Features

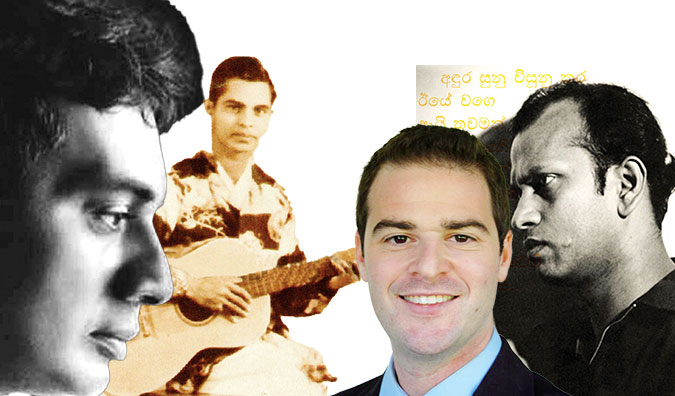

Some reflections on sinhala popular music

By Uditha Devapriya

In Modernizing Composition: Sinhala Song, Poetry, and Politics in Twentieth-Century Sri Lanka (University of California Press, 2017), Garrett Field emphasises the role that radio played in disseminating and elevating musical standards in the newly independent colonies of South Asia. The 1950s, when this process played itself out, was a period in which the state and institutional politics “became inextricable from linguistic nationalism.” Across Sri Lanka, these links found their fullest expression in Radio Ceylon, specifically after the latter began to employ professional Sinhala songwriters.

This was not a development unique to Sri Lanka. As Coonoor Kripalani has argued, in India radio served a pivotal function “in building patriotism and nationhood” after independence. Radio was cheaper and more accessible, while in Sri Lanka it predated television by three decades. In India, as in Sri Lanka, it provided litterateurs, composers, and performers who had depended on the patronage of the colonial bourgeoisie, and had thrived on the cultural revivalist movements of the 19th century, a more solid institutional footing.

Field’s book is important for several reasons, in particular its attempt at understanding the subtleties of Sinhala music through translation. However, it ends at a point – the mid-1960s – when Sinhala music was about to embark on its most colourful period.

To say this is not to belittle Field’s book. Modernizing Composition fills a great many gaps, including its exploration of the links between commercial capitalism and the revival of Sinhala music in the early 20th century. It also acknowledges that music and poetry cannot be viewed in isolation from one another, particularly in the context of newly decolonised societies searching for a cultural identity. Indeed, its immense scope and breadth are why Field’s analysis, sound as it is, should be carried forward to the 1960s and 1970s, especially since it was in these later periods that the factors that underpinned the popularity of Sinhala music – free education and linguistic nationalism – reached their apogees.

To be sure, these two periods – the 1940s-1950s and the 1960s-1970s – were qualitatively different. They imbibed different cultural influences and pandered to different audiences and markets. Following Sheldon Pollock, Professor Field uses the theory of “cosmopolitan vernacularism” to explain how, following independence, poets and songwriters grafted or superimposed classical literary aesthetics on regional languages and thereby gave birth to “new premodern vernacular literatures.” Throughout South Asia in general, and across Sri Lanka in particular, it was Sanskrit that indigenous poets and songwriters turned to in their quest to elevate their linguistic heritages and lineages. The more Westernised among them also sought inspiration from modernist American and European poetry.

Since I am by no means a specialist in anthropology, I cannot pass judgments on how these developments played themselves out in the 1960s. Yet it is clear that these developments had their origins in the period immediately preceding 1956. Now, 1956 meant a great many things to a great many people. To some it symbolised the triumph of the indigenous over the foreign; to others, the triumph of ethno-religious majoritarianism. Whichever way you look at it, 1956 provided the crucible through Sinhala music could continue to transform, to evolve, and to thrive. Here I am concerned with two musical forms: baila and pop music. My justification for this is simple: it is these two genres which facilitated the popularisation, or what I call the “middle-browing”, of Sinhala music after the 1960s.

Baila is more controversial and more contentious than Sinhala pop. As Anne Sheeran has noted, baila as a musical genre, activates both conformist and conservative elements. It at once provokes many of us to flout tradition, and compels not a few others to protest that flouting of tradition. Thus nationalist ideologues can bemoan the deterioration of cultural values, and parents can bemoan their children’s addition to the latest cultural trends, by invoking its name. In other words, is it the proverbial bogeyman in the room, a scapegoat for the death of culture, and the last resort of the puritan.

