihamy teaches GIS and Health at the Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya.

(Concluded)

Features

The heart-friendly health minister

by Dr Gotabhya Ranasinghe

Senior Consultant Cardiologist

National Hospital Sri Lanka

When we sought a meeting with Hon Dr. Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Health, he graciously cleared his busy schedule to accommodate us. Renowned for his attentive listening and deep understanding, Minister Pathirana is dedicated to advancing the health sector. His openness and transparency exemplify the qualities of an exemplary politician and minister.

Dr. Palitha Mahipala, the current Health Secretary, demonstrates both commendable enthusiasm and unwavering support. This combination of attributes makes him a highly compatible colleague for the esteemed Minister of Health.

Our discussion centered on a project that has been in the works for the past 30 years, one that no other minister had managed to advance.

Minister Pathirana, however, recognized the project’s significance and its potential to revolutionize care for heart patients.

The project involves the construction of a state-of-the-art facility at the premises of the National Hospital Colombo. The project’s location within the premises of the National Hospital underscores its importance and relevance to the healthcare infrastructure of the nation.

This facility will include a cardiology building and a tertiary care center, equipped with the latest technology to handle and treat all types of heart-related conditions and surgeries.

Securing funding was a major milestone for this initiative. Minister Pathirana successfully obtained approval for a $40 billion loan from the Asian Development Bank. With the funding in place, the foundation stone is scheduled to be laid in September this year, and construction will begin in January 2025.

This project guarantees a consistent and uninterrupted supply of stents and related medications for heart patients. As a result, patients will have timely access to essential medical supplies during their treatment and recovery. By securing these critical resources, the project aims to enhance patient outcomes, minimize treatment delays, and maintain the highest standards of cardiac care.

Upon its fruition, this monumental building will serve as a beacon of hope and healing, symbolizing the unwavering dedication to improving patient outcomes and fostering a healthier society.We anticipate a future marked by significant progress and positive outcomes in Sri Lanka’s cardiovascular treatment landscape within the foreseeable timeframe.

Features

A LOVING TRIBUTE TO JESUIT FR. ALOYSIUS PIERIS ON HIS 90th BIRTHDAY

by Fr. Emmanuel Fernando, OMI

Jesuit Fr. Aloysius Pieris (affectionately called Fr. Aloy) celebrated his 90th birthday on April 9, 2024 and I, as the editor of our Oblate Journal, THE MISSIONARY OBLATE had gone to press by that time. Immediately I decided to publish an article, appreciating the untiring selfless services he continues to offer for inter-Faith dialogue, the renewal of the Catholic Church, his concern for the poor and the suffering Sri Lankan masses and to me, the present writer.

It was in 1988, when I was appointed Director of the Oblate Scholastics at Ampitiya by the then Oblate Provincial Fr. Anselm Silva, that I came to know Fr. Aloy more closely. Knowing well his expertise in matters spiritual, theological, Indological and pastoral, and with the collaborative spirit of my companion-formators, our Oblate Scholastics were sent to Tulana, the Research and Encounter Centre, Kelaniya, of which he is the Founder-Director, for ‘exposure-programmes’ on matters spiritual, biblical, theological and pastoral. Some of these dimensions according to my view and that of my companion-formators, were not available at the National Seminary, Ampitiya.

Ever since that time, our Oblate formators/ accompaniers at the Oblate Scholasticate, Ampitiya , have continued to send our Oblate Scholastics to Tulana Centre for deepening their insights and convictions regarding matters needed to serve the people in today’s context. Fr. Aloy also had tried very enthusiastically with the Oblate team headed by Frs. Oswald Firth and Clement Waidyasekara to begin a Theologate, directed by the Religious Congregations in Sri Lanka, for the contextual formation/ accompaniment of their members. It should very well be a desired goal of the Leaders / Provincials of the Religious Congregations.

Besides being a formator/accompanier at the Oblate Scholasticate, I was entrusted also with the task of editing and publishing our Oblate journal, ‘The Missionary Oblate’. To maintain the quality of the journal I continue to depend on Fr. Aloy for his thought-provoking and stimulating articles on Biblical Spirituality, Biblical Theology and Ecclesiology. I am very grateful to him for his generous assistance. Of late, his writings on renewal of the Church, initiated by Pope St. John XX111 and continued by Pope Francis through the Synodal path, published in our Oblate journal, enable our readers to focus their attention also on the needed renewal in the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka. Fr. Aloy appreciated very much the Synodal path adopted by the Jesuit Pope Francis for the renewal of the Church, rooted very much on prayerful discernment. In my Religious and presbyteral life, Fr.Aloy continues to be my spiritual animator / guide and ongoing formator / acccompanier.

Fr. Aloysius Pieris, BA Hons (Lond), LPh (SHC, India), STL (PFT, Naples), PhD (SLU/VC), ThD (Tilburg), D.Ltt (KU), has been one of the eminent Asian theologians well recognized internationally and one who has lectured and held visiting chairs in many universities both in the West and in the East. Many members of Religious Congregations from Asian countries have benefited from his lectures and guidance in the East Asian Pastoral Institute (EAPI) in Manila, Philippines. He had been a Theologian consulted by the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences for many years. During his professorship at the Gregorian University in Rome, he was called to be a member of a special group of advisers on other religions consulted by Pope Paul VI.

