Opinion

Navigating course of education reforms in SL: Past challenges and future directions

by Prof. M.W. Amarasiri de Silva

The government has proposed abolishing the University Grants Commission (UGC) set up under the Universities Act No. 16 of 1978 and replacing it with an independent body called the “National Higher Education Commission.” This change is set to be enacted through new legislation. As the Chairman of the Select Committee, Minister Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe has recommended the National Higher Education Commission will consist of 11 members appointed by the President, subject to prior approval from the Constitutional Council. These members are expected to be eminent individuals in their respective fields, including academia, profession, and management. Accordingly, the proposed Commission will be organized into four sub-committees: the State University Committee, the Non-State University Committee, the Vocational Education Institutions Committee, and a sub-committee dedicated to quality assurance. Each sub-committee will focus on specific aspects of higher education in the country. Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, PC, emphasized that opportunities for higher education should be expanded to match the labour market.

In implementing the proposed reforms, it is crucial to take into consideration the existence of various government-formed institutions that have been dealing with different aspects of education over the years. The new proposal, as published in the newspapers, lacks specific information on how these institutions will be addressed and what changes they might undergo. One important institution to consider is the National Institute of Education (NIE), which was established in 1985 through an Act of Parliament. The NIE was entrusted with the vital tasks of curriculum development and awarding degrees in education to support the professional development of teachers, principals, and educational administrators. However, the proposal does not clarify how the new curriculum development committee will impact the role and functions of the NIE.

Similarly, the formulation of the national education policy relies on the recommendations provided by the National Education Commission (NEC), which was established in 1991 through an Act of Parliament. The NEC holds a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s education policy. Yet, it remains uncertain how the proposed reforms will affect the NEC’s position and functions.

Another significant institution is the Curriculum Development Centre (CDC), established in the 1960s. Initially focused on developing curricula for science and mathematics, the CDC has evolved over time to encompass curricula development across all subjects and has contributed to teacher development efforts. It is essential to address the potential impact of the new proposals on the CDC and its continuing role in education reform.

To ensure the success of the proposed reforms, it is imperative that the fate and functions of these existing institutions are explicitly addressed and aligned with the broader vision of the educational changes being proposed. Clarity on their roles and potential restructuring will help in achieving a more cohesive and effective education system in the country.

Why can these changes not be implemented within the structure of the University Grant Commission and the institutions setup to deal with various aspects of education in the country? This article reviewing the history of education reforms in Sri Lanka tries to answer these questions.

Sri Lanka’s history of education reforms has been marked by the establishment of various committees and programs proposed by successive governments over the years. In 1975-76, the government made a significant effort to further strengthen its control over the universities through amendments to the University of Ceylon Act No. 1 of 1972. These proposed amendments aimed to increase the government’s authority over the universities, much like the recently proposed reforms by the Minister of Higher Education.

However, the introduction of these amendments faced opposition from the universities and students, who were concerned about the concentration of powers in the hands of the government. The proposed amendments had to be withdrawn in response to widespread trade union actions and dissent.

The political landscape shifted in 1997, with the opposition party winning the election. They made a crucial pledge to grant autonomy to individual universities, and this promise was championed by Ronnie de Mel and the United National Party (UNP).

These historical episodes illustrate the ongoing struggle to balance government influence and university autonomy in Sri Lanka’s higher education system. The currently proposed reforms should consider these past experiences to ensure a harmonious and practical approach to shaping the future of education in the country. Acknowledging the crucial role of education in the country’s development, the ministers of higher education have consistently sought to reshape the higher education landscape, even though the universities were considered autonomous institutions according to the Universities Act, No. 16 of 1978. This emphasis on education reform arises from the belief that a robust and dynamic education system, encompassing both school and university education, is indispensable for propelling the nation’s progress and prosperity. As such, it becomes the government’s prerogative to introduce changes to achieve this goal.

The most pivotal and ground-breaking reform that laid the foundation for Sri Lanka’s free education system was the comprehensive overhaul of the educational framework in 1945. This transformative reform was built upon the principles outlined in the Education Ordinance No. 31 of 1939, making it the foremost and all-encompassing reform ever undertaken in the country’s educational history. During this period, C.W.W. Kannangara, who held the education portfolio in the State Council from 1931 to 1947, played a crucial role with A. Ratnayake in revolutionizing the education system.

