Features

Ridi Vihare: A temple and a book

Ridi Vihare: The Flowering of Kandyan Art

Dr. SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda

Stamford Lake Publications, 2006, pp. 210, Rs 3,750

Reviewed

by Uditha Devapriya

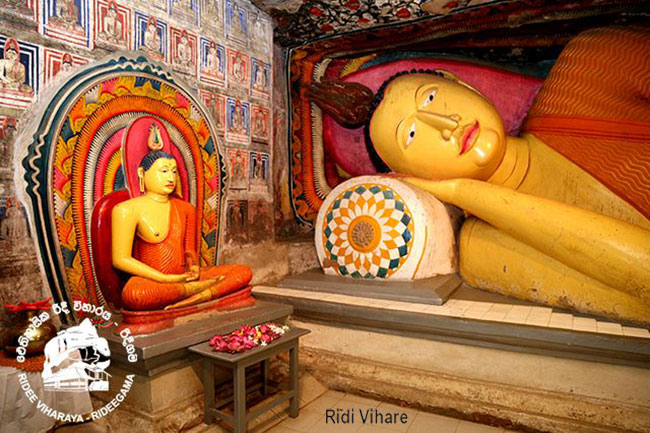

This is a fascinating study of one of the more fascinating Buddhist temples of Sri Lanka, authored by one of our foremost historians. The Ridi Vihare, or the ‘Silver Temple’, traces its history to the second century BC. It occupied a prominent place until the 14th century AD, when it disappeared from view. Three hundred years later, during the time of the Nayakkar kings of Kandy, it regained that position. What Dr. SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda attempts in his book is to explore its history and its art, viewing them not in isolation but in unison. The result is a superb work of scholarship, at once edifying and accessible.

Though written 15 years ago, before even the civil war ended, the scope and breadth of ‘Ridi Vihare: The Flowering of Kandyan Art’ resonates well even today. Partly, that is because Sri Lanka’s Buddhist temples have never become the object of study that religious institutions elsewhere have. This is certainly an unfortunate omission, a glaring one.

Though written 15 years ago, before even the civil war ended, the scope and breadth of ‘Ridi Vihare: The Flowering of Kandyan Art’ resonates well even today. Partly, that is because Sri Lanka’s Buddhist temples have never become the object of study that religious institutions elsewhere have. This is certainly an unfortunate omission, a glaring one.

While the Sangha has been studied as an institution, most discernibly by Leslie Gunawardana, very few have tried to understand the social history of Buddhist temples. It is to the likes of Senake Bandaranayake that we owe our understanding of this aspect of our culture. The finest historian of art to come out of the country, Dr. Bandaranayake authored the finest work of scholarship on Buddhist art. Yet while ‘The Rock and Wall Paintings of Sri Lanka’ remains essential reading, it is a testament to where we are now and how we regard our past that since its publication, no comparable effort has come out.

Sinhala historians frequently do write monographs on these institutions, and many of them are available for cheap and even free, often at the very places their monographs are about. Yet while such efforts are laudable, they are hardly enough. To highlight the uniqueness of these places, it is necessary to dig deeper, to go beyond essays, to put the Buddhist temple of Sri Lanka in its proper historical context. Such an undertaking requires time and money, a sense of purpose, an overwhelming desire to probe.

It is that purpose and desire which colours Dr. Tammita-Delgoda’s outstanding work. It stands out not so much as a scholarly foray as a labour of love, an exploration into our past, who we are, and what we make of ourselves. Interspersed with photographs, diagrams, and illustrations, all painstakingly taken and meticulously captioned, the book doesn’t just focus on the temple, it uses it as the base from which to explore everything around it. As Dr. Siran Deraniyagala informs us in the introduction, Ridi Vihare offers no less than “a microcosm of Sri Lanka’s turbulent past.” This is a point the author engages with constantly.