It is all these things. Yet as one historian communicated to me some years ago, baila stands with ves natum as one of the most uniquely indigenous cultural forms in Sri Lanka, an irony given their foreign roots (Portuguese and Indian). And in the 1960s and 1970s, it underwent a transition that would define the trajectory of Sinhala music.

The significance of this transition cannot be overrated. Such transitions were taking place in other cultural spheres as well. In literature, the renaissance that had been heralded by Martin Wickramasinghe had meandered to the popular fiction of Karunasena Jayalath. In film, Lester James Peries’s experiments had enabled a number of directors, including two of his assistants and colleagues, Titus Thotawatte (Chandiya) and Tissa Liyanasuriya (Saravita), to seek a middle-ground between artistic and commercial cinema. The situation was rather different in the theatre, where a new generation of bilingual writers, including Dayananda Gunawardena, Premaranjith Tilakaratne, G. D. L. Perera, Henry Jayasena, Dhamma Jagoda, Gunasena Galappatti, and Simon Navagattegama, continued to hold on to some semblance of a benchmark. Yet even they sought a break from the past.

By this I do not mean to say, or suggest, that there was a complete rupture in Sinhala music. The old musical forms continued to thrive, if not evolve. The first generation of lyricists and songwriters, including Chandraratne Manawasinghe, Madawala Rathnayake, and the great Mahagama Sekara, continued to write for old collaborators, as well as new voices. However, many of them remained utterly classical in their views on music, and it was these views that prevailed at Radio Ceylon. As Tissa Abeysekera has controversially remarked, on more than one occasion, this had the effect of stunting the growth of Western music in Sri Lanka, even as Western music was gaining popularity over the airwaves and on film in India. Against that backdrop, a new generation of composers was bound to emerge.

In a series of essays, all anthologised in Roots, Reflections and Reminiscences (Sarasavi, 2007), Abeysekera argues that the conflict here was between those who advocated the Indianisation or Sanskritisation of local music and those who promoted more vernacular, indigenous musical forms. He refers to the visit of S. N. Ratanjankar and the audition that was conducted at Radio Ceylon, under his supervision, and points out that these led to the stagnation of Sinhala music. However, Garrett Field’s take on the visit, and the audition, is different: citing a speech that he delivered at the Royal Asiatic Society in Colombo, a speech Abeysekara does not quote from, Field contends that Ratanjankar wanted artistes to “create a modern song, based on folk poetry and folk music.” This is at variance with Abeysekera’s reading of events, which make it out that Ratanjankar, if not the authorities at Radio Ceylon, marginalised proponents of folk music, including Sunil Shantha.

I think both Field and Abeysekera have a point, and both are correct. While promoting if not advocating the indigenisation of music, Sinhala composers consciously went back to North Indian influences. Contrary to what Abeysekera has written, what this achieved in the end was a fusion of disparate cultural elements – Sinhala folk poetry and Sanskrit aesthetics – which laid the groundwork for an efflorescence in Sinhala music. At the same time, those who diverged from the mainstream trend of incorporating North Indian musical elements retreated to a world of their own. They included not just Sunil Shantha, but also the first-generation proponents of baila, like Wally Bastiansz, who found a niche audience eager to listen to them but failed to penetrate more middle-class audiences.

The question thus soon arose as to who could push these developments on to mainstream listeners. In the 1950s Sinhala composers and lyricists had popularised folk poetry through sarala gee, or light classical songs. In the 1960s baila had succeeded folk poetry as a popular musical form. The task of making baila palatable for young, Sinhala speaking audiences, fell on a new generation of composers. This new generation found their inspiration not so much in North Indian music as in Elvis, the Beatles, and Jimi Hendrix.