Fr. Aloy is the author of more than 30 books and well over 500 Research Papers. Some of his books and articles have been translated and published in several countries. Among those books, one can find the following: 1) The Genesis of an Asian Theology of Liberation (An Autobiographical Excursus on the Art of Theologising in Asia, 2) An Asian Theology of Liberation, 3) Providential Timeliness of Vatican 11 (a long-overdue halt to a scandalous millennium, 4) Give Vatican 11 a chance, 5) Leadership in the Church, 6) Relishing our faith in working for justice (Themes for study and discussion), 7) A Message meant mainly, not exclusively for Jesuits (Background information necessary for helping Francis renew the Church), 8) Lent in Lanka (Reflections and Resolutions, 9) Love meets wisdom (A Christian Experience of Buddhism, 10) Fire and Water 11) God’s Reign for God’s poor, 12) Our Unhiddden Agenda (How we Jesuits work, pray and form our men). He is also the Editor of two journals, Vagdevi, Journal of Religious Reflection and Dialogue, New Series.

Fr. Aloy has a BA in Pali and Sanskrit from the University of London and a Ph.D in Buddhist Philosophy from the University of Sri Lankan, Vidyodaya Campus. On Nov. 23, 2019, he was awarded the prestigious honorary Doctorate of Literature (D.Litt) by the Chancellor of the University of Kelaniya, the Most Venerable Welamitiyawe Dharmakirthi Sri Kusala Dhamma Thera.

Fr. Aloy continues to be a promoter of Gospel values and virtues. Justice as a constitutive dimension of love and social concern for the downtrodden masses are very much noted in his life and work. He had very much appreciated the commitment of the late Fr. Joseph (Joe) Fernando, the National Director of the Social and Economic Centre (SEDEC) for the poor.

In Sri Lanka, a few religious Congregations – the Good Shepherd Sisters, the Christian Brothers, the Marist Brothers and the Oblates – have invited him to animate their members especially during their Provincial Congresses, Chapters and International Conferences. The mainline Christian Churches also have sought his advice and followed his seminars. I, for one, regret very much, that the Sri Lankan authorities of the Catholic Church –today’s Hierarchy—- have not sought Fr.

Aloy’s expertise for the renewal of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka and thus have not benefited from the immense store of wisdom and insight that he can offer to our local Church while the Sri Lankan bishops who governed the Catholic church in the immediate aftermath of the Second Vatican Council (Edmund Fernando OMI, Anthony de Saram, Leo Nanayakkara OSB, Frank Marcus Fernando, Paul Perera,) visited him and consulted him on many matters. Among the Tamil Bishops, Bishop Rayappu Joseph was keeping close contact with him and Bishop J. Deogupillai hosted him and his team visiting him after the horrible Black July massacre of Tamils.

Features

A fairy tale, success or debacle

Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement

By Gomi Senadhira

senadhiragomi@gmail.com

“You might tell fairy tales, but the progress of a country cannot be achieved through such narratives. A country cannot be developed by making false promises. The country moved backward because of the electoral promises made by political parties throughout time. We have witnessed that the ultimate result of this is the country becoming bankrupt. Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet.” – President Ranil Wickremesinghe, 2024 Budget speech

Any Sri Lankan would agree with the above words of President Wickremesinghe on the false promises our politicians and officials make and the fairy tales they narrate which bankrupted this country. So, to understand this, let’s look at one such fairy tale with lots of false promises; Ranil Wickremesinghe’s greatest achievement in the area of international trade and investment promotion during the Yahapalana period, Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (SLSFTA).

It is appropriate and timely to do it now as Finance Minister Wickremesinghe has just presented to parliament a bill on the National Policy on Economic Transformation which includes the establishment of an Office for International Trade and the Sri Lanka Institute of Economics and International Trade.

Was SLSFTA a “Cleverly negotiated Free Trade Agreement” as stated by the (former) Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Malik Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate on the SLSFTA in July 2018, or a colossal blunder covered up with lies, false promises, and fairy tales? After SLSFTA was signed there were a number of fairy tales published on this agreement by the Ministry of Development Strategies and International, Institute of Policy Studies, and others.

However, for this article, I would like to limit my comments to the speech by Minister Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate, and the two most important areas in the agreement which were covered up with lies, fairy tales, and false promises, namely: revenue loss for Sri Lanka and Investment from Singapore. On the other important area, “Waste products dumping” I do not want to comment here as I have written extensively on the issue.

1. The revenue loss

During the Parliamentary Debate in July 2018, Minister Samarawickrama stated “…. let me reiterate that this FTA with Singapore has been very cleverly negotiated by us…. The liberalisation programme under this FTA has been carefully designed to have the least impact on domestic industry and revenue collection. We have included all revenue sensitive items in the negative list of items which will not be subject to removal of tariff. Therefore, 97.8% revenue from Customs duty is protected. Our tariff liberalisation will take place over a period of 12-15 years! In fact, the revenue earned through tariffs on goods imported from Singapore last year was Rs. 35 billion.

