Features

The Chay root

by Jennifer Moragoda

The whole of this island [Mannar] is low ground, exhibiting a mixture of shells and sand…the soil being hardly susceptible of any sort of culture and the water generally impregnated with salt… In the most wild and uncultivated part of the sandy tracts the best chaya root is produced.

(Simon Casie Chitty, 1834)

An Ideal Habitat

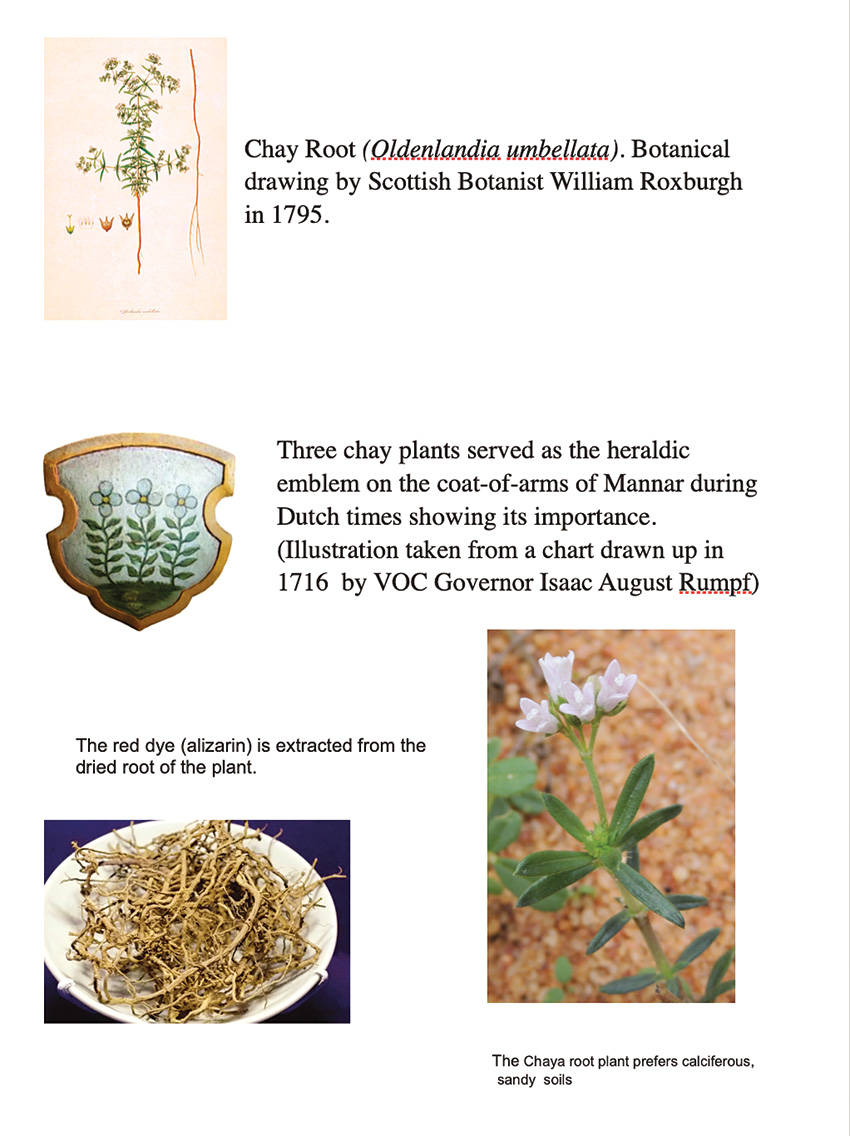

In the arid, inhospitable, saltine conditions of Mannar, few plants of commercial value thrive. Yet, in the past, one plant native to Mannar was an important commodity. Oldenlandia umbellata, which was known in Sri Lanka variously as chayaver, xaya, saya, say, chaya or chay, also grew in other parts of the island as well as in parts of coastal India. Chay was much in demand in fabric production centres, primarily on the Coromandel Coast of India — but also in the North of Sri Lanka. The lustrous and durable red it could produce was highly prized. In the hands of the most experienced and highly-skilled artisans, and in combination with other natural dyes and mordants, fine hand-printed cotton cloths with a rich palette of colour and intricate patterns were produced for export to markets throughout the world. This craft reached its zenith during the 17th-18th centuries. From early times, Mannar was an important centre for the collection and trade of this dyestuff. In fact, during Dutch times it even served as the heraldic emblem on the coat-of-arms of Mannar.

