Politics

Should Sri Lanka engage a LNG floating regassification vessel for electric power?

Part 3

What are the Health Safety Security and Environment (HSSE) requirements? What are the key insurance requirements?

What are the legal complexities and the means of resolving disputes?

What are the risks to the Sri Lankan Tax payer?

This Part 3 is largely in response to questions raised via email by readers of Parts 1 and 2.

Nalin Gunasekera

has spent 40 years in the offshore oil and gas industry with Royal Dutch/Shell, Mitsui and Mitsubishi, global leaders in leasing vessels and in the LNG business. His experience has been in Australia, NZ, South East Asia, PRC, West Africa and South America. The writer trained in Engineering in University of Ceylon and was a post graduate Colombo Plan scholar at University College London and is the recipient of Anniversary Technical Excellence Award from Shell for project recognised as a ‘market trend setter’.

What are the Health Safety Security and Environment (HSSE) requirements?

Safety and security are always major concerns to those unfamiliar with such installations.

Offshore installations such as FSRUs are regulated by various authorities who have jurisdiction over them. These are subjected to regulation and standardization by the coastal state GOSL, flag state, class (Classification Society), international and national standardization bodies and maritime regulators such as IMO, MARPOL, SOLAS and their regional directives. In view of the floating nature of the FSRU there are several parties involved, whose relationships should be clearly understood.

A Classification Society

is an independent, impartial, technical organization that establishes and administers standards, known as the Rules, for the design, construction and periodic survey of ships, offshore structures including floating systems and their facilities. Their principal concern is safety of the facilities and its personnel. Classification is the process of verifying compliance to their prescriptive Rules. It is often a prerequisite for obtaining insurance, fulfilling regulatory requirements or may be voluntarily elected as a means of demonstrating due diligence or as a component part of project quality assurance. Classification societies are empowered to act on behalf of national authorities in a number of aspects in most countries. This is because most countries do not have specific rules, design codes and standards specific for such specialised offshore installations. The FSRU will be classed by the likes of Lloyds, DNV-GL, ABS or Bureau Veritas.

It was noted during a presentation by the writer in about 2018 in Colombo that there are no items classified by Class Society that were then in operation in SL (as reported by the then Lloyds Register representative in SL). This reflects the poor adherence to international standards by the agencies of GOSL, by not mandating even basic industry practices.

A Flag State Authority

is the regulatory authority of the government of the state whose flag a vessel is entitled to fly. Flagging of the FSRU is not mandatory should the vessel not be in transit, however most countries that do not have codes and standards for offshore installations register the vessels in a port of registry. Usually, the vessel carrying a flag of convenience offers the vessel as collateral for financing purposes, which is an important factor in securing bids in a tender. The Flag State also prescribes safety measures. The term ‘’ describes the business practice of a in a country other than that of the ship’s owners, and flying that state’s on the ship. Ships may be registered under flags of convenience to reduce operating costs by avoiding regulations, inspection and scrutiny by the owner’s country. Normally the nationality (i.e. flag) of the ship determines the taxing jurisdiction. The Flag State has the and responsibility to enforce regulations over registered under its flag, including those relating to inspection, certification, and issuance of and prevention documents. As a ship operates under the laws of its flag state, these laws are applicable if the ship is involved in an such as maritime and nautical issues and disputes. This should be understood by agencies of GOSL.

Coastal State

is Sri Lanka. The regulatory authorities of GOSL exercise administrative control over the waters and seabed in which the FSRU is operating.

The relationships, requirements, and responsibilities between them are complex and not easily understood. This is because of (a) the number of regulatory authorities that may have jurisdiction on a particular project, (b) differences in scope and content of the regulatory systems in different countries (and to a lesser extent the Flag states) (c) the fact that few regulatory authorities have adopted their requirements to specifically address FSRUs.

In the writer’s experience, the scope and certification the classification society is empowered to perform are different for each flag and coastal state authority involved on a particular project as well as for different types of floating systems. Based on the writer’s experience in a number of countries, it is essential to identify and define, as early in the project as possible, all the relevant regulatory jurisdictions and requirements and to identify any unique technical and jurisdictional issues for early resolution with the Classification Society and the relevant regulatory authorities. The classification societies assist in defining these areas and resolving interpretations of relevant technical requirements, when engaged for this purpose, then report to all parties.

Gas leaks and subsequent explosions are not like oil leaks. Oil leaks pose relatively minor risks. Gas explosions engulf the entire region, when the flammable gas is under pressure. In a few seconds the explosion could destroy the entire infrastructure and the results are catastrophic. If the FSRU is to be located at the entry to the port, this could pose the threat of destruction to the entire ports’ activities. FSRUs are now typically located well away from port activities, and in open water.

The natural gas is to be piped from the FSRU via offshore and land pipelines meeting stringent oil and gas industry practice requirements. Installation of natural gas lines on land in populated areas raises safety issues with natural gas leaks being highly volatile and a high fire and explosion risk. They are usually subject to NIMBY (Not In My BackYard) protests and have led to project cancellations and delays. Now they are subject to BANANA (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anyone) constraints given the very high risk with gas lines, leading to catastrophic environmental disasters. The existing oil lines in the Colombo Port to Kolonnawa region are known to be poorly maintained, although leaking oil lines are exposed to a much lower level of risk. Proposals to run highly explosive natural gas lines in densely populated areas should expect louder protests than those during the Port City project. An option for GOSL to avoid high levels of risk in densely populated areas is to locate the FSRU in the vicinity of power generating plants in sparsely populated locations.

The fact that NFE would be responsible for the pipeline operation and maintenance (and not the GOSL/CEB) is a consolation given that NFE is concerned with their global reputation with their large operational portfolio where any failures would impact on their current and future broader business opportunities. Such operational records are closely monitored and reported by the industry and any failures will impact on insurance premiums as well, which concerns NFE. Sri Lanka has a poor duty of care record, an example being the emissions from coal-fired power generation which has led to mass protests.

ISPS (International Ship and Port Facility Security)

is a security measure put in place in response to the 9/11 attacks by the IMO (International Maritime Organization) as part of the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention. With the continuing threat of terrorism, the FSRU is expected to provide ISPS security provisions. In the writer’s experience, measures in excess of the standard provisions may be sought, which are project specific. The residual threats to Sri Lanka from the civil war that ended in 2009 should be noted. Regrettably, the nation continues to face terrorism threats, with the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings being a tragic example.