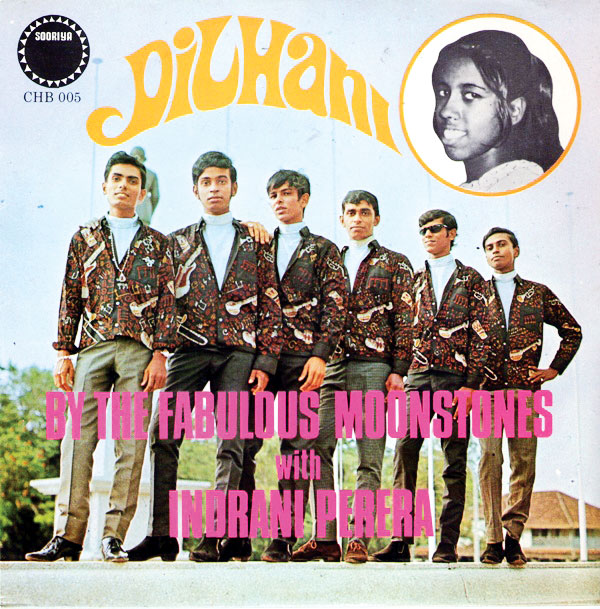

Their turning point, if it can be called that, came in 1967, a decade after 1956, when a little-known group, called The Moonstones, made their debut on Radio Ceylon. Featuring guitars, congas, maracas, and Cuban drums, their impact was immediate, so much so that within the next two years, both Phillips and Sooriya had signed them onboard.

What The Moonstones, and its lead Clarence Wijewardena, did was not so much challenge or flout the musical establishment of their time as to perform for an audience different in outlook and attitude to the audiences which the establishment had pandered to until then. This is a very important point, since I do not think there was a grand overarching conflict, in any way, between the new generation and the old. The old lyricists continued to write for their collaborators, and they willingly collaborated with the new voices: Sekara, for instance, wrote a song for one of the more prominent new voices, Indrani Perera, while Amaradeva sang for Clarence Wijewardena. Contrary to Abeysekera, I hence prefer to see this period as one of collaboration rather than outright, fight-to-the-death competition.

Field’s analysis, as I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, ends somewhere in the 1960s. His research is impeccably sound, and it deserves being carried forward. More than anything else, we need to know more about the audiences that the new composers, vocalists, and lyricists pandered to, and how exactly the latter groups pandered to them. We also need to know how their predecessors, who remained active in this period, interacted with them. I am specifically concerned here with the period from 1967 – when The Moonstones entered the mainstream – to 1978 – when a new government, a new economy, and an entirely new set of cultural forms and influences took the lead. All this represents much fieldwork for the anthropologist and historian of Sri Lankan, and South Asian, music. But it is the least we can do, given Garrett Field’s wonderful book and the many gaps it fills.

(The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.)

Features

The heart-friendly health minister

by Dr Gotabhya Ranasinghe

Senior Consultant Cardiologist

National Hospital Sri Lanka

When we sought a meeting with Hon Dr. Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Health, he graciously cleared his busy schedule to accommodate us. Renowned for his attentive listening and deep understanding, Minister Pathirana is dedicated to advancing the health sector. His openness and transparency exemplify the qualities of an exemplary politician and minister.

Dr. Palitha Mahipala, the current Health Secretary, demonstrates both commendable enthusiasm and unwavering support. This combination of attributes makes him a highly compatible colleague for the esteemed Minister of Health.

Our discussion centered on a project that has been in the works for the past 30 years, one that no other minister had managed to advance.

Minister Pathirana, however, recognized the project’s significance and its potential to revolutionize care for heart patients.

The project involves the construction of a state-of-the-art facility at the premises of the National Hospital Colombo. The project’s location within the premises of the National Hospital underscores its importance and relevance to the healthcare infrastructure of the nation.

This facility will include a cardiology building and a tertiary care center, equipped with the latest technology to handle and treat all types of heart-related conditions and surgeries.

Securing funding was a major milestone for this initiative. Minister Pathirana successfully obtained approval for a $40 billion loan from the Asian Development Bank. With the funding in place, the foundation stone is scheduled to be laid in September this year, and construction will begin in January 2025.

This project guarantees a consistent and uninterrupted supply of stents and related medications for heart patients. As a result, patients will have timely access to essential medical supplies during their treatment and recovery. By securing these critical resources, the project aims to enhance patient outcomes, minimize treatment delays, and maintain the highest standards of cardiac care.

Upon its fruition, this monumental building will serve as a beacon of hope and healing, symbolizing the unwavering dedication to improving patient outcomes and fostering a healthier society.We anticipate a future marked by significant progress and positive outcomes in Sri Lanka’s cardiovascular treatment landscape within the foreseeable timeframe.

