Midweek Review

Power of the metaphor in Kafka’s ‘The metamorphosis’

By DR. SIRI GALHENAGE

Psychiatrist

The defining quality of literature is the expression of human nature in its diversity and its vicissitudes. Characters, their patterns of behaviour, and the situations they create, originate from our ‘universally shared experience’, etched in our ‘collective unconscious’ through repeated occurrence since antiquity [Carl Jung]. Metaphors are generated by the creative powers of the human mind to enhance literary artistry in portraying such archetypal forms and themes.

The Metaphor

Writing in his Poetics, Aristotle asserted that, “to be a master of metaphor is the greatest thing by far. It is the one thing that cannot be learnt from others, and it is also a sign of genius.” Modern thinking is that the ability to generate metaphors is acquired in varying degree by genetic evolution – a maturational process of the human brain with its interaction with nature – bringing about an alignment between science and the arts.

The word metaphor originates from Greek meta [beyond] + pherein [to carry] – ‘something carried beyond another, or likened to another as if it were that other’ – figuratively, as opposed to literally. Even if the ‘primary subject’ is carried beyond the bounds of reality and transformed into a ‘secondary subject’ of fantasy, it remains anchored to its human origins. The metaphor challenges our resources for thinking while enriching our minds. The simile [derived from Latin – similis – alike], its less sophisticated cousin, on the other hand, points out the likeness of two generally unlike objects, leaving less room for imagination!

Novella

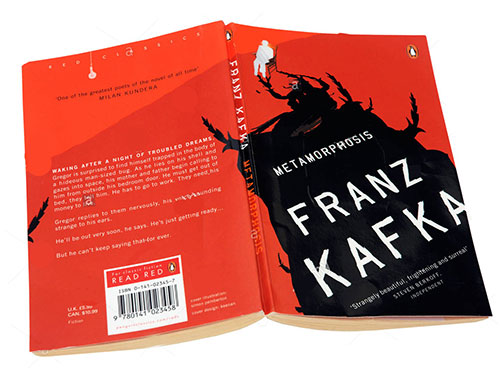

In his popular novella, titled The Metamorphosis, the Czech writer, Franz Kafka [1883 – 1924], uses his extraordinary imaginative power in the metaphorical presentation of the growth [and in contrast, the regression] of individual members of a family in crisis. The metaphor[s], drawn from nature, are carried beyond the bounds of reality into a realm of fantasy; not ignoring its human presence.

Written in German, the worldwide reception of The Metamorphosis began with its translations into several European languages after the author’s death. Despite its bizarre content, the poignancy of the tale appears to have led to its universal and lasting appeal, attracting the attention of playwrights, film-makers, music composers, psychologists and psychiatrists alike. Contemporary German educationists, inspired by its creativity and originality, included the text in the school curriculum.

Author and his Inspiration

They were troubled times with a conflict in the Balkans, the harbingers of the First World War, which broke out two years later. Despite the worldwide political instability, it was a time when literary activity flourished.

Plot Summary

“When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous insect. He lay on his back, which was as hard as an armour plate and saw as he raised his head a little, his vaulted brown belly divided by stiff, arch-shaped ribs, and the bed covers which could hardly cling to its height and were about to slide off completely. His many legs, pitifully thin compared with the rest of his bulk, waved about helplessly before his eyes.”

Gregor was a commercial traveller, living with his ageing parents [Herr and Frau Samsa] and his teenage sister [Grete]. “What an exhausting job I’ve chosen! On the move day in and day out. Business worries … and on top of that I’m saddled with the strain of all this travelling, the anxiety about train connections, the bad and irregular meals, the constant stream of changing faces with no chance of any warmer, lasting relationship. The devil takes it all!” He felt ‘condemned to work for a firm where the slightest lapse immediately gave rise to the gravest suspicion … and instant dismissal.’

Gregor mulled over quitting his job, but had to keep working to financially support his family, maintain the comfortable apartment he provided them with and to pay off his father’s debts. Regardless of the considerable expense involved, he also had plans to send his sister to the Conservatory, the following year, to train as a violinist.

Having failed in his business five years previously, Herr Samsa has been languishing at home, with no savings in hand. ‘His sister… who at 17 was still no more than a child and whose mode of life … consisting of wearing pretty clothes, sleeping late, helping in the house, indulging in a few modest amusements and above all playing the violin.’ ‘His parents did not understand the situation too well; in the course of the years they have formed the conviction that Gregor was secure in his firm for life, and besides, they were so preoccupied just now with their immediate worries that they had lost all power to look ahead.’

Since his transformation, Gregor withdrew to the dark confines of his room, ‘crawling’ around and eavesdropping on the muted conversations of his family, and retreating to his resting place under the sofa. In trying to cope with Gregor’s ‘new life’, his mother often became distraught, his father increasingly resentful, and his sister making an attempt at providing him with nourishment which was hardly palatable. With the ongoing ‘torment at home’ and the ensuing feeling of ‘helplessness’, the situation came to a head when the father displaced his anger onto Gregor by throwing apples at him. One of the apples became embedded in his back and caused the area around it to fester!!