FSRU will have a high focus on the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process which is now mandatory for such projects. EIA is a process of evaluating the likely environmental impacts of a proposed project or development, considering inter-related socio-economic, cultural and human-health impacts, both beneficial and adverse.

An EIA will be carried out for the project as a tool used to identify the environmental, social and economic impacts prior to decision-making. This project has implications of the vessel being in the ocean in open water with a subsea pipeline as well as the pipeline on land via areas of high population density. Natural gas pipelines on land are always a concern and their operation and maintenance are covered by codes of practice such as by API and others. The EIA will identify the hazards and their mitigation of the complete installation, a risk analysis conducted, and methods of mitigation proposed. Today even the removal of the vessel is covered by EIA, in terms of what items are being left behind such as moorings and offshore structures.

The EIA to be carried out aims to predict environmental impacts at an early stage in project planning and design, find ways and means to reduce adverse impacts, shape the project to suit the local environment and present the predictions and options to decision-makers. By using EIA both environmental and economic benefits are achieved, such as reduced cost and time of project implementation and design, avoiding post project execution costs and in defining all the statutory consents required. The EIA reviews all hazards and their mitigation, assess and evaluate the impacts of the project and report the EIA including an Environment Management Plan and a non-technical summary for the general audience for public feedback and raise any concerns to be aired and resolved. The EIA should indicate whether the FSRU could provide the emergency response on a ‘stand-alone’ basis or with the support of facilities of SLPA or any other GOSL authority.

Safety systems continue to evolve as oil and gas operations become more challenging and they predominantly operate in a regime where the systems must meet requirements of prescribed standards. However, the legacy standards may not meet the requirements of highly complex industrial or technical systems such as offshore oil and gas installations in highly explosive environments where consequences of an accident can be catastrophic.

Thus, Safety Case is now being mandated by statutory authorities. Given the complexity of these operations most similar installations prescribe a Safety Case for these FSRUs. Major oil companies have mandated a Safety Case for all such installations since about 1995, which emerged from the Piper Alpha incident in 1988 with 167 fatalities. The writer has mandated a Safety Case for all the writer’s installations since about 2005. There have not been any reports of incidents where the facilities operated under a Safety Case regime. It is noteworthy that where major incidents with catastrophic events occurred, the facilities were not operating under a Safety Case regime, such as the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

A safety case is a document produced by the operator of a facility which:

Identifies the hazards and risks

Describes how the risks are managed and controlled

Describes the safety management system in place to ensure that controls are effectively and consistently applied.

Safety cases must be produced by the operator of an installation such as NFE. The principle here is that those who create the risk must manage it. It is the operators’ job to assess their processes, procedures, and systems to identify and evaluate risks and implement the appropriate controls, because the operator has the greatest in-depth knowledge of their installation. The Safety Case must identify the safety critical aspects of the facility, both technical and managerial. Analysis of disasters almost always show a combination of technical and managerial flaws which have led to the event occurring.

This is an excellent opportunity for countries such as Sri Lanka to be exposed to global HSSE practices rather than be lagging behind having no duty of care as evidenced in recent events. The writer’s insistence in mandating a Safety Case in the region has been appreciated long after the writer’s departure having an incident free record in their operations.

Notably an EIA was issued by Sojitz (Sojitz ref project 0443480) based on their proposal for an FSRU dated 21 Aug 2019, for public comment. Extensive comments were issued by the writer to GOSL, having been responsible for similar EIAs in New Zealand, Australia, Indonesia and Thailand. The comments were ignored by GOSL which appears to be a total lack of very basic duty of care to the public at large, which is a serious concern in exposing these high risk complex projects to the oversight of the GOSL representatives today. Such disregard by the government sets a dangerous precedent when GOSL’s agencies such as CEB is clamouring to undertake such complex projects, unaware of even the basics of this industry.

What are the key insurance requirements?

There are a host of insurance requirements, the key items being the following.

The installation will require to procure Protection and Indemnity insurance, more commonly known as P&I insurance, this is a form of mutual maritime insurance provided by a P&I Club. Whereas a company provides “hull and machinery” cover for shipowners, and cargo cover for cargo owners, a P&I Club provides cover for open-ended risks that traditional insurers are reluctant to insure. They are backed by a group of reinsurers who spread the risk. Typical P&I cover includes: a carrier’s third-party risks for damage caused to cargo during carriage; war risks; and risks of environmental damage such as oil spills and pollution and damages by any catastrophic event due to any explosion. P&I insurance for these offshore floating installations are now mandatory, which typically exceed about USD 400 mil. P&I insurance has been a serious omission in the recent CEB tenders. The importance of P&I insurance should be known after the recent X-Press Pearl disaster, a Singapore-flagged container ship that caught fire and sank north of Colombo, causing extensive environmental damage. The P&I insurance will indemnify and include wreck and debris removal and a pollution liability in respect of the FSRU.

The replacement value of the vessel will be covered under marine hull and machinery insurance.

There are occasions when Business Interruption insurance must be procured when (a) the performance of certain items in the facility cannot be guaranteed for the duration of the contract when only warranties apply (b) as a form of relaxing the terms of payment guarantees, and (c) as required by the bankers to guarantee their revenue stream.

Disproportionately high demobilisation and removal costs (often in excess of USD 50 million) are being incurred globally with these moored floating systems . Statutory authorities are planning to introduce trailing liabilities to hold previous owners liable for decommissioning costs if they sold ageing assets to new owners that lacked the financial and technical capacity to decommission the facilities. Such incidents have taken place where the taxpayer has to fund such expenses running into more than USD 100 million. Some form of insurance to cover such eventualities is now being proposed. The best example is in Australia where the removal cost has exceeded USD 200 million paid for by the tax payer in removing the vessel. See Northern Endeavour debacle hits $209M with much more to come

The insurance is procured via brokers to whom the attributes as such as Safety Case will be given credit to lower the premiums, given the lower risk exposure from the extensive analysis and the precautionary measures taken. Naturally the lower insurance premiums would be reflected in lower electricity prices.