It is that purpose and desire which colours Dr. Tammita-Delgoda’s outstanding work. It stands out not so much as a scholarly foray as a labour of love, an exploration into our past, who we are, and what we make of ourselves. Interspersed with photographs, diagrams, and illustrations, all painstakingly taken and meticulously captioned, the book doesn’t just focus on the temple, it uses it as the base from which to explore everything around it. As Dr. Siran Deraniyagala informs us in the introduction, Ridi Vihare offers no less than “a microcosm of Sri Lanka’s turbulent past.” This is a point the author engages with constantly.

How the book came about is as interesting as what it contains. Due to the high position it occupied in late mediaeval Sri Lanka, Ridi Vihare forged ties with Malwathu Maha Viharaya, one of the two Buddhist monastic chapters within the Siam Nikaya. Over the last 250 years, three of the Chief Incumbents of Ridi Vihare have wound up as Chief Prelates of Malwatta.

It was one of these Chief Prelates, Thibbotuwawe Sri Siddhartha Sumangala Thera, who took over the task of teaching “the religion, the philosophy and the customs of the Sinhalese” to the author. After his stint ended, Sumangala Thera requested his erstwhile student to write about the temple he was serving and officiating at the time. It was as a result of his request, and the author’s only too eager response, that this book came about.

Writing the book was not easy. Having begun in 1998, Dr. Tammita-Delgoda had to stop mid-way. The main problem was funding; not so much for travel or research as for photography. Desperately in need of money, and with no one to get it from, the entire project had to be stalled for several years. It was picked up again only through the intervention of a much loved icon: Sri Lanka’s most celebrated photographer, Nihal Fernando, who agreed to undertake its photography through his outfit, Studio Times, at no cost.

Thanks to Fernando’s support and the assistance of friends, patrons, and well-wishers, Dr. Tammita-Delgoda found himself digging deep into the history of the land. Having planned it as the story of a temple, his project soon became so much more.

The history of Ridi Vihare begins with “the greatest king of Anuradhapura”, Dutugemunu, in the second century BC. The Mahavamsa records Dutugemunu as the first of the Sinhalese kings who unified the country. Having achieved this task, he embarked on the construction of stupas, the last of which, the Mahathupa, became a huge undertaking. It was in reply to his prayer, that money be found for the Mahathupa, that silver was found at a cave called Ambattakola in Kurunegala. As a token of gratitude, Dutugemunu had a temple built by a jackfruit tree near that cave. It is here that the Varaka Velandhu Vihare, the oldest and perhaps most important establishment at Ridi Vihare, stands today.

As with all such institutions, the temple amply reflected its times. By the time of the Polonnaruwa kingdom, South Indian influences began making their way to the Ridi Vihare. We are told that a Hindu devale was constructed within the courtyard somewhere after the 12th Century. Though popular writers portray this as a period of decay and destruction, it was also a period of cultural fusion. Ridi Vihare did not escape such influences, in spite of the impoverished conditions of these years. It remained a centrepiece of the kingdom well into the 14th Century, though once the capital of the Sinhalese polity shifted from Wayamba to Kotte to Kanda Uda Rata it fell into much decay, decline, and disrepair.

The next chapter of Ridi Vihare unfolds at the time of the Kandyan kings, specifically the Nayakkars and particularly the reign of the second of them, Kirti Sri Rajasinghe. An ardent, passionate patron of Buddhism, Rajasinghe oversaw a period of renaissance marked by the resumption of the ordination of monks, a practice that had fallen into neglect for centuries. We are told of the political conditions prevalent at the time, the ambiguities that dotted the Nayakkars’ rule over an eminently Buddhist realm, and the rebellions against them aided by none less than the leading revivalist of his time, Weliwita Sri Saranankara Thera.

In the course of his reign Kirti Sri Rajasinghe brought Buddhist monasteries under the sway of Malwatta and Asgiriya. This had a profound impact on not just Ridi Vihare, but also the Sangha. It had much to do with the personality of the king himself.

As an outsider looking in, Rajasinghe had to show that he was the true heir to his Sinhalese predecessors. Though Leslie Gunawardana and Gananath Obeyesekere have suggested that opposition to Nayakkar rule was not as prevalent as popular writers make it out to be, there was opposition, and it was considerable. His motives were constantly under scrutiny by the radala aristocracy and clergy, and he needed to prove himself worthy in their eyes. To let go and belittle their concerns was to invite disenchantment and dissent.

