Features

Old order changing

by Rajiva Wijesinha

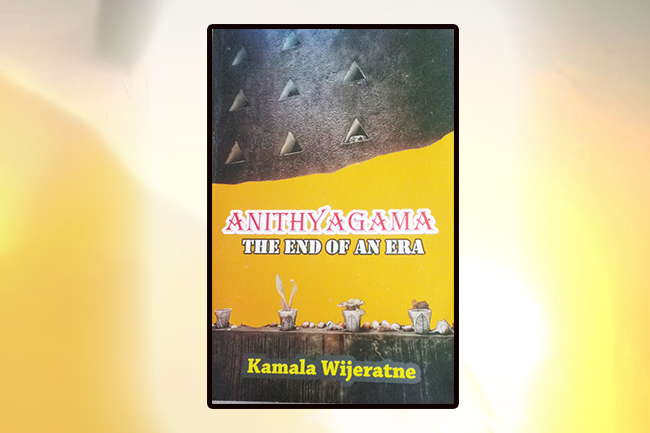

Kamala Wijeratne’s second novel, which was launched last month, is another impressive achievement by a writer who first made her mark as a poet. Anithyagama: the end of an era looks at the ethnic conflict, as her last novel An Untold Story did, but its predominant subject is the decline of a walauwe. The protagonist is a girl who had been brought up there by her grandmother and her aunts after her mother had died, though she was packed off to her father when she got involved with the son of a woman who worked in the walauwe.

She had associated closely with Sirisoma, who had won a scholarship to a good school, when she was studying for her Advanced Levels, but the disruption of her life when their romance was discovered put paid to her studies, and she became a teacher, working first in government service in a remote Tamil school. There she is helped by a fellow teacher with whom she falls in love when she comes across him again in Colombo when she is finally at university for a postgraduate course.

He is in love with her too, but this does not stop him using her in his work for the LTTE, and he comes to her for shelter when he is sought by the forces after a bomb blast which he was responsible for. She helps him, and to get away to Canada, but when he asks her to join him, she refuses. He had told her that his whole family was bitter after his younger brother had been killed during the July 1983 riots, and she felt that he would not have peace from them if he married her.

She never sees him again, but she does meet her first love when she goes back to the walauwe when her last aunt dies. He is now a senior public servant, and very rich, and in fact he buys the place from her brother who had inherited it. He is in Australia, and does not come back for the funeral, but returns for the three month almsgiving and finalizes the sale then.

That saddens her, but she has reconciled herself to the fact that as a girl she has no say in the matter. Her aunt had not thought twice about leaving the property to her nephew, though he was an academic and doing well whereas his twin sister had greater need of financial support.

But, though Suseema’s personal story is interesting, the more important subject of the novel was Rathmalwala Walauwe where she had grown up, and where her younger aunt lived alone for several years, before her death that set the novel in motion.

Or rather she had not lived alone, for with her was Dingiri Amma, who had been brought up by her mother, as a privileged servant who ran the place as the old lady got frailer. And there was also still a support system of sorts, for one tenant farmer still felt he had feudal obligations, and indeed he and his son did yeoman service for the funeral and the almsgivings.

Kudamma did not in fact live in the whole walauwe, but only in half of it, for her brother had got the other half. He was dead and his son lived there now, but there was no contact with his aunt for he had married someone deemed unsuitable. Suseema was content for this alienation to continue, but her brother Sumitta, back for the three month almsgiving, insisted on asking his cousin.

Kamala Wijeratne makes clear that the ostracization was general, on the part of other members of the family, while the critique of Sirisoma and also of his mother by the other walauwe servants is scathing. But her brother demands tolerance there too, recalling how Sirisoma’s father had looked after their grandparents when they were helpless.

There is much about old customs, and the excessive cooking that is required during funerals and almsgivings, much about the old photographs interspersed with pictures of the Royal Family, much about the land the walauwe had which has diminished. Kamala Wijeratne also introduces the lingering of the old lady’s spirit which is seen by both Suseema and one of the staff. But after all the almsgivings, the spirit seems to have been assuaged and does not appear again.

Juxtaposed with this evocation of past shades is the account of Suseema’s main preoccupation at her school during this period, training her girls for a drama competition. They are enacting scenes from Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, also about a feudal family in decline. It ends with an old retainer regretting the sound of cherry trees being cut down, which blends in Suseema’s mind with the clove trees in the garden which she knows are also doomed.

The novel is replete with telling scenes, the different reactions of tenant farmers after the Paddy Lands Act gave them major rights over the land they cultivated, the vulgarity of the house that Sirisoma had built, with Japanese tiles, that reminded Suseema of the Great Gatsby, the molesting of Dingiri Amma, probably by Suseema’s uncle.

In the end Suseema takes Dingiri Amma away with her, to keep in the little annexe she rents in Colombo, where she cooks her meals and makes her Milo. But as we think of her life, and its lost opportunities, we are reminded of others, for there is brief mention of a cousin of the dead Kudamma whom she had not been permitted to marry, given consanguinity. The novel as a whole is a remarkable achievement, capturing so many elements in life and a changing society so economically and effectively.