The education reforms of 1945 brought about significant changes—the reforms aimed to provide free education from kindergarten up to university level. Swabhasha (Sinhala and Tamil) was established as the primary medium of instruction in schools, while English continued to have its place as a language taught from Standard III onwards. This emphasis on both languages sought to strike a balance between preserving the country’s cultural identity and enabling students to engage with a globalised world.

Most significantly, these reforms opened opportunities for children from rural areas and less privileged backgrounds to access education. Central Colleges, established by the government, played a crucial role in this process by providing accessible education to village children, enabling them to climb the social ladder through learning and knowledge.

In contemporary times, the history of university education in Sri Lanka spans just over a few decades. From 1921 to 1959, the country had only one educational institution offering university-level education, University College (1921–1942), affiliated with the University of London. In 1942, following 21 years of agitation, the University of Ceylon was finally established at Peradeniya. Subsequently, in 1959, the education landscape underwent a significant transformation with the establishment of two additional universities – Vidyalankara and Vidyodaya- the two main centres of Buddhist learning in Ceylon were swiftly converted into universities. This expansion led to recognising the necessity for a coordinating body to oversee higher education activities. In 1966, the National Council of Higher Education (NCHE) was established as a part of a policy to increase government influence over universities.

In 1979, the University Grants Commission (UGC) was established, equipped with powers akin to the National Council of Higher Education (NCHE). However, the UGC’s authority extended even further, surpassing the scope enjoyed by the British UGC. Notably, Professor S. Kalpage, a highly experienced university teacher with a diverse academic background, was appointed as the inaugural chairman of the UGC. Interestingly, he also held the position of Secretary of the Ministry of Higher Education.

The appointment of Professor S. Kalpage as the first chairman of the UGC was a strategic decision by the government, aimed at avoiding potential conflicts between the Ministry of Higher Education and the newly formed UGC during its initial developmental years. This move demonstrated the government’s proactive approach to ensure a harmonious working relationship between these entities and facilitate a smooth and effective implementation of the UGC’s role in shaping higher education in the country.

In 2016, G.B. Gunawardene, the National Education Commission (NEC) chairman, pointed out that the 1939 Rathnayaka-Kannangara Education Ordinance (No. 31 of 1939) remains the foundational law of education in Sri Lanka. Despite several subsequent acts introduced for different aspects of education, there have been no meaningful amendments or changes to the core education law. Dr. Gunawardene emphasized the need for an education policy framework rather than new acts to address the challenges and requirements of the modern education system.

Regarding the possibility of a new act, it’s essential to clarify that introducing a new law does not necessarily mean the 1939 act would be annulled. The new act could be complementary, addressing specific areas or aspects of education that may require updated regulations. However, the 1939 act would remain the foundation and overarching framework for education in the country unless it is explicitly repealed or replaced.

The national university of Ceylon was started in 1942, and no particular administrative unit was within that ministry to deal with the university. The only formal link was provided by one of the officials of the ministry, the director of education, who was the principal administrative officer in control of primary and secondary education in the country’s state education sector, and an ex officio member of the council, the university’s governing body.

The significant shift and political interventions in university education occurred following the formation of the 1956 government and its political interventions. This period witnessed notable changes, including an increase in student enrolment, particularly in the arts and social sciences fields. Moreover, there was a shift in the medium of instruction from English to Sinhalese and Tamil, a move perceived as an apolitical endeavour for social justice.

However, this new approach diverged from the vision of the Kannangara-Ratnayake reforms, which aimed to strike a balance by using English as the language of instruction from the 3rd standard while promoting the use of swabhasha (Sinhala and Tamil) as the medium of instruction. The introduction of the new system marked a departure from the previous reform’s principles.

The historical context of education reforms in Sri Lanka dates to the era of IMRA Iriyagolla, during which the higher education system experienced significant upheaval. Although the specific details of the havoc caused during that time are not mentioned, it serves as a reminder that changes in the education sector have not always been smooth and have sometimes encountered challenges and controversies.