The revenue loss for over the next 15 years due to the FTA is only Rs. 733 million– which when annualised, on average, is just Rs. 51 million. That is just 0.14% per year! So anyone who claims the Singapore FTA causes revenue loss to the Government cannot do basic arithmetic! Mr. Speaker, in conclusion, I call on my fellow members of this House – don’t mislead the public with baseless criticism that is not grounded in facts. Don’t look at petty politics and use these issues for your own political survival.”

I was surprised to read the minister’s speech because an article published in January 2018 in “The Straits Times“, based on information released by the Singaporean Negotiators stated, “…. With the FTA, tariff savings for Singapore exports are estimated to hit $10 million annually“.

As the annual tariff savings (that is the revenue loss for Sri Lanka) calculated by the Singaporean Negotiators, Singaporean $ 10 million (Sri Lankan rupees 1,200 million in 2018) was way above the rupees’ 733 million revenue loss for 15 years estimated by the Sri Lankan negotiators, it was clear to any observer that one of the parties to the agreement had not done the basic arithmetic!

Six years later, according to a report published by “The Morning” newspaper, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) on 7th May 2024, Mr Samarawickrama’s chief trade negotiator K.J. Weerasinghehad had admitted “…. that forecasted revenue loss for the Government of Sri Lanka through the Singapore FTA is Rs. 450 million in 2023 and Rs. 1.3 billion in 2024.”

If these numbers are correct, as tariff liberalisation under the SLSFTA has just started, we will pass Rs 2 billion very soon. Then, the question is how Sri Lanka’s trade negotiators made such a colossal blunder. Didn’t they do their basic arithmetic? If they didn’t know how to do basic arithmetic they should have at least done their basic readings. For example, the headline of the article published in The Straits Times in January 2018 was “Singapore, Sri Lanka sign FTA, annual savings of $10m expected”.

Anyway, as Sri Lanka’s chief negotiator reiterated at the COPF meeting that “…. since 99% of the tariffs in Singapore have zero rates of duty, Sri Lanka has agreed on 80% tariff liberalisation over a period of 15 years while expecting Singapore investments to address the imbalance in trade,” let’s turn towards investment.

Investment from Singapore

In July 2018, speaking during the Parliamentary Debate on the FTA this is what Minister Malik Samarawickrama stated on investment from Singapore, “Already, thanks to this FTA, in just the past two-and-a-half months since the agreement came into effect we have received a proposal from Singapore for investment amounting to $ 14.8 billion in an oil refinery for export of petroleum products. In addition, we have proposals for a steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million), sugar refinery ($ 200 million). This adds up to more than $ 16.05 billion in the pipeline on these projects alone.

And all of these projects will create thousands of more jobs for our people. In principle approval has already been granted by the BOI and the investors are awaiting the release of land the environmental approvals to commence the project.

I request the Opposition and those with vested interests to change their narrow-minded thinking and join us to develop our country. We must always look at what is best for the whole community, not just the few who may oppose. We owe it to our people to courageously take decisions that will change their lives for the better.”

According to the media report I quoted earlier, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) Chief Negotiator Weerasinghe has admitted that Sri Lanka was not happy with overall Singapore investments that have come in the past few years in return for the trade liberalisation under the Singapore-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement. He has added that between 2021 and 2023 the total investment from Singapore had been around $162 million!

What happened to those projects worth $16 billion negotiated, thanks to the SLSFTA, in just the two-and-a-half months after the agreement came into effect and approved by the BOI? I do not know about the steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million) and sugar refinery ($ 200 million).

However, story of the multibillion-dollar investment in the Petroleum Refinery unfolded in a manner that would qualify it as the best fairy tale with false promises presented by our politicians and the officials, prior to 2019 elections.

Though many Sri Lankans got to know, through the media which repeatedly highlighted a plethora of issues surrounding the project and the questionable credentials of the Singaporean investor, the construction work on the Mirrijiwela Oil Refinery along with the cement factory began on the24th of March 2019 with a bang and Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his ministers along with the foreign and local dignitaries laid the foundation stones.

That was few months before the 2019 Presidential elections. Inaugurating the construction work Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said the projects will create thousands of job opportunities in the area and surrounding districts.

The oil refinery, which was to be built over 200 acres of land, with the capacity to refine 200,000 barrels of crude oil per day, was to generate US$7 billion of exports and create 1,500 direct and 3,000 indirect jobs. The construction of the refinery was to be completed in 44 months. Four years later, in August 2023 the Cabinet of Ministers approved the proposal presented by President Ranil Wickremesinghe to cancel the agreement with the investors of the refinery as the project has not been implemented! Can they explain to the country how much money was wasted to produce that fairy tale?

It is obvious that the President, ministers, and officials had made huge blunders and had deliberately misled the public and the parliament on the revenue loss and potential investment from SLSFTA with fairy tales and false promises.

As the president himself said, a country cannot be developed by making false promises or with fairy tales and these false promises and fairy tales had bankrupted the country. “Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet”.

(The writer, a specialist and an activist on trade and development issues . )