Features

Not a deterrent against crime

Death penalty again in focus (Part II)

BY Dr Jayampathy Wickramaratne

President’s Counsel

The committee appointed by the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Human Rights to draft a new fundamental rights chapter for the Constitution that accords with Sri Lanka’s international obligations recommended the abolition of the death penalty in its report submitted in November 2009.

The committee stated that it was not unmindful of public concerns that the crime rate in Sri Lanka is on the increase and that some persons convicted of grave crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment or long terms come out of prison quite early. The solution to this is judicial control of parole. It recommended that in respect of those who are sentenced to long periods of imprisonment, legal provision should be made for the sentencing judge to make an order that the offender’s term of imprisonment should not be reduced unless authorised by the court in the circumstances and manner and to the extent provided by law.

The committee noted that no person had been executed in Sri Lanka since 1975 and that in both 2007 and 2008, Sri Lanka voted at the United Nations in favour of resolutions calling for a moratorium on executions as a step towards the ultimate abolition of the death penalty. The 2007 resolution referred to, which was affirmed in 2008, declared ‘[t]hat the use of the death penalty undermines human dignity, and convinced that a moratorium on the use of the death penalty contributes to the enhancement and progressive development of human rights, that there is no conclusive evidence of the deterrent value of the death penalty and that any miscarriage or failure of justice in the implementation of the death penalty is irreversible and irreparable.’

Sri Lanka voted again in 2010 in favour of a moratorium on the death penalty but abstained in 2012 and 2014 during the second term of President Mahinda Rajapaksa. Sri Lanka again voted in favour in 2016 and 2018. The ‘yes’ vote has been increasing consistently. In 2018, 121 out of the 193 member states voted ‘yes’, 35 opposing, and 32 abstaining. The 2020 vote was 123 in favour, 38 votes against, 24 countries abstaining and eight absent. On 15 December 2022, the General Assembly adopted the ninth resolution for a moratorium with 125 votes in favour (2 more than in 2020), 37 votes against, 22 abstentions and nine absent. Sri Lanka voted in favour both in 2020 and 2022.

Is the death penalty a deterrent?

One of the most common arguments in favour of the death penalty is that it is a deterrent against serious crime. If that is the case, serious crime figures in jurisdictions with the death penalty should be lower than in those that do not have the death penalty.

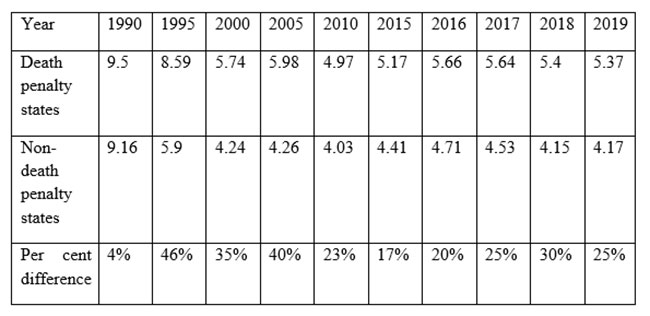

Not all states in the United States have the death penalty. Murder rates in death penalty states and non-death penalty states show unmistakably that the death penalty is not a deterrent at all. The following table giving murder rates has been prepared based on the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports and published on the website of the Death Penalty Information Centre (https://deathpenaltyinfo.org). Murder rates have been calculated by dividing the number of murders by the total population in the death penalty and non-death penalty states, respectively and multiplying that by 100,000. (See Table)

A poll of 500 Police chiefs in the United States was conducted in 2008 by R.T. Strategies of Washington, DC. When asked to name one area as ‘most important for reducing violent crime’, Police chiefs ranked the death penalty last. They considered issues such as increasing the number of police officers, reducing drug abuse, and creating a better economy as higher priorities.

Michael L. Radelet, Chair Professor of Sociology at the University of Colorado-Boulder, in his 2009 article ‘Do Executions Lower Homicide Rates?: The Views of Leading Criminologists’ published in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, stated:

‘Our survey indicates that the vast majority of the world’s top criminologists believe that the empirical research has revealed the deterrence hypothesis for a myth. … 88.2% of polled criminologists do not believe that the death penalty is a deterrent. … 9.2% answered that the statement ‘[t]he death penalty significantly reduces the number of homicides’ was accurate. … Overall, it is clear that however measured, fewer than 10% of the polled experts believe the deterrence effect of the death penalty is stronger than that of long-term imprisonment. … Recent econometric studies, which posit that the death penalty has a marginal deterrent effect beyond that of long-term imprisonment, are so limited or flawed that they have failed to undermine consensus. In short, the consensus among criminologists is that the death penalty does not add any significant deterrent effect above that of long-term imprisonment.’

Justice Thurgood Marshall, in his concurrent opinion in the landmark US case of Furman v. Georgia, stated: ‘It is generally agreed between the retentionists and abolitionists, whatever their opinions about the validity of comparative studies of deterrence, that the data which now exist show no correlation between the existence of capital punishment and lower rates of capital crime. Despite the fact that abolitionists have not proved non-deterrence beyond a reasonable doubt, they have succeeded in showing by clear and convincing evidence that capital punishment is not necessary as a deterrent to crime in our society.

In light of the massive amount of evidence before us, I see no alternative but to conclude that capital punishment cannot be justified on the basis of its deterrent effect.’

Lee Sarokin, a former US Court of Appeals Judge, says in his 2011 article ‘Is It Time to Execute the Death Penalty?’ published on the Huffington Post website: ‘In my view, deterrence plays no part whatsoever. Persons contemplating murder do not sit around the kitchen table and say I won’t commit this murder if I face the death penalty, but I will do it if the penalty is life without parole. I do not believe persons contemplating or committing murder plan to get caught or weigh the consequences. Statistics demonstrate that states without the death penalty have consistently lower murder rates than states with it, but frankly, I think those statistics are immaterial and coincidental. Fear of the death penalty may cause a few to hesitate, but certainly not enough to keep it in force.’

It is clear from the above that the most effective deterrent against serious crime is an effective criminal justice system. A person who knows that the chances of a crime being properly investigated and successfully prosecuted, and the culprit given a proportionate punishment are high, s/he would hesitate to commit it.

The writer wishes to conclude this article with an anecdote. The issue of reinstating the death penalty came up for discussion in the second term of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, with several Ministers also speaking in favour. Concerned by these reports, several persons suggested that I ‘counsel’ President Kumaratunga on the issue. I met the President, armed with facts and figures. I was barely into my second sentence when she cut me short, ending my shortest conversation with her on any subject, saying: ‘Anybody can suggest, but it is I who has to sign the warrant of execution. I will never do that.’ This was a person whose father and husband were both assassinated and whom herself had narrowly escaped assassination while losing one eye.