Features

A LOVING TRIBUTE TO JESUIT FR. ALOYSIUS PIERIS ON HIS 90th BIRTHDAY

by Fr. Emmanuel Fernando, OMI

Jesuit Fr. Aloysius Pieris (affectionately called Fr. Aloy) celebrated his 90th birthday on April 9, 2024 and I, as the editor of our Oblate Journal, THE MISSIONARY OBLATE had gone to press by that time. Immediately I decided to publish an article, appreciating the untiring selfless services he continues to offer for inter-Faith dialogue, the renewal of the Catholic Church, his concern for the poor and the suffering Sri Lankan masses and to me, the present writer.

It was in 1988, when I was appointed Director of the Oblate Scholastics at Ampitiya by the then Oblate Provincial Fr. Anselm Silva, that I came to know Fr. Aloy more closely. Knowing well his expertise in matters spiritual, theological, Indological and pastoral, and with the collaborative spirit of my companion-formators, our Oblate Scholastics were sent to Tulana, the Research and Encounter Centre, Kelaniya, of which he is the Founder-Director, for ‘exposure-programmes’ on matters spiritual, biblical, theological and pastoral. Some of these dimensions according to my view and that of my companion-formators, were not available at the National Seminary, Ampitiya.

Ever since that time, our Oblate formators/ accompaniers at the Oblate Scholasticate, Ampitiya , have continued to send our Oblate Scholastics to Tulana Centre for deepening their insights and convictions regarding matters needed to serve the people in today’s context. Fr. Aloy also had tried very enthusiastically with the Oblate team headed by Frs. Oswald Firth and Clement Waidyasekara to begin a Theologate, directed by the Religious Congregations in Sri Lanka, for the contextual formation/ accompaniment of their members. It should very well be a desired goal of the Leaders / Provincials of the Religious Congregations.

Besides being a formator/accompanier at the Oblate Scholasticate, I was entrusted also with the task of editing and publishing our Oblate journal, ‘The Missionary Oblate’. To maintain the quality of the journal I continue to depend on Fr. Aloy for his thought-provoking and stimulating articles on Biblical Spirituality, Biblical Theology and Ecclesiology. I am very grateful to him for his generous assistance. Of late, his writings on renewal of the Church, initiated by Pope St. John XX111 and continued by Pope Francis through the Synodal path, published in our Oblate journal, enable our readers to focus their attention also on the needed renewal in the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka. Fr. Aloy appreciated very much the Synodal path adopted by the Jesuit Pope Francis for the renewal of the Church, rooted very much on prayerful discernment. In my Religious and presbyteral life, Fr.Aloy continues to be my spiritual animator / guide and ongoing formator / acccompanier.

Fr. Aloysius Pieris, BA Hons (Lond), LPh (SHC, India), STL (PFT, Naples), PhD (SLU/VC), ThD (Tilburg), D.Ltt (KU), has been one of the eminent Asian theologians well recognized internationally and one who has lectured and held visiting chairs in many universities both in the West and in the East. Many members of Religious Congregations from Asian countries have benefited from his lectures and guidance in the East Asian Pastoral Institute (EAPI) in Manila, Philippines. He had been a Theologian consulted by the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences for many years. During his professorship at the Gregorian University in Rome, he was called to be a member of a special group of advisers on other religions consulted by Pope Paul VI.

Fr. Aloy is the author of more than 30 books and well over 500 Research Papers. Some of his books and articles have been translated and published in several countries. Among those books, one can find the following: 1) The Genesis of an Asian Theology of Liberation (An Autobiographical Excursus on the Art of Theologising in Asia, 2) An Asian Theology of Liberation, 3) Providential Timeliness of Vatican 11 (a long-overdue halt to a scandalous millennium, 4) Give Vatican 11 a chance, 5) Leadership in the Church, 6) Relishing our faith in working for justice (Themes for study and discussion), 7) A Message meant mainly, not exclusively for Jesuits (Background information necessary for helping Francis renew the Church), 8) Lent in Lanka (Reflections and Resolutions, 9) Love meets wisdom (A Christian Experience of Buddhism, 10) Fire and Water 11) God’s Reign for God’s poor, 12) Our Unhiddden Agenda (How we Jesuits work, pray and form our men). He is also the Editor of two journals, Vagdevi, Journal of Religious Reflection and Dialogue, New Series.

Fr. Aloy has a BA in Pali and Sanskrit from the University of London and a Ph.D in Buddhist Philosophy from the University of Sri Lankan, Vidyodaya Campus. On Nov. 23, 2019, he was awarded the prestigious honorary Doctorate of Literature (D.Litt) by the Chancellor of the University of Kelaniya, the Most Venerable Welamitiyawe Dharmakirthi Sri Kusala Dhamma Thera.