With murmurings between father, mother and sister about the need to ‘get rid’ of the ‘monster’ that had entered their household, they began addressing the financial challenges the family was faced with. Herr Samsa takes up a job as a messenger in a bank. Frau Samsa works from home for a fashion store as a seamstress. Grete, who has taken a job as a sales-girl, starts learning shorthand and French in the evenings in the hope of bettering herself later on in life. To complement their income, they take on three lodgers and accommodate them in Grete’s room while she occupies a corner of the common room. They dismiss their house maid and employ a part-time charwoman. The robust charwoman, intolerant of the ‘balls of dust and filth’ Gregor was crawling about in, calls him, in jest, ‘a dung beetle’, drawing our attention to a metaphor!

Gregor continued to waste away. One early morning,‘ … his head sank fully down, of its own accord, and his last faint breath ebbed out of his nostrils.’ The charwoman, who entered the room, yelled at the top of her voice into the darkness: “just come and look, the creature’s done for; it’s lying there dead and done for!” She took over the task of disposing off of the corpse.

‘Let these old troubles rest at last’, said his father. The bereaved discussed their prospects for the time ahead, which were by no means bad: all three of them had jobs. They planned to move into a smaller and cheaper residence, better placed and more manageable, which Gregor had picked for them. The parents observed that their daughter has blossomed into a lively, pretty and shapely girl and ‘the time was ripe to find her a good husband!’

Commentary

Many of Kafka’s peers expressed their admiration of his work. Franz Werfel, spoke for other literary giants of the era, when he stated, “you have achieved something truly non-existent in literature before, that is, the use of a rounded, unique and highly realistic story to draw a universal, allegorical and ultimately tragic picture of the human condition”.

Drawing from nature, Kafka employs the notion of metamorphosis as a metaphor, and blends it into an important phenomenon in human experience, and creates a narrative with divergent outcomes – adaptive as well as maladaptive.

The term metamorphosis [meta- change; morph- form; osis- process] is applied to the process of transformation of an insect or amphibian from an immature to a mature form, in several stages. The immature tadpoles wriggle out of the spawn in murky waters, and in time develop into mature frogs ready to venture out into dry land, while a few, despite their effort, may succumb to the pressures of the journey.

The Samsa family fell into an abyss with the collapse of the father’s business. Gregor, the elder son, took on the responsibility of pulling them out of their predicament by persevering to work in a demanding job, in trying conditions and lacking any meaningful relationships, until his coping abilities were depleted. He regresses, metaphorically, into a half-insect form [‘dung beetle’] with diminutive legs, unable to crawl out of his mess.

After a period of stagnation, the family gains insight into their predicament. Grete says to her parents: ‘You must just try to get rid of the idea that it’s Gregor. That’s our real disaster, the fact that we’ve believed it for so long. But how can it be Gregor? If it were Gregor, he would have realised long since that it isn’t possible for human beings to live together with a creature like that, and he would have gone away of his own accord. Then we wouldn’t have a brother, but we’d be able to go on living and honour his memory.’

Grete and her parents, in an attempt at relinquishing their dependence on Gregor, first make minor adjustments within their household to improve their financial situation, before taking up employment, and moving out into more appropriate accommodation. The parents notice a shift in the fortitude of their daughter with hopes for a better future for her.

Gregor, in contrast, unable to carry the burden of his existence, sadly regresses into a primitive form with loss of mobility and unintelligible speech. He became increasingly vulnerable and dislocated from human company, leading to his demise.

An Epilogue

In a sequel to The Metamorphosis the Prager Tagblatt [Prague Tablet, June 1916] newspaper published ‘The Retransformation of Gregor Samsa’ by Karl Brand, a young, relatively unknown expressionist writer, who reportedly was disturbed by the obvious parallels between his life and that of Gregor Samsa. In his short story [which I have not had access to] Gregor is said to have risen from the ‘rubbish heap’, and after recognising his true identity, had moved to the city, with hopes of a better future!!

The latter theme is in keeping with the archetypal pattern of ‘separation-individuation’, seen in adolescence and young adulthood, as postulated by the Hungarian psychiatrist, Margaret Mahler. It is a process of change [a metamorphosis!] resulting in the movement of a young person from parental structure into developing his/her own unique identity and independence.

Such archetypal themes are part of the ‘psychological heritage’ of our common humanity, with parallel plots in the folklore of all cultures, including our own – the primordial mythical tale of the origin of the Sinhala race, brilliantly dramatised by Ediriweera Sarachchandra as ‘Sinhabahu’. The young Sinhabahu, trapped in a cave in the forest domain of his controlling yet loving father, the Lion King, breaks open the cave in his quest for individuation, carrying his mother and sister on his shoulders – a task young Gregor failed to perform.

[sirigalhenage@gmail.com]