It was against this backdrop that Kirti Sri Rajasinghe pursued a policy of detente and then confrontation with Dutch governors, while sponsoring efforts at purifying the Sangha and expelling foreign elements within his kingdom who had been indulged by his predecessors. Spilling over to the religious institutions of his realm, these efforts transformed Ridi Vihare into a leading centre of learning and study, in particular under Thibbotuwawe Sri Siddhartha Buddharakkitha Thera, the closest disciple of Weliwita Sri Saranankara Thera.

Partly due to his upcountry ancestry, Dr. Tammita-Delgoda is at his best in these chapters, when he is charting the social and artistic history of the last Sinhalese kingdom. Having read and researched his sources well, he goes beyond them, conjecturing about the reputation Ridi Vihare would have enjoyed under Buddharakkitha. He takes pains to emphasise that though Kandy was at war with the Dutch, this did not preclude contact between officials and Buddhist monks, a point that shows well in the Delft tiles at the Maha Vihara of Ridi Vihare. Long thought to be a gift from the Dutch Governor to the Vihare’s Chief Incumbent, these objects shed light on the nature of relations between Kandy and Holland.

From historicising Ridi Vihare, Dr. Tammita-Delgoda goes on to deconstruct its topography, periodising its construction from the pre-Christian era to the 20th Century. He then delves into the paintings and sculptures at the temple. With more than a connoisseur’s eye for the elegant and the sublime, he expresses much distaste for contemporary efforts at repairing the site, particularly the “hideous” restored vahalkada at its entrance. In exploring the inner courtyards and sanctums, he also attempts to reconstruct life as it would have been back in the day, especially through the use of archive images and illustrations.

There is clearly an art historian lurking beneath the historian, and in the chapters on the art and sculpture of Ridi Vihare Dr. Tammita-Delgoda lets him out. Not surprisingly, these make up some of the best forays into Kandyan art and architecture I have read.

Colonial officials and scholars often painted Kandy as a period of cultural decay, a pale reflection of the classical art that once prevailed in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. Such generalisations were questioned, rightly, by the likes of Dr. Senake Bandaranayake and Siri Gunasinghe. Dr. Tammita-Delgoda continues their line of critique, unearthing Kandyan art for what it is and not for what it is often imagined to be. Its aim, he observes, was to appeal to devotees, not conform to European rules of perspective and representation.

Because of these insights, the sections on the paintings and sculptures of Ridi Vihare are the most edifying in the book. Even more edifying is the final chapter, a personal meditation on the nature of Sinhalese art. Dr. Tammita-Delgoda provocatively calls it the “art of the poor people”, as it indeed was. Reflecting on Ananda Coomaraswamy’s Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, he contends that the world around these temples shaped their architecture, differentiating them from the much larger monuments of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa.

Because of these insights, the sections on the paintings and sculptures of Ridi Vihare are the most edifying in the book. Even more edifying is the final chapter, a personal meditation on the nature of Sinhalese art. Dr. Tammita-Delgoda provocatively calls it the “art of the poor people”, as it indeed was. Reflecting on Ananda Coomaraswamy’s Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, he contends that the world around these temples shaped their architecture, differentiating them from the much larger monuments of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa.

Scholars may consider that a defect in Kandyan architecture, but it was a form shaped by the society around it and the privations imposed by colonialism. Hemmed in from all sides, Kandyan temples could not aspire to the gigantism of earlier periods. That they managed to attract devotion and patronage despite this is, in that sense, truly remarkable.

A book like this contains few flaws, indeed almost none at all. Its only limitation is its lack of focus on the material conditions of Kandyan society, the contributions of the people to the construction of these edifices, and the point that such institutions were as much the work of kings and monks as of the citizenry. Dr. Tammita-Delgoda does identify the painters of Ridi Vihare and their backgrounds, but all too often he implies that kings, aristocrats, and monks were all that mattered in 18th Century Kandy. What were the conjunctions of class and caste that produced these magnificent edifices? We clearly need to know more.