Fr. Aloy continues to be a promoter of Gospel values and virtues. Justice as a constitutive dimension of love and social concern for the downtrodden masses are very much noted in his life and work. He had very much appreciated the commitment of the late Fr. Joseph (Joe) Fernando, the National Director of the Social and Economic Centre (SEDEC) for the poor.

In Sri Lanka, a few religious Congregations – the Good Shepherd Sisters, the Christian Brothers, the Marist Brothers and the Oblates – have invited him to animate their members especially during their Provincial Congresses, Chapters and International Conferences. The mainline Christian Churches also have sought his advice and followed his seminars. I, for one, regret very much, that the Sri Lankan authorities of the Catholic Church –today’s Hierarchy—- have not sought Fr.

Aloy’s expertise for the renewal of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka and thus have not benefited from the immense store of wisdom and insight that he can offer to our local Church while the Sri Lankan bishops who governed the Catholic church in the immediate aftermath of the Second Vatican Council (Edmund Fernando OMI, Anthony de Saram, Leo Nanayakkara OSB, Frank Marcus Fernando, Paul Perera,) visited him and consulted him on many matters. Among the Tamil Bishops, Bishop Rayappu Joseph was keeping close contact with him and Bishop J. Deogupillai hosted him and his team visiting him after the horrible Black July massacre of Tamils.

Features

A fairy tale, success or debacle

Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement

By Gomi Senadhira

senadhiragomi@gmail.com

“You might tell fairy tales, but the progress of a country cannot be achieved through such narratives. A country cannot be developed by making false promises. The country moved backward because of the electoral promises made by political parties throughout time. We have witnessed that the ultimate result of this is the country becoming bankrupt. Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet.” – President Ranil Wickremesinghe, 2024 Budget speech

Any Sri Lankan would agree with the above words of President Wickremesinghe on the false promises our politicians and officials make and the fairy tales they narrate which bankrupted this country. So, to understand this, let’s look at one such fairy tale with lots of false promises; Ranil Wickremesinghe’s greatest achievement in the area of international trade and investment promotion during the Yahapalana period, Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (SLSFTA).

It is appropriate and timely to do it now as Finance Minister Wickremesinghe has just presented to parliament a bill on the National Policy on Economic Transformation which includes the establishment of an Office for International Trade and the Sri Lanka Institute of Economics and International Trade.

Was SLSFTA a “Cleverly negotiated Free Trade Agreement” as stated by the (former) Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Malik Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate on the SLSFTA in July 2018, or a colossal blunder covered up with lies, false promises, and fairy tales? After SLSFTA was signed there were a number of fairy tales published on this agreement by the Ministry of Development Strategies and International, Institute of Policy Studies, and others.

However, for this article, I would like to limit my comments to the speech by Minister Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate, and the two most important areas in the agreement which were covered up with lies, fairy tales, and false promises, namely: revenue loss for Sri Lanka and Investment from Singapore. On the other important area, “Waste products dumping” I do not want to comment here as I have written extensively on the issue.

1. The revenue loss

During the Parliamentary Debate in July 2018, Minister Samarawickrama stated “…. let me reiterate that this FTA with Singapore has been very cleverly negotiated by us…. The liberalisation programme under this FTA has been carefully designed to have the least impact on domestic industry and revenue collection. We have included all revenue sensitive items in the negative list of items which will not be subject to removal of tariff. Therefore, 97.8% revenue from Customs duty is protected. Our tariff liberalisation will take place over a period of 12-15 years! In fact, the revenue earned through tariffs on goods imported from Singapore last year was Rs. 35 billion.

The revenue loss for over the next 15 years due to the FTA is only Rs. 733 million– which when annualised, on average, is just Rs. 51 million. That is just 0.14% per year! So anyone who claims the Singapore FTA causes revenue loss to the Government cannot do basic arithmetic! Mr. Speaker, in conclusion, I call on my fellow members of this House – don’t mislead the public with baseless criticism that is not grounded in facts. Don’t look at petty politics and use these issues for your own political survival.”

I was surprised to read the minister’s speech because an article published in January 2018 in “The Straits Times“, based on information released by the Singaporean Negotiators stated, “…. With the FTA, tariff savings for Singapore exports are estimated to hit $10 million annually“.

