Midweek Review

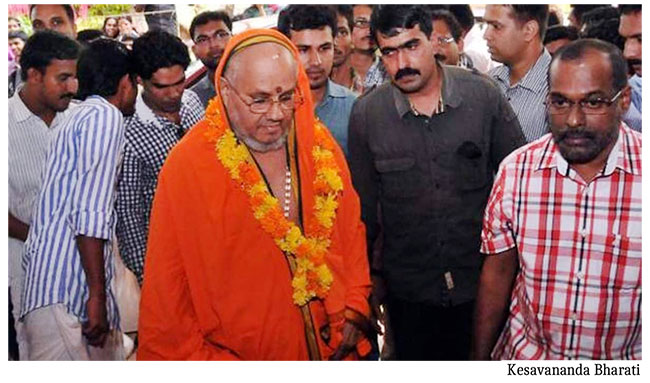

Significance of Kesavananda case to discussions on constitutional reform in SL

By Dharshan Weerasekera

The seminal Indian case, Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), has been called “The case that saved Indian democracy.” As such, it is of immense importance to Sri Lankan citizens because democracy in this country is also arguably very much in need of saving. Unfortunately, there has been very little discussion of this case in local academic journals, or newspapers, lately, and it is in the public interest to start one. Today, much of the discussion on constitutional reform is focused on whether or not to abolish the executive presidency.

However, common sense suggests that if one eliminates, or diminishes, the presidency, there might be a corresponding increase in the power of the legislature, which might lead to a different set of problems. I argue that, prior to suggesting specific amendments, such abolishing the presidency, or curtailing the powers of the office, Sri Lankan constitutional reformers should facilitate public discussions to help the people reach a consensus, as to the goal or goals—i.e. economic development, social justice, national unity, or any others—they wish to achieve through a new Constitution, or amendment of the present one.

The Kesavananda ruling has invaluable lessons to teach, in regard to the above matter. In this article, I shall briefly explain the facts, as well as the reasoning behind the judgment (ratio decidendi) of the case and discuss some of the lessons that Sri Lankan constitutional reformers can draw from the ruling, namely, a) the importance of having a clear sense of the underlying structure, or purpose, of the Constitution and b) the importance of post-enactment judicial review of legislation.

Facts of the case and ratio decidendi

The main issue that the court had to decide in this case was the extent of the Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution. Kesavananda Bharati, a Brahmin, was a resident of Kerala. In 1969, the state government implemented certain land reforms, ostensibly to help the poor acquire property. Meanwhile, in 1971 the Indian Parliament passed certain amendments to the Constitution intended to make the provisions of Part IV of the Indian Constitution which deals with “Directive Principles of State Policy” justiciable.

Directive principles are concerns or priorities that are intended to guide the state when formulating policy. Typically, they urge the state to advance social welfare, prevent the exploitation of the poor and so on. Under the Indian Constitution, as it was originally enacted in 1947, directive principles were not justiciable. However, as mentioned earlier, in 1971 the Indian Parliament amended the Constitution. It appeared that, the land reform measures of Kerala could be justified under these amendments.

In this background, Kesavananda challenged the land reform policy in question. He argued that, the policy, which was purportedly designed to uplift the condition of an entire group of people, clashed with his individual rights, which are protected under fundamental rights (Part III) of the Constitution. As mentioned, the main issue that the court had to decide was the extent of Parliament’s amending power. However, in order to answer that question, given the facts of the case, the court had to answer another question, namely, whether fundamental rights trumped directive principles or vice versa under the Indian Constitution.

Chief Justice S. M. Sikri, writing for the majority, ruled that the former was the case. His reasoning, as far as I understand it, is that the structure of the Constitution is designed to protect individual rights. To make directive principles which involve collective rights or benefits that apply to groups of people take precedence over fundamental rights would destroy the structure of the Constitution and thereby the Constitution itself.