Nevertheless, as a labour of love and a token of gratitude to the monks who tutored the author, ‘Ridi Vihare: The Flowering of Kandyan Art’ remains a first-rate work, the first of many that would follow. What it shows us is a pathway to the past, a way of life which modernity has eroded. Seeing it, one can only quote Ananda Coomaraswamy.

“In the words of Blake,

‘When nations grow old,

The Arts grow cold,

And commerce settles on every tree’.

In such a grim fashion has commerce settled in the East.”

If we don’t make sense of our past, we are doomed to forget it. The result can only be a hideous reconfiguration and reconstruction of our identity, a distortion that bears little to no resemblance to who we once were. It is this point that Dr. SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda brings up, a point we would do well to acknowledge and to heed.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

The heart-friendly health minister

by Dr Gotabhya Ranasinghe

Senior Consultant Cardiologist

National Hospital Sri Lanka

When we sought a meeting with Hon Dr. Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Health, he graciously cleared his busy schedule to accommodate us. Renowned for his attentive listening and deep understanding, Minister Pathirana is dedicated to advancing the health sector. His openness and transparency exemplify the qualities of an exemplary politician and minister.

Dr. Palitha Mahipala, the current Health Secretary, demonstrates both commendable enthusiasm and unwavering support. This combination of attributes makes him a highly compatible colleague for the esteemed Minister of Health.

Our discussion centered on a project that has been in the works for the past 30 years, one that no other minister had managed to advance.

Minister Pathirana, however, recognized the project’s significance and its potential to revolutionize care for heart patients.

The project involves the construction of a state-of-the-art facility at the premises of the National Hospital Colombo. The project’s location within the premises of the National Hospital underscores its importance and relevance to the healthcare infrastructure of the nation.

This facility will include a cardiology building and a tertiary care center, equipped with the latest technology to handle and treat all types of heart-related conditions and surgeries.

Securing funding was a major milestone for this initiative. Minister Pathirana successfully obtained approval for a $40 billion loan from the Asian Development Bank. With the funding in place, the foundation stone is scheduled to be laid in September this year, and construction will begin in January 2025.

This project guarantees a consistent and uninterrupted supply of stents and related medications for heart patients. As a result, patients will have timely access to essential medical supplies during their treatment and recovery. By securing these critical resources, the project aims to enhance patient outcomes, minimize treatment delays, and maintain the highest standards of cardiac care.

Upon its fruition, this monumental building will serve as a beacon of hope and healing, symbolizing the unwavering dedication to improving patient outcomes and fostering a healthier society.We anticipate a future marked by significant progress and positive outcomes in Sri Lanka’s cardiovascular treatment landscape within the foreseeable timeframe.

Features

A LOVING TRIBUTE TO JESUIT FR. ALOYSIUS PIERIS ON HIS 90th BIRTHDAY

by Fr. Emmanuel Fernando, OMI

Jesuit Fr. Aloysius Pieris (affectionately called Fr. Aloy) celebrated his 90th birthday on April 9, 2024 and I, as the editor of our Oblate Journal, THE MISSIONARY OBLATE had gone to press by that time. Immediately I decided to publish an article, appreciating the untiring selfless services he continues to offer for inter-Faith dialogue, the renewal of the Catholic Church, his concern for the poor and the suffering Sri Lankan masses and to me, the present writer.

It was in 1988, when I was appointed Director of the Oblate Scholastics at Ampitiya by the then Oblate Provincial Fr. Anselm Silva, that I came to know Fr. Aloy more closely. Knowing well his expertise in matters spiritual, theological, Indological and pastoral, and with the collaborative spirit of my companion-formators, our Oblate Scholastics were sent to Tulana, the Research and Encounter Centre, Kelaniya, of which he is the Founder-Director, for ‘exposure-programmes’ on matters spiritual, biblical, theological and pastoral. Some of these dimensions according to my view and that of my companion-formators, were not available at the National Seminary, Ampitiya.