The EIA will give an estimate of the above scope for P&I cover and the scope of the emergency response required. The EIA should indicate whether the FSRU could provide the emergency response on a ‘stand-alone’ basis or with the support of facilities of SLPA or any other GOSL authority. Often regional facilities available are considered when determining the emergency response, such as from India. It is hoped that minimum standards of insurance be covered in these projects as practiced elsewhere with the minimum cover stipulated, without burdening the taxpayer. The buck stops with the insurance companies.

What are the legal complexities and the means of resolving disputes?

These vessels operate typically under multiple jurisdictions some of which overlap, which are notoriously complex to understand. It is necessary to check Sri Lanka’s cabotage policy of permitting foreign flagged vessels operating in Sri Lanka’s waters. The FSRU will be foreign flagged as explained under HSSE above and offered as collateral to banks. The cabotage policy governs the operation of vessels between two places along coastal routes in the same country by a transport operator from another country, practised by many nations worldwide including developed nations. For some of these nations, it is so strictly implemented that no foreign-flagged vessels are even allowed to operate within their domestic waters for long periods. Obtaining waiver in some cases have involved seeking parliamentary approval in the host country should there be no precedent. In the writer’s experience the powerful maritime lobbies of host countries prevent foreign flagged vessels from operating in their waters and the employment of expatriate foreign personnel, in the operation of the FSRU. These may cause delays should there be no such precedent; the writer has faced such challenges elsewhere.

The vessel will be under the jurisdiction of the port of registry of a flag of convenience such as Liberia and Panama. Marshall Islands is becoming popular as a flag of convenience as explained under HSSE. As a ship operates under the laws of its flag state, their laws are applicable if the ship is involved in an such as maritime and nautical issues and disputes. Admiralty law or maritime law is a body of that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. This should be understood by GOSL, who has limited jurisdiction.

The governing law of the contract for the lease and supply of LNG and export of natural gas would not be based on laws of Sri Lanka. This is because these companies, banks and financiers who participate, do not have the time and resources to scrutinise Sri Lanka’s laws and usually laws of Sri Lanka do not apply to such contracts. Applicable laws familiar to the lawyers from these companies and banks such as the laws of UK, New York or Singapore are common in these transactions which have been proven over the years offering a good balance between the parties involved in transactions.

Usually, the expectation is that these disputes are eventually settled by arbitration outside the host country such as in London, via London Maritime Arbitrators Association. Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) is becoming increasingly popular for disputes arising from leased FSRU type vessels. Singapore has well trained lawyers involved in drafting these contracts known to the writer. Several cases have been assigned to SIAC since these vessels are also typically converted in Singapore shipyards and Singapore’s banks are also involved in syndicate financing. A record of present case studies are available to settle disputes. Several banks who provide equity finance and debt finance for these projects in the region are in Singapore and their disputes have been settled via SIAC.

What are the risks to the Sri Lankan Tax payer including the ‘end-of-life-burden’?

One of the great risks from CEB’s tender is in separating the FSRU contractor from the pipeline contractor. Unforeseen delays with pipeline installations are common. Offshore installations rarely run-on schedule, with some being delayed by six months or more being extremely sensitive to weather downtime in Sri Lanka, which is subject to monsoons. Further delays in laying gas pipelines across high density populated areas are extremely likely with land acquisition issues, environmental protests by politicians and the public. Usually, FSRUs are delivered on time, within 22 months, with similar conversions gained over more than 100 conversions in Singapore, where the writer has worked since 1994. FSRU suppliers wish to have their revenue stream early from the date of award of contract and would impose liquidated damages for any delay in pipeline delivery, whilst unable to supply regassified LNG. This could be of the order of USD 150,000 to 200,000/day for six months coming from the taxpayer’s account.

Usually the installation of FSRU and the offshore pipeline would be undertaken by the same contractor, which would not be the case with separate contractors as with CEB’s tender. These mobilisations/demobilisations could be of the order of USD 10 mil, which could have been saved, if performed by the same contactor as proposed by NFE.

The above are the advantages of a single point responsibility as proposed by NFE versus CEB’s attempt to separate the tenders where CEB would be responsible for the interface, with CEB lacking any exposure, inter alia, to any form of offshore oil and gas industry standards, codes, practices, industry norms, risks, Classification Society rules, insurance

requirements, offshore health, safety, security, and environmental practices.

There has been a trend to contract an overall tolling rate where payment is on the basis of LNG regassified and is expressed as $/mmbtu (million BTU). However, the actual rate will be dependent on the terminal utilisation (load factor). The utilisation cannot be determined accurately without carrying out detailed met ocean studies which should be (a) acceptable to a Classification Society and (b) acceptable to by Insurance companies. Usually utilisation could be of the order of 50%, which would double the actual rate. QED Consulting quotes estimated tolling rates (tariffs) in the range $0.60-0.94/mmbtu based on a 50% load factor. The contract with Excelerate for the Puerto Rico FSRU Aguirre terminal states $0.47/mmbtu. The rate for the first Bangladesh terminal is also stated to be $0.47/mmbtu. For the second Bangladesh terminal $0.45 has been stated. Assuming a 50% load factor the actual rates will again be around $1/mmbtu. The above rates are based on studies carried out by Oxford Institute of Energy Studies.

CEB lacking any exposure to highly specialised offshore oil and gas business and taking responsibility for the complex contractual and technical interface between the pipeline and FSRU would be a monumental disaster in the making. NFE poses no such interface risks with a single point responsibility for the whole project.

The removal costs of the FSRU could be of the order of USD 50 million as a minimum, could even well exceed USD 200 million, which is a significant ‘end-of-life-burden’ to the taxpayer. Its mitigation via insurance and relevant contractual obligations are noted above.

FSRUs are generally leased for longer periods than 10 years proposed by CEB for the vessel, examples being Lumpung Indonesia 20 years, Grace Columbia 20 years, Bahrain FSU 20 years, Armada Mediterrana Malta 18 years, Punta-de-Sayag, Uruguay 20 years, Port Qasim-3, Pakistan 20+5+5 years. Amortising the vessel in 10 years incurs a higher lease rate for the vessel depreciated over a shorter term, incurring a higher charge to GOSL. The short lease period exposes a lower period of depreciation of the vessel for amortisation with a higher lease rate, with a higher cost of electricity payable by the taxpayer.