Chay is a low growing biennial herb, often somewhat woody and much branched, growing up to 30-50 cm tall. It has a very long yellow-red taproot, growing up to a length of 90 cm and small, pinkish-white flowers. The red colourant used in dyeing is obtained from the bark of the root. Oldenlandia umbellata contains alizarin as its sole colorant, which accounts for its dyeing superiority over other red-producing plants included in the Rubiaceae family which in the past were referred to generally (but less precisely) as Madder. In addition to its use as a dye, O. umbellata has been and continues to be used in traditional medicine in Sri Lanka (and in India and China) for the treatment of ailments including asthma and bronchitis.

Chay is said to thrive in soils rich in calcium. The calcium is absorbed by the root, and this in turn helps unleash its latent potential as it reacts with mordants used in the dyeing process to impart a durable and rich colour and fine lustre to cotton cloths. According to several sources, in its wild habitat the chay plant has shorter roots, yet yields one-fourth to one- third more colouring matter than when cultivated. The wild root was therefore preferred by dyers and mature two-year old plants were held to be the best.

Given their coral and shell-laden sandy soils, Mannar – and the Jaffna Islands of Karaitivu and Delft in particular – provided ideal habitats for chay. Dutch records state that chay from these areas was considered to be the best sources in Sri Lanka as these could impart a fine colour and lustrous finish to fabric. Chay growing in other parts of the North, while also used, did not yield such fine results. Henderick Becker, in his Memoir to Isaac Augustyn Rumpf dated 1718, stipulates that only the chay from Mannar, Delft, Karaitivu and Moelly(?) must be used in the “finer cloths…intended for the Fatherland and for Batavia” unless in cases of absolute necessity.

The Chay Rent & Diggers in Mannar

In Mannar, a group known as the Kadaiyars, carried out the digging, cleaning, drying and packing of the chay root. According to Markus Vink, the Kadaiyars were a Christian subdivision of the Pallars, a group who also lived along the Ramnad and Madurai Coasts of India. Casie Chitty stated that “according to traditions current among the natives, the island (Mannar) was in early times their (the Kadaiyars) hereditary property and exclusively occupied by them, subject to the king of Jaffna.” He also records that Totawelly (Toddavali) a small village three miles from Mannar town was “solely inhabited by that class of people who dig for chaya roots which abound in the neighbourhood”.

It is recorded that the Kadaiyars were “the poorest of all the inhabitants,” earning “meagre compensation for their labour,” barely earning enough income from their work to “derive a sustenance of dry rice,” and were obliged to work for the Dutch for eight months of the year in what was termed “uriyam” service. It is therefore understandable that, according to Dutch records, some chay root diggers tried to escape this obligation by fleeing to the Vanni.

The digging season in Mannar would commence in the month of January when the rains had subsided and continued until September. The rain helped to soften the soil, which was mostly a mixture of loamy earth and clay, making it easier to dig out the deep taproot. The diggers would usually start work in areas with these soils and end with the areas comprised of sandy ground. After harvesting, the root needed to be dried before use. If kept in a dark place, the efficacy of the chay root was said to rapidly deteriorate.

The practice of auctioning the right to collect and trade chay to private individuals known as the xaya rent was institutionalized by the Portuguese based on a tradition that had been followed in earlier times in the island. This practice, too, was followed by the Dutch in their turn, and then by the British. The monopoly was abandoned by the British and all taxes on the trade were abolished in 1831 as the demand for the dyestuff plummeted due to the introduction of cheap synthetic dyes to the market.