As the annual tariff savings (that is the revenue loss for Sri Lanka) calculated by the Singaporean Negotiators, Singaporean $ 10 million (Sri Lankan rupees 1,200 million in 2018) was way above the rupees’ 733 million revenue loss for 15 years estimated by the Sri Lankan negotiators, it was clear to any observer that one of the parties to the agreement had not done the basic arithmetic!

Six years later, according to a report published by “The Morning” newspaper, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) on 7th May 2024, Mr Samarawickrama’s chief trade negotiator K.J. Weerasinghehad had admitted “…. that forecasted revenue loss for the Government of Sri Lanka through the Singapore FTA is Rs. 450 million in 2023 and Rs. 1.3 billion in 2024.”

If these numbers are correct, as tariff liberalisation under the SLSFTA has just started, we will pass Rs 2 billion very soon. Then, the question is how Sri Lanka’s trade negotiators made such a colossal blunder. Didn’t they do their basic arithmetic? If they didn’t know how to do basic arithmetic they should have at least done their basic readings. For example, the headline of the article published in The Straits Times in January 2018 was “Singapore, Sri Lanka sign FTA, annual savings of $10m expected”.

Anyway, as Sri Lanka’s chief negotiator reiterated at the COPF meeting that “…. since 99% of the tariffs in Singapore have zero rates of duty, Sri Lanka has agreed on 80% tariff liberalisation over a period of 15 years while expecting Singapore investments to address the imbalance in trade,” let’s turn towards investment.

Investment from Singapore

In July 2018, speaking during the Parliamentary Debate on the FTA this is what Minister Malik Samarawickrama stated on investment from Singapore, “Already, thanks to this FTA, in just the past two-and-a-half months since the agreement came into effect we have received a proposal from Singapore for investment amounting to $ 14.8 billion in an oil refinery for export of petroleum products. In addition, we have proposals for a steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million), sugar refinery ($ 200 million). This adds up to more than $ 16.05 billion in the pipeline on these projects alone.

And all of these projects will create thousands of more jobs for our people. In principle approval has already been granted by the BOI and the investors are awaiting the release of land the environmental approvals to commence the project.

I request the Opposition and those with vested interests to change their narrow-minded thinking and join us to develop our country. We must always look at what is best for the whole community, not just the few who may oppose. We owe it to our people to courageously take decisions that will change their lives for the better.”

According to the media report I quoted earlier, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) Chief Negotiator Weerasinghe has admitted that Sri Lanka was not happy with overall Singapore investments that have come in the past few years in return for the trade liberalisation under the Singapore-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement. He has added that between 2021 and 2023 the total investment from Singapore had been around $162 million!

What happened to those projects worth $16 billion negotiated, thanks to the SLSFTA, in just the two-and-a-half months after the agreement came into effect and approved by the BOI? I do not know about the steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million) and sugar refinery ($ 200 million).

However, story of the multibillion-dollar investment in the Petroleum Refinery unfolded in a manner that would qualify it as the best fairy tale with false promises presented by our politicians and the officials, prior to 2019 elections.

Though many Sri Lankans got to know, through the media which repeatedly highlighted a plethora of issues surrounding the project and the questionable credentials of the Singaporean investor, the construction work on the Mirrijiwela Oil Refinery along with the cement factory began on the24th of March 2019 with a bang and Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his ministers along with the foreign and local dignitaries laid the foundation stones.

That was few months before the 2019 Presidential elections. Inaugurating the construction work Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said the projects will create thousands of job opportunities in the area and surrounding districts.

The oil refinery, which was to be built over 200 acres of land, with the capacity to refine 200,000 barrels of crude oil per day, was to generate US$7 billion of exports and create 1,500 direct and 3,000 indirect jobs. The construction of the refinery was to be completed in 44 months. Four years later, in August 2023 the Cabinet of Ministers approved the proposal presented by President Ranil Wickremesinghe to cancel the agreement with the investors of the refinery as the project has not been implemented! Can they explain to the country how much money was wasted to produce that fairy tale?

It is obvious that the President, ministers, and officials had made huge blunders and had deliberately misled the public and the parliament on the revenue loss and potential investment from SLSFTA with fairy tales and false promises.

As the president himself said, a country cannot be developed by making false promises or with fairy tales and these false promises and fairy tales had bankrupted the country. “Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet”.

(The writer, a specialist and an activist on trade and development issues . )