CEB’s tender has omitted both Bureau Veritas who has classed 17 FSRUs worldwide and ABS and included only Lloyds and DNV. Such omission could cost the taxpayer in change of class of a vessel when converting a candidate vessel and reflects preferential treatment in a open tender.

It is questionable whether GOSL/CEB would be in a position to ‘take over’ the FSRU operations, for which a highly specialised skills set is required and a competency audit in the form of due diligence to secure P&I insurance.

Typically, these FSRU projects are leased, operated and removed by the vessel owner, particularly in countries such as Sri Lanka, which is incapable of running even a very basic coal generation plant without interruption. Sri Lanka could well be left with an inoperable facility of negative value such as the Urea Fertiliser Plant which was sold as scrap soon after start up. FSRU is cutting edge technology. GOSL is taking unnecessary risks in placing CEB to undertake this project, unlike NFE taking responsibility for the entire project. NFE has inherited the portfolio of the previous owner GOLAR who pioneered this industry in 2009, it comes with a wealth of experience.

The Urea Fertiliser Project was a multibillion rupee project which was sold as scrap soon after starting. Ronnie de Mel, then Minister of Finance and Planning, said in an address to Parliament on 21 December 1977: “We propose to introduce legislation very soon to make chairmen and directors of corporations personally liable for their actions in those corporations. They will make it a point to study their projects a little more carefully when they know that they will be personally held liable and that they will be charged and surcharged for any losses or lapses on their part.”

Features

Old Bottles, Spent Wine

By Uditha Devapriya

With elections coming up in a few months’ time – notwithstanding Palitha Range Bandara’s outrageous remarks, to which Saliya Pieris, the former President of the Bar Association, responded thoughtfully – new coalitions and alliances are cropping up. These have pulled together the unlikeliest MPs and ideologues, who you’d never put together in the same room but who have, in the aftermath of the 2022 crisis, have unified around certain issues. Outside of the government, the consensus seems to be that we have yet to see a proper Opposition. This is the selling promise of these new coalitions: they tout themselves as that proper Opposition, the only political groups that matter.

With elections coming up in a few months’ time – notwithstanding Palitha Range Bandara’s outrageous remarks, to which Saliya Pieris, the former President of the Bar Association, responded thoughtfully – new coalitions and alliances are cropping up. These have pulled together the unlikeliest MPs and ideologues, who you’d never put together in the same room but who have, in the aftermath of the 2022 crisis, have unified around certain issues. Outside of the government, the consensus seems to be that we have yet to see a proper Opposition. This is the selling promise of these new coalitions: they tout themselves as that proper Opposition, the only political groups that matter.

The most recent of these coalitions is the Sarvajana Balaya. Led by Dilith Jayaweera, it houses a galaxy of parties, representing diverse, often disparate, interests, including Wimal Weerawansa’s National Freedom Front, Udaya Gammanpila’s Pivithuru Hela Urumaya, the Democratic Left Front, the Communist Front, and a breakaway faction from the SLPP and government called the Independent MPs’ forum. There are other groups as well, and other personalities, including attorneys and former Chief Justices. They have colourful pasts, and they have given the new formation a very colourful platform.

Rhetoric and political statements aside, however, the Sarvajana Balaya is essentially a gathering of ex-Gotabaya Rajapaksa ideologues. Many of them, like Weerawansa and Gammanpila, resigned early on from the Rajapaksa administration, before the crisis in 2022. Others, like Gevindu Cumaratunga and Channa Jayasumana, broke ranks with that regime during the crisis. The Communist Party went beyond these formations by calling for reforms and directly taking part in the aragalaya at Galle Face. When goons attached to Mahinda Rajapaksa attacked Gotagogama in May, the CPSL’s chairman, Dr G. Weerasinghe, convened a press conference condemning Rajapaksa and asking him to resign.

Dilith Jayaweera is, of course, the ultimate ex-Rajapaksist, perhaps in the same way Ignazio Silone and Whittaker Chambers were the ultimate ex-Stalinists. When the government announced 10 plus hour power-cuts and hastily imposed a curfew after the confrontation at Mirihana on March 31, Jayaweera tussled with Namal Rajapaksa on Twitter. This led to perhaps the most significant political breach for the Rajapaksa government, since Jayaweera had, since at least 2018, spearheaded Gotabaya’s campaign from the sidelines. That he has refused to come full circle, and remains critical of Rajapaksa, is intriguing. At one level, one could call him sincerer than the SLPP, three-quarters of which slung mud at the UNP in 2019 but are now content being at its beck and call every day.

Jayaweera’s party, the Mawbima Janatha Pakshaya, is an enigma. It pontificates on the need for an alternative politics. It is high on protecting national assets, and straddles between transforming Sri Lanka “into a state of unparalleled dynamism” and “drawing inspiration from our rich culture and values rooted in our ancient civilisation.” At one level, its ideology bears analogies with the East Asian brand of developmentalist nationalism.

This is not to say Jayaweera is a Mahathir in the making, though I think he is more deserving of such epithets than Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who evoked comparisons with Vladimir Putin. In any case, kingmakers are deal-clinchers. Jayaweera’s party has the money and outreach, and is tapping into both. Against that backdrop, it makes sense for the party to enter agreements and pacts with other parties. In that regard, the Sarvajana Balaya has reached a consensus with two formations: the Old Left and the ex-Rajapaksa nationalists. For the Old Left, this marks a return to form. Last year, it spoke loftily about carving a different political space, but it has now reverted to its age-old strategy of aligning with nationalist forces. Since at least 1970, that seems to have been their preferred path to socialism.

I am being harsh on the Communist Party. But I am also being fair. Such strategies once had a purpose and logic. The geopolitics of the Cold War being what they were, the Left could make a cogent case for joining Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s coalition. The Left could make as cogent a case against it, but that’s another story. The point is that Bandaranaike represented a wave of anti-imperialist socialist leaders in the Third World, who the Left thought could be nurtured and pushed towards the Left. In this, however, the Left both overestimated and undermined the force of nationalism: it believed that nationalism would eventually wither away in the face of socialism, and saw nothing wrong in compromising on its animus against petty bourgeois ideologies if they could help foment a revolution.