During Dutch rule Mannar was the principal centre for the collection and trade of chay root and a special department was established by them for the supervision of this work. Various measures were put in place to ensure a sufficient yield of the dye root. For example, lands where chay grew wild were not allowed to be ploughed for domesticated crops until the roots had been gathered, nor before the seeds of the chay plant had matured. And, on the northern side of the island, the roots were collected before the winds of the Southwest monsoon could bury them.

The Dutch relied for a large part of their chay from Mannar. In 1665, it was estimated that Mannar could produce more than 150,000 lbs. of chay root. However, at times the Dutch appear to have faced some challenges in obtaining enough quantities of the dye root to meet their fabric production requirements due to drought or the lack of manpower. Dutch Governor Baron van Imhoff stated in his memoir to his successor Willem Maurits Bruynink in 1740, that he raised the quantity to be supplied by the diggers by 30% for the next harvest.

Local Fabric Dyeing Using Chay Root

Casie Chitty wrote that Mannar was the principal town where the dyeing of cloths using chay root took place and that it was only practised in the Northern Province. Writing in 1834 he noted that there was a street in Mannar town known as “Painter Street” which was still occupied by persons of the dyeing caste. Later, in 1894, Trimens noted that this root was still being gathered “to a small extent” and “a village in Mannar is wholly occupied by a caste who dyes cloths with it”. We also know from the Dutch records that chay from Mannar was used in Jaffna for the dyeing of red cloths for export to Holland and Batavia.

Coomaraswamy1 writing in 1906 stated that chay was “one of the three plants most extensively used for dyeing in Ceylon,” the other two being jak (Artocarpus integrifolia) and patangi wood (Caesalpinia sappan). These latter two were used primarily in the dyeing of the robes of Buddhist monks and in rush and palm mats. He also stated that chay was the principal dyestuff used for the traditional heraldic and dewala flags produced in Jaffna for the Kandyan market.

A detailed description of the various methods, materials and tools used in the North for dyeing and printing fabrics using chay root left to us by S. Kantiseru in 1906 provides valuable information. We also have some European accounts from the 17th and 18th centuries of the dye methods used in the Coromandel factories which are interesting for comparison.

Key Steps in Traditional Chay-root Dyeing

In order to fix the red colour of chay onto cotton, the cloth needed to be treated in a tannic solution before being processed in the chay dye bath. Sources state that gallnut and aralu (Terminala chebula) were two tannins commonly used in Sri Lanka. To obtain a durable vibrant red, artisans boiled the cloths in a solution of chay root in three separate stages, each one at a progressively higher temperature. To obtain a dark red, alum was added to the dye bath. Kantiseru points out that sometimes short cuts were taken which resulted in an inferior colour which faded quickly.

To create outlines and highlights on the cloth, alum and iron were the principal mordants (karam) variously applied before dyeing in the chay solution. Alum in combination with iron was used to obtain black and purple, while a range of reds, from pink to scarlet and dark red could be obtained by applying a varying concentration of alum. A pen-like instrument (munkitturi) made from split bamboo with a ball of hair tied around the shaft acted as a reservoir for the mordant. The artisan regulated the flow of the latter by squeezing the reservoir. Beeswax as a resist was sometimes applied selectively to areas to prevent dye penetration during the different stages of the dyeing process. A tool which looked like a trident with a bar attached to the ends of each prong (kammiyattuuriakkal) was used to apply the wax to help create borders.

Post-script

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in natural dyes as a new more ecologically attuned generation recognizes their value over chemical dyes on environmental, health, and aesthetic grounds. Concurrently, scientific discoveries isolating the chemical properties of specific natural dyes and advances in technology have helped overcome some of the challenges and unpredictability of natural dyes. In India, scientists have been experimenting with chay, equipped with this new knowledge. Therefore, over 300 years after its international heyday, perhaps we have not seen the last of chay as a dyestuff.