Ever since that time, our Oblate formators/ accompaniers at the Oblate Scholasticate, Ampitiya , have continued to send our Oblate Scholastics to Tulana Centre for deepening their insights and convictions regarding matters needed to serve the people in today’s context. Fr. Aloy also had tried very enthusiastically with the Oblate team headed by Frs. Oswald Firth and Clement Waidyasekara to begin a Theologate, directed by the Religious Congregations in Sri Lanka, for the contextual formation/ accompaniment of their members. It should very well be a desired goal of the Leaders / Provincials of the Religious Congregations.

Besides being a formator/accompanier at the Oblate Scholasticate, I was entrusted also with the task of editing and publishing our Oblate journal, ‘The Missionary Oblate’. To maintain the quality of the journal I continue to depend on Fr. Aloy for his thought-provoking and stimulating articles on Biblical Spirituality, Biblical Theology and Ecclesiology. I am very grateful to him for his generous assistance. Of late, his writings on renewal of the Church, initiated by Pope St. John XX111 and continued by Pope Francis through the Synodal path, published in our Oblate journal, enable our readers to focus their attention also on the needed renewal in the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka. Fr. Aloy appreciated very much the Synodal path adopted by the Jesuit Pope Francis for the renewal of the Church, rooted very much on prayerful discernment. In my Religious and presbyteral life, Fr.Aloy continues to be my spiritual animator / guide and ongoing formator / acccompanier.

Fr. Aloysius Pieris, BA Hons (Lond), LPh (SHC, India), STL (PFT, Naples), PhD (SLU/VC), ThD (Tilburg), D.Ltt (KU), has been one of the eminent Asian theologians well recognized internationally and one who has lectured and held visiting chairs in many universities both in the West and in the East. Many members of Religious Congregations from Asian countries have benefited from his lectures and guidance in the East Asian Pastoral Institute (EAPI) in Manila, Philippines. He had been a Theologian consulted by the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences for many years. During his professorship at the Gregorian University in Rome, he was called to be a member of a special group of advisers on other religions consulted by Pope Paul VI.

Fr. Aloy is the author of more than 30 books and well over 500 Research Papers. Some of his books and articles have been translated and published in several countries. Among those books, one can find the following: 1) The Genesis of an Asian Theology of Liberation (An Autobiographical Excursus on the Art of Theologising in Asia, 2) An Asian Theology of Liberation, 3) Providential Timeliness of Vatican 11 (a long-overdue halt to a scandalous millennium, 4) Give Vatican 11 a chance, 5) Leadership in the Church, 6) Relishing our faith in working for justice (Themes for study and discussion), 7) A Message meant mainly, not exclusively for Jesuits (Background information necessary for helping Francis renew the Church), 8) Lent in Lanka (Reflections and Resolutions, 9) Love meets wisdom (A Christian Experience of Buddhism, 10) Fire and Water 11) God’s Reign for God’s poor, 12) Our Unhiddden Agenda (How we Jesuits work, pray and form our men). He is also the Editor of two journals, Vagdevi, Journal of Religious Reflection and Dialogue, New Series.

Fr. Aloy has a BA in Pali and Sanskrit from the University of London and a Ph.D in Buddhist Philosophy from the University of Sri Lankan, Vidyodaya Campus. On Nov. 23, 2019, he was awarded the prestigious honorary Doctorate of Literature (D.Litt) by the Chancellor of the University of Kelaniya, the Most Venerable Welamitiyawe Dharmakirthi Sri Kusala Dhamma Thera.

Fr. Aloy continues to be a promoter of Gospel values and virtues. Justice as a constitutive dimension of love and social concern for the downtrodden masses are very much noted in his life and work. He had very much appreciated the commitment of the late Fr. Joseph (Joe) Fernando, the National Director of the Social and Economic Centre (SEDEC) for the poor.

In Sri Lanka, a few religious Congregations – the Good Shepherd Sisters, the Christian Brothers, the Marist Brothers and the Oblates – have invited him to animate their members especially during their Provincial Congresses, Chapters and International Conferences. The mainline Christian Churches also have sought his advice and followed his seminars. I, for one, regret very much, that the Sri Lankan authorities of the Catholic Church –today’s Hierarchy—- have not sought Fr.