The great lesson of the 1960s and 1970s, not just in Sri Lanka, but also in India, Algeria, and Egypt, was that nationalism could never lay the groundwork for a socialist society. It could only overtake it. The two, put simply, could never become one: there were just too many incompatibilities and incongruences. To give perhaps the best example, when Sirimavo Bandaranaike forced the LSSP and Communist Party out of her coalition, she shored up the right-wing of the SLFP, the Felix Dias flank. And when her brand of nepotism became too strong for even her MPs, the country witnessed a mass defection to the UNP, leading from an internal shift to the right (the SLFP) to an external, and far more consequential, shift to the right (from the Senanayake to the Jayewardene chapter in the UNP).

Yet, even with all this, it was possible to justify the Left’s forays into nationalist territory. As Vinod Moonesinghe has noted in a rebuttal to Nathan Sivasambu, not even the Left could ignore the electorate and the reality of “bourgeois democracy”, which had been granted to Sri Lanka long before other colonies and territories. 1956 marked a crucial turnaround in electoral politics. It led to the bifurcation of the Sinhala Buddhist right between the SLFP and the UNP. The choice for the Left seemed hard to make here, and for a while, controversial as it was, the LSSP and CPSL joined the the SLFP. That they soon embraced, almost uncritically, the SLFP’s descent into chauvinism (“Dudleyge badey masala vadai) is certainly unfortunate, even deplorable. But politically, it was felt necessary.

Half a century on, has the Old Left revamped its strategies? From its press conferences last year, one would have assumed so. At one point there was even speculation that the Old Left and New Left – the NPP – would band together, doing away with decades of sectarianism. This, however, was not meant to be. Instead, the Communist Party and the Democratic Left Front seem to have preferred joining Jayaweera, perhaps seeing the likes of Weerawansa, Gammanpila, and Cumaratunga as comrades who will lead them to that kalunika of Sinhala politics, the congruence of nationalism and developmentalism.

This is, of course, a mirage. But it underlies a tectonic shift in local politics.

Over the last few decades, we have seen a diminution of the Old Left and, ironically, the Mahinda Rajapaksist brand of nationalism. I have contended in my articles on Jathika Chintanaya that this reflects a broader shift within Sinhala Buddhist nationalism itself. The history of the Republican Party, some would say, boils down to the descent from Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump. Likewise, the history of Sinhala nationalism has been the descent from Gunadasa Amarasekara and Nalin de Silva to the hundred or so dilettantes who claim to be their descendants but are anything but. In that scheme, the likes of Weerawansa and Gammanpila have become the proverbial last of the lot, spouting a nationalist discourse which has become predictable and passé.

Why passé? Because Gotabaya Rajapaksa, promoted as the security-sovereignty candidate, facilitated the conjunction of nationalist and neoliberal forces. This dislodged the more populist sections of the nationalist camp – which Weerawansa epitomised – empowering a political class that wields nationalist, even communalist, rhetoric within a neoliberalised economic and social space. That could of course not have been possible without the Ranil Wickremesinghe presidency, but it would not have come to pass without his predecessor’s catastrophic failures. And no matter what Gotabaya may think, it was not, as the title of his book would have us believe, a conspiracy. It was stark, clear, obvious, from day one. Neither he nor his advisors can deny their culpability there.

Jayaweera’s developmentalist-nationalist vision shares more with the paternalistic right than the democratic left, notwithstanding his embracing a party which calls itself the Democratic Left Front. What is ironic is how ideologues attached to the Communist Party see it fit to attack the NPP, but see nothing wrong in joining forces with nationalist formations that have run their course and have given way to the most nefarious political conjuncture in Sri Lanka’s post-independence history: the SLPP-UNP pact. These parties are as complicit in that conjuncture as the parties that are in power. Not all the rosy words or mea culpas in the world can absolve them, or their accomplices, of this.

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher, and analyst based in Sri Lanka who contributes to a number of publications on topics such as history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy. He can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Quo Vadis?

1: Feeding the 225

2: Don’t wait for the state; let’s act on our own

by Kumar David

This has been the most rainy and squally Vesak that I can recall in my eight decades on this planet and it has made me grumpy. The depression in the Bay of Bengal has prepared all of for the couch of some psycho-quack conning folks with fictious talk of depressions.

This essay is in two separate parts unconnected with each other; a) Feeding the 225 and b) people taking the initiative into their hands and not relying on the state.

Feeding the 225

Jesus fed 5,000 with two fishes and five loaves (Mathew 14:13-21) and you may reckon that to be a great achievement but he did it only once. Our people in Sri Lanka have to keep feeding the 225 day-in-day-out every day of their lives. And where does it all go? Into political pockets! Import permits for luxury cars, insurance cover for wives, mistresses and sons and of course plain rip-off.

A sharp middle-aged lady mounting the steps of the Dehiwala-Galkissa Municipal Council alerted me. “Why madam do you look unhappy?” I foolishly asked only to be told-off in pristine Sinhala: “Aiyo, 225-ta kanda dena oone ne” (We have to fed the 225, don’t we). Only then did the penny drop. Bribes to left of us, bribes to right of us! The 225 themselves, their catchers and hangers-on (petrol allowances, salaries for aides and drivers), liquor shop permits and Gamage-type rackets that the SJP pretends it knows nothing about). In total the 225 may be cashing in a few million rupees per MP per annum. How many MPs in the current parliament are clean of such nefarious behaviour? I think less than a dozen.

Now that I am about it, a little more politics. I was, I think, the first person who more than a year ago said very firmly that the presidential election would come down to a race between RW and Anura; and it has. Sajith is wailing in the wilderness and the SLFP and SLPP are weighing the prospects of whether to line-up in the RW or Anura camps. Neither SLFP nor SLPP dare put forward a candidate of their own for fear of being wiped out and polling a miniscule number of votes. It seems increasingly likely that both will plonk into the RW camp.

Buffalo Lal Kantha’s pronouncements have made this more likely. He has in addition claimed that only the JVP and the Udaya Gammanpila party took a stand against the Tamils, opposed any form devolution and supported the military in the war against the Tigers. The import of his words is this. The JVP-NPP is going to be identified at the polls as a Sinhala party and this will have consequences. Will it draw the already radicalised Sinhala-Buddhist youth in larger numbers into the JVP camp or will it damage the JVP’s image? Time will show.