He says, “We are unable to agree with the contention that in order to build a welfare state it is necessary to destroy some of the human freedoms. That, at any rate, is not the perspective of our Constitution. … Every encroachment on human freedoms sets a pattern for further encroachments. Our Constitutional plan is to eradicate poverty without destruction of individual freedoms.” (Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) 4 SCC 225, paragraph 705)

What the ruling teaches

There are two lessons, in particular, that Sri Lankans can draw from the Kasavananda ruling, a) the importance of having a clear idea of the underlying structure of the Constitution, and b) the importance of post-enactment judicial review of legislation. In order to explain the first, it is necessary to delve a little deeper into Justice Sikri’s argument regarding the vital role that the framers envisioned for fundamental rights in the Indian Constitution. The following two passages capture the essence of his argument.

In the first, he discusses the historical factors that influenced the framers. He says: “The objectives underlying our Constitution began to take shape as a result of forces that operated in the national struggle during the British rule where the British resorted to arbitrary acts of oppression such as brutal assaults on satyagrahis, internment, deportation, detention without trial and muzzling of the press. The harshness with which the executive operated its repressive measures strengthened the demand for Constitutional guarantees of fundamental rights.” (Kesavananda, paragraph 684)

In the second, he explains the social factors that must be taken into account when interpreting the Constitution. He says: “I must interpret Article 368 [Parliament’s amending power] in the setting of our Constitution, in the background of our history and in the light of our aspirations and hopes and other circumstances. No other Constitution in the world combines under its wings such diverse peoples, now numbering more than 550 million, with different languages and religions, and in different stages of economic development, into one nation, and no other nation is faced with such vast socio-economic problems.” (Kesavananda, paragraph 14)

In sum, the argument is that the purpose of the Indian Constitution is to forge a nation out of a population deeply divided by religious, linguistic, socio-economic and other such differences. Fundamental rights, being individual rights, are the one ingredient that gives all these people in spite of their differences a means to vindicate their rights under the Constitution. It is the means that creates equality among them and gives to each person a stake in the State. Therefore, to destroy it would destroy the Constitution and thereby also the nation.

The Kesavananda ruling is remarkable in that the court ruled against an arguably popular law at the time—since, who can conceivably object to measures to alleviate poverty. But, subsequent generations of Indians have lauded the ruling which means that the people consider that the court’s stance protected the long-term interests of the nation. So, the ruling has strengthened the Constitution and thereby the nation. Sri Lankan constitutional reformers should strive to set the stage for a similar evolution of a new Constitution or amendment of the present one.

I am not suggesting that Sri Lankans adopt the same purpose as the Indian Constitution, only that a clear conception of a purpose is needed. Without one, it would be very difficult for future generations of judges to interpret the Constitution.

Importance of post-enactment review of legislation

The second lesson that Kesavananda teaches is the importance of post-enactment review of legislation. Under the present Sri Lankan Constitution, post-enactment review is not possible. The only chance that citizens have for challenging legislation is at the Bill stage and that only for one week. Meanwhile, the fundamental rights chapter permits only challenges to executive and administrative actions. This is different from most other countries especially India and the U.S. where fundamental freedoms involve challenging legislative action.

In the final analysis, lack of a post-enactment review clause in the Constitution can be justified only if one presumes that judges are omniscient and can predict or discern all of the ways in which a particular law might affect members of the public in the future. However, common sense suggests that this is impossible. People begin to understand what a particular law entails only when it touches them in their day to day lives, that is, when the law is implemented. So, they must have a chance to challenge it at that point.

More importantly, when the court reviews a law in the above circumstances, the court is assessing the intention of the legislature at the particular time when it enacted the law in question against the court’s conception of the intention of the framers at the inception of the Constitution. So, the court is compelled to defend the Constitution in terms of whatever abiding principles it might have against the act of the legislature which, one must presume, is motivated by the more immediate exigencies or needs including public pressure faced by the lawmakers.

I am not suggesting that, the underlying principles of the Constitution as the court discerns them must always prevail in such an analysis. However, without the opportunity for the review, the principles themselves are never drawn out.

Conclusion

If Sri Lankans wish for a constitution that lasts, they must first reach a consensus on the purpose that they wish to achieve with the said Constitution, or amendment, of the present one. The other alternative is to leave successive governments to introduce amendments as and when they want. It is true that, such amendments, at the time they are introduced, might even be construed or defended as what the public also wants. However, reason and common sense not to mention historical experience suggest that this latter course might be a recipe for disaster.

(The author in an Attorney-at-Law)