Aloy’s expertise for the renewal of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka and thus have not benefited from the immense store of wisdom and insight that he can offer to our local Church while the Sri Lankan bishops who governed the Catholic church in the immediate aftermath of the Second Vatican Council (Edmund Fernando OMI, Anthony de Saram, Leo Nanayakkara OSB, Frank Marcus Fernando, Paul Perera,) visited him and consulted him on many matters. Among the Tamil Bishops, Bishop Rayappu Joseph was keeping close contact with him and Bishop J. Deogupillai hosted him and his team visiting him after the horrible Black July massacre of Tamils.

Features

A fairy tale, success or debacle

Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement

By Gomi Senadhira

senadhiragomi@gmail.com

“You might tell fairy tales, but the progress of a country cannot be achieved through such narratives. A country cannot be developed by making false promises. The country moved backward because of the electoral promises made by political parties throughout time. We have witnessed that the ultimate result of this is the country becoming bankrupt. Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet.” – President Ranil Wickremesinghe, 2024 Budget speech

Any Sri Lankan would agree with the above words of President Wickremesinghe on the false promises our politicians and officials make and the fairy tales they narrate which bankrupted this country. So, to understand this, let’s look at one such fairy tale with lots of false promises; Ranil Wickremesinghe’s greatest achievement in the area of international trade and investment promotion during the Yahapalana period, Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (SLSFTA).

It is appropriate and timely to do it now as Finance Minister Wickremesinghe has just presented to parliament a bill on the National Policy on Economic Transformation which includes the establishment of an Office for International Trade and the Sri Lanka Institute of Economics and International Trade.

Was SLSFTA a “Cleverly negotiated Free Trade Agreement” as stated by the (former) Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Malik Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate on the SLSFTA in July 2018, or a colossal blunder covered up with lies, false promises, and fairy tales? After SLSFTA was signed there were a number of fairy tales published on this agreement by the Ministry of Development Strategies and International, Institute of Policy Studies, and others.

However, for this article, I would like to limit my comments to the speech by Minister Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate, and the two most important areas in the agreement which were covered up with lies, fairy tales, and false promises, namely: revenue loss for Sri Lanka and Investment from Singapore. On the other important area, “Waste products dumping” I do not want to comment here as I have written extensively on the issue.

1. The revenue loss

During the Parliamentary Debate in July 2018, Minister Samarawickrama stated “…. let me reiterate that this FTA with Singapore has been very cleverly negotiated by us…. The liberalisation programme under this FTA has been carefully designed to have the least impact on domestic industry and revenue collection. We have included all revenue sensitive items in the negative list of items which will not be subject to removal of tariff. Therefore, 97.8% revenue from Customs duty is protected. Our tariff liberalisation will take place over a period of 12-15 years! In fact, the revenue earned through tariffs on goods imported from Singapore last year was Rs. 35 billion.

The revenue loss for over the next 15 years due to the FTA is only Rs. 733 million– which when annualised, on average, is just Rs. 51 million. That is just 0.14% per year! So anyone who claims the Singapore FTA causes revenue loss to the Government cannot do basic arithmetic! Mr. Speaker, in conclusion, I call on my fellow members of this House – don’t mislead the public with baseless criticism that is not grounded in facts. Don’t look at petty politics and use these issues for your own political survival.”

I was surprised to read the minister’s speech because an article published in January 2018 in “The Straits Times“, based on information released by the Singaporean Negotiators stated, “…. With the FTA, tariff savings for Singapore exports are estimated to hit $10 million annually“.

As the annual tariff savings (that is the revenue loss for Sri Lanka) calculated by the Singaporean Negotiators, Singaporean $ 10 million (Sri Lankan rupees 1,200 million in 2018) was way above the rupees’ 733 million revenue loss for 15 years estimated by the Sri Lankan negotiators, it was clear to any observer that one of the parties to the agreement had not done the basic arithmetic!