The upper and business classes and the city middle classes are cheering for Ranil. They are hooked on the idea he will be able to deliver economic growth. The Economic Transformation Bill and the Public Financial Management Bill tabled in Parliament on 22 May are intended to reassure the IMF that the road to reform that the Fund has demanded will be diligently implemented. The Fund will then unlock billions of dollars now blocked and also expedite deals with Sovereign Wealth Funds deemed necessary it is claimed to reassure the IMF and international capital. The Governor of the Central Bank is singing the same tune and has joined Ranil’s choral group. It is likely that the duo will float the rupee open-up the economy and privatise galore in the coming period. This will have political consequences.

Let me make a summary of the principal tasks facing the nation.

1. It is conventionally opined that debt restructuring, unlocking billions of dollars in IMF Funds and reaching agreement with Sovereign Bond Holders (profit seeking finance companies) is sine qua non.

2. Increasing earnings from foreign trade, meaning increasing earnings from export (including remittances and tourism) and limiting imports (except production machinery and raw materials for production), is considered vitally important.

3. Frugality in consumption (to the extent feasible with poverty ravaged masses) is desirable.

4. These three steps will it is hoped attract foreign investment into productive sectors.

None of this is new, it is all the subject of interminably long and boring newspaper columns. (When will our columnists learn that brevity is the soul of wit?)

RW is singing along to this tune and his confidence in saying NO to parliamentary elections before or simultaneously with the presidential poll shows that he believes he is playing from a strong hand. He is indulging in populist measures like issuing free-hold land title-deeds to landless Tamils in the Kilinochchi area, making attractive promises about enhancing facilities at the Jaffna Hospital, and insisting that plantation companies honour his pledge to workers of a minimum wage of Rs 1,700 per day. RW is gaming that in a presidential election well over one and a half million Ceylon Tamils, Upcountry Tamils, Muslims and Catholics will vote for him and tip the scales in his favour. (See note below). In the parliamentary elections that will inevitably follow the winner of the presidency will carry the day.

A racist alliance called the Sarvajana Balaya has, in the meantime, raised its head, led by Weerawansa and Gammanpila. It has attracted bankrupt ex-leftists of the Communist Party and ageing Vasudeva. This too will play right into RW’S hand.

Act independently

An ever-increasing number of organisations have taken matters into their own hands and launched initiatives because the government is flat-footed. Let me give you a few examples. Fed up with the inability of successive governments to do anything to combat communal violence, or to be more accurate because of the aggravation of communalism by governments beginning with the denial of citizenship to Tamil plantation workers by D. S. Senanayake, the father of the nation (sic!), through SWRD’s communal politics and JR’s loathing of Tamils, to Chandrika playing politics, a bunch of Buddhist monks took the initiative into their own hands.

The monks went on an expedition to Europe and the US, sought out Tamil links such as the Global Tamil Forum and others and initiated a dialogue. The initiative is now in motion and grass-roots activities are in full swing. Important figures like Karu Jayasuriya (former Speaker), Austin Fernando, Sarvodaya, Jehan Perera’s National Peace Council and Pakiasothy Saravanamuttu’s CPA are involved. Branches have been established in many localities and an active movement is in swing. If communal violence is to be halted and if the state and government are, quite literally, worse than useless, a grass roots people’s movement is needed. It has ben launched ; its name is National Movement for Social Justice.

A second example is the need to foster English language competence in all children as a link language between communities and more important because English is the linguafranca of the world today. (Sounds a bit contradictory, doesn’t it? Wonder what the French feel about the juxtaposition?). Seriously though, English is not just the language of modern technology and business. No, it is in all its pronunciations and accents it has become the 21st Century’s world language essential for everyone. State and government have simply and literally messed up English in Sri Lanka’s schools. So well-intentioned voluntary organisations, often women’s groups, have stepped into the breach.

Two more quick examples and I will stop. Microfinance is now the domain of groups, often women’s societies that have filled the gap since the banking sector has failed to support small and medium enterprises. And finally, cooperatives are providing marketing and investment openings for fishermen. I personally know of one such successful assembly of such entities in Jaffna.

The subject of this part of the essay however is in what ways can the people themselves, organised in various voluntary bodies, do to overcome or replace a sluggish state. To what extent can, for example a popular Peoples’ Planning Council, replace the hiatus created by the absence of a State Planning Agency in Sri Lanka. I think a popular public initiative of this nature can achieve quite a bit.

NOTE: The absolute core Sinhala vote in the country is the infamous “69 lakhs”; maybe 70 now by natural increase. I reckon that the minorities – Ceylon Tamils, Upcountry Tamils, Muslims and Catholics – are about one third of the core Sinhala vote. That is (1/3) x70 about 23 lakhs. This is why I reckon that RW is making a play for a clear majority of this 23-lakhs in the presidential poll.

Features

Police, Politics & The Rule of Law:The Great Betrayals

By Dr. Kingsley Wickremasuriya

Preface

Sri Lanka Police Service is the premier law enforcement agency on the Island and one of its oldest government establishments counting over one and half centuries of existence. During this long history, 36 Inspectors-General of Police – 11 of them from the Colonial Administration, and the rest thereafter – were in charge.

Their periods of office were characterized by riots, coups, insurrections, terrorism, political violence, trade union action, mass protests, and worst of all, the politicization of the institution. The vicissitudes the police had to face were many.

The thrust of this essay is to show how once a force that worked according to the rule of law during the colonial administration turned partial and eventually became an apparatus serving political interests rather than those of the common man. Party politics crept into the picture with the progressive introduction of constitutional reforms. To substantiate his thesis, the writer will draw selectively from material available on various websites and other archival material including Police Commission Reports.

The Portuguese – Dutch Period

The Maritime Provinces of Ceylon were under the Portuguese after their invasion in the 15th Century. The Dutch, who arrived in Sri Lanka in 1602, were able to bring the Maritime Provinces and the Jaffna Peninsula under their rule by 1658. Although they controlled certain areas of the maritime provinces, they did not carry out any serious changes to the existing system of civil administration of the country. The concept of policing in Sri Lanka however, started with the Dutch who saddled the military with the responsibility of policing the City of Colombo.

In 1659, the Colombo Municipal Council (under the Dutch) adopted a resolution to appoint paid guards to protect the city by night. Accordingly, a few soldiers were appointed to patrol the city at night.

