Midweek Review

POPULAR FRONT EXPERIMENT OF 1970s IN SRI LANKA and SOUTH AMERICA

REAR VISION

By Jayantha Somasundaram

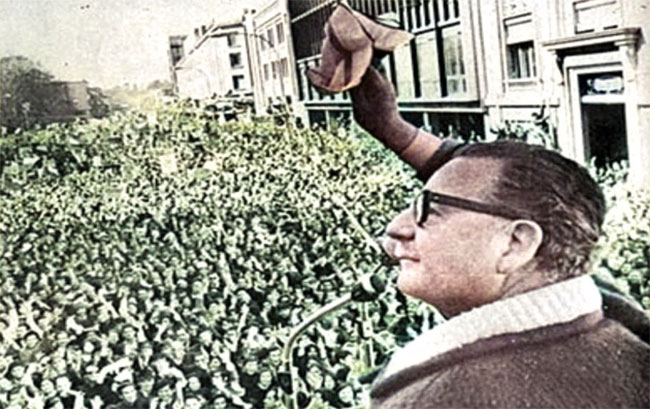

In South America the Chilean Left came together in October 1969 in the run-up to the forthcoming Presidential Election to form a multi-party front. The Unidad Popular (Popular Unity) under the leadership of Salvador Allende included among others, the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, the Radical Party, the Christian Left and the Social Democratic Party. At the 4th September 1970 Election Dr Allende obtained the largest number of votes. But since he failed to secure 50% of the popular vote, the National Congress (Parliament) had to decide between the two front runners for the presidency, Dr Allende and Jorge Alessandri.

US corporate holdings in Chile amounted to a billion dollars, half of this being in mining and smelting. Out of the over hundred US businesses in Chile, the copper companies Kennecott and Anaconda were the largest. The US also had major interests in utilities, Boise Cascade in electricity, and International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) in telecommunications.

The US was concerned about the prospect of an Allende victory in Chile. The Paris Le Monde (27 Sept) said that “in Washington the talk is that Chile has become his (President Richard Nixon’s) main preoccupation.” While a New York Times (19 Sept) editorial argued that if Dr Allende moved towards “purging the judiciary, politicising the schools or cancelling elections, then Chile’s armed forces would have a legitimate excuse for intervening.”

However, the commander of the Chilean Army was General Rene Schneider, he was adamant about military-political mutual exclusivity. The Schneider Doctrine rejected the legitimacy of a military coup, but on 22nd October he was assassinated by soldiers. “Schneider’s assassination was evidently intended to provoke the army into a coup that would prevent Allende from assuming office,” said Intercontinental Press (2 Nov 1970). Washington’s hand was suspected and in 2001 Schneider’s family accused Henry Kissinger who had been US Secretary of State at the time of the assassination, and sued him.

ITT & CIA

US columnist Jack Anderson, considered one of the giants of modern investigative journalism and winner of the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, wrote on 21 March 1972: “Secret documents which escaped shredding by ITT show that the company manoeuvred at the highest levels to stop the election of President Allende … ITT dealt regularly with the CIA (US Central Intelligence Agency) and considered triggering a military coup to head off Allende’s election … They were plotting together to create economic chaos in Chile, hoping that would cause the Chilean Army to pull a coup that would block Allende from coming to power.” Among those involved was ITT Director John McCone, a former Director of the CIA. ITT was driven by the fear of losing control over the Chile Telephone Company which Juan de Onis of The New York Times (24 March 1972) claimed “was one of the biggest earners … earning over 410 million (dollars) a year.”

That year, Anderson was targeted for assassination by the White House. The Washington Post (28 July 2004) reported that two Nixon administration conspirators had admitted under oath that they plotted to poison Anderson on orders from senior White House aide Charles Colson.

On 24 October Congress voted 153 to 35 in favour of Allende confirming him as President of Chile, which had a distinguished record as a democracy going back 120 years.

On taking office, Allende began to implement his key reforms. With regard to the economy, there was the nationalisation of the copper industries and the banking sector. In respect of property ownership there was the expansion of land reform begun by his predecessor President Eduardo Frei and that involved nationalisation of individual holdings over 200 acres.

REFORMS BEAR FRUIT

Minimum wage rates for all workers including apprentices, price controls for staples like bread, the construction of 120,000 houses and social security entitlements for all part-time workers were among the other reforms.

That political experiment was unprecedented. Allende and the left wing of the Unidad Popular (UP) to improve the standard of living of working families, both urban and rural, and achieve those reforms through parliament. Allende did not regard his government as socialist; that was only a future goal. But he earned the wrath of the establishment by recognising Cuba, nationalising foreign (mainly US) investments in Chile, extensive land reform, substantially raising wages and providing asylum to left-wing exiles from across Latin America.

At Municipal elections held in April 1971 the UP polled an increased number of votes, almost fifty percent. Allende’s January reforms, particularly those that benefited the most disadvantaged social layers, were bearing fruit. In the first year, inflation fell from 36 to 22 percent while real wages rose by 22 percent with the lowest income levels receiving a fifty percent wage hike, declining to about twenty five percent for better paid workers. In addition family allowances doubled and school supplies were being provided free. The prices of consumer goods were capped by the new regime.

Pablo Neruda the Chilean poet, who served as Chilean Consul in Ceylon in 1930. Living in Wellawatte, befriended the artists who would become the Colombo ’43 Group. Neruda, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971, told Le Monde (23 October) “There’s no reason at all to be uneasy. We have never claimed that we would form a socialist government.”

SRI LANKA’S UNITED FRONT

Emphasising the distinction Peter Camejo in The Militant (6 August) wrote “A socialist revolution in Chile would begin like the Cuban Revolution.” In the same article, Peter Camejo draws a parallel with Sri Lanka. “Ceylon is a current example of a popular front government – and one moreover, in which the Communist Party is participating …Yet, in 1971, the Ceylonese “people’s’ government” is receiving US helicopters and military aid from other imperialist powers in its ferocious campaign to suppress its own people.”

In May 1970, the United Front (UF) comprising the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) and the Communist Party (CP) won the parliamentary elections and took office. The balance of forces within the UF was radically different from the UP; the two Left parties were in the minority and in previous years had moved to the right in order to enable their coalition with the SLFP. The resulting void provided the political space for the emergence in 1965 of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (Peoples’ Liberation Front) with its claim to be the authentic left.

As in Chile, Washington was initially apprehensive about the influence of the left parties on government policy after 1970, and concerned about US economic and geostrategic interests. The April 1971 JVP insurrection however radically eroded the influence of the left in government to the extent that the Police, with no evidence, arrested LSSP MP Vasudeva Nanayakkara, who was held in custody for many months as an insurgent. The repression of the people Peter Camejo refers to was what was experienced in the wake of this insurrection.

In 1975 Felix Dias Minister of Justice, Public Administration, Local Government and Home Affairs made an official visit to Iran. This enabled him, accompanied by a Sri Lanka Overseas Service Officer, to clandestinely meet Richard Helms, US Ambassador in Iran. Until 1973 Helms had been Director of the CIA.

The UF broke up and the LSSP and CP left the government. The UF had previously been committed to an economy where the government would be the driving force. But with the expulsion of the LSSP and CP there was a radical reversal of policy, and the move to a free-market economy. This did not prevent the SLFP being badly defeated at the 1977 General Election, and the subsequent entrenchment of free-market policies by Jayewardene’s United National Party.

(To be continued)