Six years later, according to a report published by “The Morning” newspaper, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) on 7th May 2024, Mr Samarawickrama’s chief trade negotiator K.J. Weerasinghehad had admitted “…. that forecasted revenue loss for the Government of Sri Lanka through the Singapore FTA is Rs. 450 million in 2023 and Rs. 1.3 billion in 2024.”

If these numbers are correct, as tariff liberalisation under the SLSFTA has just started, we will pass Rs 2 billion very soon. Then, the question is how Sri Lanka’s trade negotiators made such a colossal blunder. Didn’t they do their basic arithmetic? If they didn’t know how to do basic arithmetic they should have at least done their basic readings. For example, the headline of the article published in The Straits Times in January 2018 was “Singapore, Sri Lanka sign FTA, annual savings of $10m expected”.

Anyway, as Sri Lanka’s chief negotiator reiterated at the COPF meeting that “…. since 99% of the tariffs in Singapore have zero rates of duty, Sri Lanka has agreed on 80% tariff liberalisation over a period of 15 years while expecting Singapore investments to address the imbalance in trade,” let’s turn towards investment.

Investment from Singapore

In July 2018, speaking during the Parliamentary Debate on the FTA this is what Minister Malik Samarawickrama stated on investment from Singapore, “Already, thanks to this FTA, in just the past two-and-a-half months since the agreement came into effect we have received a proposal from Singapore for investment amounting to $ 14.8 billion in an oil refinery for export of petroleum products. In addition, we have proposals for a steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million), sugar refinery ($ 200 million). This adds up to more than $ 16.05 billion in the pipeline on these projects alone.

And all of these projects will create thousands of more jobs for our people. In principle approval has already been granted by the BOI and the investors are awaiting the release of land the environmental approvals to commence the project.

I request the Opposition and those with vested interests to change their narrow-minded thinking and join us to develop our country. We must always look at what is best for the whole community, not just the few who may oppose. We owe it to our people to courageously take decisions that will change their lives for the better.”

According to the media report I quoted earlier, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) Chief Negotiator Weerasinghe has admitted that Sri Lanka was not happy with overall Singapore investments that have come in the past few years in return for the trade liberalisation under the Singapore-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement. He has added that between 2021 and 2023 the total investment from Singapore had been around $162 million!

What happened to those projects worth $16 billion negotiated, thanks to the SLSFTA, in just the two-and-a-half months after the agreement came into effect and approved by the BOI? I do not know about the steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million) and sugar refinery ($ 200 million).

However, story of the multibillion-dollar investment in the Petroleum Refinery unfolded in a manner that would qualify it as the best fairy tale with false promises presented by our politicians and the officials, prior to 2019 elections.

Though many Sri Lankans got to know, through the media which repeatedly highlighted a plethora of issues surrounding the project and the questionable credentials of the Singaporean investor, the construction work on the Mirrijiwela Oil Refinery along with the cement factory began on the24th of March 2019 with a bang and Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his ministers along with the foreign and local dignitaries laid the foundation stones.

That was few months before the 2019 Presidential elections. Inaugurating the construction work Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said the projects will create thousands of job opportunities in the area and surrounding districts.

The oil refinery, which was to be built over 200 acres of land, with the capacity to refine 200,000 barrels of crude oil per day, was to generate US$7 billion of exports and create 1,500 direct and 3,000 indirect jobs. The construction of the refinery was to be completed in 44 months. Four years later, in August 2023 the Cabinet of Ministers approved the proposal presented by President Ranil Wickremesinghe to cancel the agreement with the investors of the refinery as the project has not been implemented! Can they explain to the country how much money was wasted to produce that fairy tale?

It is obvious that the President, ministers, and officials had made huge blunders and had deliberately misled the public and the parliament on the revenue loss and potential investment from SLSFTA with fairy tales and false promises.

As the president himself said, a country cannot be developed by making false promises or with fairy tales and these false promises and fairy tales had bankrupted the country. “Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet”.

(The writer, a specialist and an activist on trade and development issues . )