They initially opened three police stations, one at the northern entrance to the Fort, a second at the causeway connecting the Fort and Pettah, and a third at Kayman’s Gate in the Pettah. In addition to these, ‘Maduwa’ or the office of Dissawa of Colombo who was a Dutch official at Hulftsdorp, also served as a police station for these suburbs. Thus, it was the Dutch who established the earliest police stations and thus became the forerunners of the police in the country.

The British Period

The Dutch surrendered to the British on February 16, 1796. After the occupation of Colombo by the British, law and order were, for some time, maintained by the military. In 1797 the office of fiscal, which had been abolished was re-created. Governor Fredrick North, having found that the fiscal was over-burdened with the additional duty of supervising the police, obtained the concurrence of the Chief Justice and entrusted the Magistrates and Police Judges with the task of supervising the police.

In 1805 police functions came to be clearly defined. Apart from matters connected with the safety, comfort, and convenience of the people, these also came to be connected with preventing and detecting crime and maintaining law and order. The rank of police constable (PC) was created and it came to be associated with all types of police work. By Act No. 14 of 1806, Colombo was divided into 15 divisions, and PCs were appointed to supervise the divisions.

First Superintendent of Police

Mr. Thomas Oswin, Secretary to the Chief Justice, was appointed the first Superintendent of Police of Colombo. Mr. Lokubanda Dunuwila, who was the Dissawa of Uva, was appointed as the Superintendent of Police for Kandy. He goes into history as the very first Lankan to be a Superintendent of Police.

In 1847 the ranks of Assistant Superintendent of Police and Sub Inspector of Police were created. Inspector De La Harpe was promoted as the first Assistant Superintendent of Police.

The National Police

Robert Campbell, KCMG, was the first Inspector General of Police of British Ceylon. The Governor, who was looking for a dynamic person to reorganize the police on the island, turned to India to obtain the services of a capable officer. The Governor of Bombay recommended Mr. G. W. R. Campbell, who was in charge of the “Ratnagiri Rangers” of the Bombay Police, to shoulder this onerous responsibility.

After serving as chief of police in the Indian province of Ratnagiri, Campbell was appointed by Governor Frederick North on September 3, 1866, as Chief Superintendent of Police in Ceylon, in charge of the police force and assumed duties on September 3, 1866. This date is thus reckoned as the beginning of the Sri Lanka Police Service.

Campbell is credited with shaping the force into an efficient organization and giving it a distinct identity. He brought the whole island under his purview and the police became a national rather than a local force. In 1867, by an amendment to the Police Ordinance No. 16 of 1865, the designation of the Head of the Police Force was changed from Chief Superintendent to Inspector-General of Police. In 1887 he was awarded the CMG. On his retirement, he received a knighthood for his service.

Apart from Campbell, 35 others were in charge of the Police Force in Sri Lanka. They performed to different degrees of standards contributing to the development or the decline of the police service in Sri Lanka. Cyril Longdon, the sixth Inspector-General was instrumental in establishing a Police Training School for recruits and a Criminal Investigation Department.

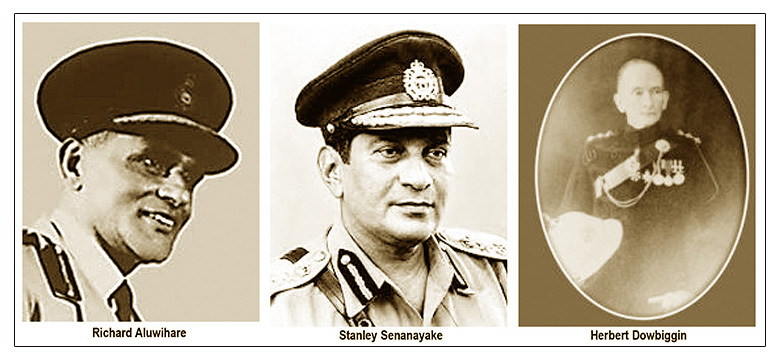

Ivor Edward David was the seventh British colonial Inspector-General of Police in Ceylon (1910-1913). During his tenure, David was noted for establishing the POLICE SPORTS GROUNDS in Bambalapitiya in 1912. Dowbiggin succeeded him as Inspector-General of Police.

Sir Herbert Layard Dowbiggin, CMG, was the eighth British colonial Inspector General of Police of Ceylon from 1913 to 1937, the longest tenure of office of an Inspector General of Police. He was called the ‘Father of the Colonial Police’. Dowbiggin joined the Ceylon Police Force in 1901 and became Inspector General in 1913.

During his tenure, the strength of the force was enhanced considerably with the posts of two deputy inspectors general were created. He oversaw an expansion of the force: the number of police stations increased so that by 1916 there were 138 all over the island. He also modernized the force, introducing new techniques of investigation such as fingerprinting and photography; improving the telecommunications network for the police as well as increasing the mobility of the force. The analysis of crime reports became more systematic. He purchased the land on Havelock Road, Colombo, on which the Field Force Headquarters and the ‘Police Park’ playing fields are located. He was knighted in 1931.

First Sri Lankan Inspector General

Beginning with Sir Richard Aluwihare, KCMG, CBE, JP, CCS, 25 others served as IGPs thereafter. Sir Richard was a Sri Lankan civil servant and the first Ceylonese IGP who later served as Ceylon’s High Commissioner to India. The Police Department, which was under the Home Ministry, was brought under the purview of the Defense Ministry during his tenure.

Sir Richard faced the unenviable responsibility of transforming the police from its colonial outlook to a national police with the gaining of independence in 1948. To this end, he introduced a large number of innovative measures embracing the welfare of the men, investigation, prevention, and detection of crime, the women police, crime prevention societies, rural volunteers, police kennels, public relations, new methods of training and improvement of conditions of service.

He transformed what was a Police Force into a Police Service. Its role was narrowly defined and restricted to the maintenance of law and order and the prevention and detection of crime. In 1948 he established the Police Training School in Kalutara.

He retired from the civil service as IGP and was succeeded by his son-in-law Osmund de Silva. Santiago Wilson Osmund de Silva, OBE was the 13th and the first Ceylonese career police officer to become Inspector-General of Police (1955–1959). In 1955 he succeeded his father-in-law, Sir Richard Aluwihare to be appointed IGP. He became the first IGP appointed from within the police force and the first Buddhist. He introduced community policing to the country, a vision not shared by his successors.

The Great Betrayals

It was during his tenure that Prime Minster Bandaranaike is reported to have exhorted IGP Osmund de Silva that the police should have that ’extra bit of loyalty’ to the government. The response to this by the IGP was an exhortation to his officers that what they should uphold is the Rule of Law. He said this knowing that he would be falling out of favour with the premier and that it would affect his tenure. This assertion by the IGP came when there was no Bill of Rights in the Parliament or no Republican Constitution with Fundamental Rights to fall back on.

Thereafter, when the Prime Minister, S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike requested that the police intervene against trade union action occurring at Colombo Port. De Silva declined to do the PM’s bidding on the basis that he believed the request was unlawful. On April 24, 1959, de Silva was compulsorily retired from the police force with M. Walter F. Abeykoon, a senior public servant, appointed in his place.

This was the first betrayal by the head of government ignoring an entrenched police norm held sacrosanct through almost a century by the colonial administrators. It eventually led to a near mutiny by the police top brass and later even to more serious consequences of a coup the government managed to avoid by a stroke of luck.

Morawakkorakoralege Walter Fonseka Abeykoon served IGP between 1959 and 1963. He was appointed to this position May 1, 1959 by his personal friend and bridge partner, Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. The appointment was highly controversial as the PM appointed Abeykoon from outside the service by-passing several senior career police officers, on the basis that Abeykoon was a Sinhala Buddhist.

Senior police officers protested and DIG C. C. Dissanayake tendered his resignation, which was later withdrawn. The senior police officers, who were predominantly Christian, fearing a calamity, met to consider their options. They considered whether the entire police executive resigned on masse, although they decided against this as they thought it had the potential to cause the entire police service to collapse. Alternatively, they surveyed the Executive Corps for the senior- most officer among them who was a Buddhist and could find only young SP Stanley Senanayake.

They resolved to make representations to the Prime Minister that they were prepared to work under Stanley who was junior to all of them rather than having to work under an outsider with no experience who knew nothing of Police or the Police Ordinance. Bandaranaike however ignored their representations and appointed Abeykoon. In 1962, when a coup d’état was attempted by senior officers of the military and police, Abeykoon was caught off guard. Early warning from one of the conspirators, however, allowed the government to respond in time. Ironically, Stanley Senanayake was the whistle blower and the information was conveyed to IGP Abeykoon by P. de S. Kularatne, Senanayake’s father-in-law.

Thereafter, Benjamin Lakdasa ‘Lucky’ Victor de Silva Kodituwakku was appointed as the Inspector General of Police on September 1, 1998 by President Chandrika Kumaratunga following the retirement of Wickremasinghe Rajaguru on August 31, 1998 . This was a controversial appointment, his being selected over five other DIGs with greater seniority. Allegedly this appointment was influenced by the ruling party.

Kodituwakku, while in charge of the Kelaniya Police Division as SP, received transfer orders to go into charge of the Jaffna Police Division. He tried his best to get the transfer canceled but the department stood firm on its policy decision that every police officer needed to serve Jaffna for one year during the LTTE threat.

He opted to leave the service in 1984 resigning his post when he failed to circumvent the transfer. Following his resignation, he worked as a security consultant in a private company and was out of the Police Service for over one-and-a-half decades.

However, following the election of the People’s Alliance government at the 1994 parliamentary elections the new government enabled public servants who had faced alleged “political victimization” to appeal for reinstatement and back wages. Making use of this opportunity Kodituwakku re-joined the service and on October 1, 1997, was promoted to DIGl and Senior DIG rank on August 2, 1998 (a double promotion, from the rank of SSP ignoring the fact that he refused to go on transfer to Jaffna and resigned defying a mandatory policy decision taken by the Department that applied to every servicing police officer.

Kodituwakku was the Inspector-General at the time the Waymaba Provincial Council Elections took place. He was blamed for the violence and the election malpractices that took place during the elections. The 17th Amendment to the Constitution was the result of a political initiative launched by Members of Parliament in the Opposition led by the United National Party in 2001 as a response to the Wayamba Election Episode.

This was the second betrayal by a Head of State- President Chandrika Kumaratunga- when she decided to appoint Lucky Kodituwakku the 26th IGP ignoring so many other seniors over him just because of the special position he enjoyed as the Personal Security officer (PSO) of a VVIP that gave him an advantage over his seniors to canvass for the post. Wayamba- election- bungling and the 17th Amendment to the Constitution was the result.

These precedents led to yet other betrayals last of which was when Deshabndu Tennakoon came to be appointed by the current President Ranil Wickremasinghe as the 36th IGP even though the Supreme Court held that Deshabandu was guilty of human rights violations.

Tennakoon Mudiyanselage Wanshalankara Deshabandu Tennakoon (born 3 July 1971), known as Deshabandu Tennakoon is the current Inspector General of the Sri Lankan Police.

On 14 December 2023, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka ruled that Tennakoon and two of his subordinates were guilty of torturing Weheragedara Ranjith Sumangala of Kindelpitiya for alleged theft and thereby violating his fundamental rights when the men were in uniform attached to the Nugegoda Police Division in 2010.

The Fundamental Rights Application (SC/FR 107/2011) was filled by Sumangala in the Supreme Court in March 2011, against the then Superintendent of Police, M.W.D. Tennakoone, Inspector of Police Bhathiya Jayasinghe, then OIC (Emergency Unit) Mirihana, Police Officer Bandara, former Sergeant Major Ajith Wanasundera of Padukka, and several others in the police department. The three bench panel consisting of Justices S. Thurairaja, Kumudini Wickremasinghe, and Priyantha Fernando, directed the National Police Commission and other relevant authorities to take disciplinary action against Tennakoon and two of his subordinates.

On 29 November 2023, President Ranil Wickremesinghe however, appointed Tennakoon as acting Inspector General of Police. He was appointed as the permanent Inspector General of Police on 26 February 2024.

The same day that he was appointed to the post of Inspector General of Police, Leader of the Opposition Sajith Premadasa claimed that the Constitutional Council, which oversees high-level appointments, saw only four votes cast in favor of Tennakoon. In comparison, two votes were cast against and there were two abstentions. Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, counting the abstentions as votes against exercised his casting vote to break the tie in Tennekoon’s favour. This matter is currently being canvassed in the Supreme Court.

(To be continued)

kingsley.wickremasuriya@gmail.com