Subsequently, in response to the need for comprehensive administration and oversight of the country’s universities, the idea of establishing the University Grants Commission (UGC) emerged. The idea was mooted when Premadasa Udagama, Secretary of Education and the Director General of the Ministry of Education from 1970 to 1977. The UGC aimed to unify all universities under one administrative umbrella, streamlining processes and enhancing coordination among the higher education institutions. Establishing the UGC marked a significant step forward in Sri Lanka’s efforts to reform and improve the higher education system. This centralised approach sought to address various administrative and operational inefficiencies that might have hindered the optimal growth and development of universities. Through the UGC, the government aimed to ensure that universities received adequate funding, maintained high academic standards, and aligned their programmes with national development priorities. (To be continued)

Opinion

Child food poverty: A prowling menace

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin),

FRCP(Lon), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow,

Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health

In an age of unprecedented global development, technological advancements, universal connectivity, and improvements in living standards in many areas of the world, it is a very dark irony that child food poverty remains a pressing issue. UNICEF defines child food poverty as children’s inability to access and consume a nutritious and diverse diet in early childhood. Despite the planet Earth’s undisputed capacity to produce enough food to nourish everyone, millions of children still go hungry each day. We desperately need to explore the multifaceted deleterious effects of child food poverty, on physical health, cognitive development, emotional well-being, and societal impacts and then try to formulate a road map to alleviate its deleterious effects.

Every day, right across the world, millions of parents and families are struggling to provide nutritious and diverse foods that young children desperately need to reach their full potential. Growing inequities, conflict, and climate crises, combined with rising food prices, the overabundance of unhealthy foods, harmful food marketing strategies and poor child-feeding practices, are condemning millions of children to child food poverty.

In a communique dated 06th June 2024, UNICEF reports that globally, 1 in 4 children; approximately 181 million under the age of five, live in severe child food poverty, defined as consuming at most, two of eight food groups in early childhood. These children are up to 50 per cent more likely to suffer from life-threatening malnutrition. Child Food Poverty: Nutrition Deprivation in Early Childhood – the third issue of UNICEF’s flagship Child Nutrition Report – highlights that millions of young children are unable to access and consume the nutritious and diverse diets that are essential for their growth and development in early childhood and beyond.

It is highlighted in the report that four out of five children experiencing severe child food poverty are fed only breastmilk or just some other milk and/or a starchy staple, such as maize, rice or wheat. Less than 10 per cent of these children are fed fruits and vegetables and less than 5 per cent are fed nutrient-dense foods such as eggs, fish, poultry, or meat. These are horrendous statistics that should pull at the heartstrings of the discerning populace of this world.

The report also identifies the drivers of child food poverty. Strikingly, though 46 per cent of all cases of severe child food poverty are among poor households where income poverty is likely to be a major driver, 54 per cent live in relatively wealthier households, among whom poor food environments and feeding practices are the main drivers of food poverty in early childhood.

One of the most immediate and visible effects of child food poverty is its detrimental impact on physical health. Malnutrition, which can result from both insufficient calorie intake and lack of essential nutrients, is a prevalent consequence. Chronic undernourishment during formative years leads to stunted growth, weakened immune systems, and increased susceptibility to infections and diseases. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition are more likely to suffer from conditions such as anaemia, rickets, and developmental delays.

Moreover, the lack of proper nutrition can have long-term health consequences. Malnourished children are at a higher risk of developing chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity later in life. The paradox of child food poverty is that it can lead to both undernutrition and overnutrition, with children in food-insecure households often consuming calorie-dense but nutrient-poor foods due to economic constraints. This dietary pattern increases the risk of obesity, creating a vicious cycle of poor health outcomes.

The impacts of child food poverty extend beyond physical health, severely affecting cognitive development and educational attainment. Adequate nutrition is crucial for brain development, particularly in the early years of life. Malnutrition can impair cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and problem-solving skills. Studies have consistently shown that malnourished children perform worse academically compared to their well-nourished peers. Inadequate nutrition during early childhood can lead to reduced school readiness and lower IQ scores. These children often struggle to concentrate in school, miss more days due to illness, and have lower overall academic performance. This educational disadvantage perpetuates the cycle of poverty, as lower educational attainment reduces future employment opportunities and earning potential.

The emotional and psychological effects of child food poverty are profound and are often overlooked. Food insecurity creates a constant state of stress and anxiety for both children and their families. The uncertainty of not knowing when or where the next meal will come from can lead to feelings of helplessness and despair. Children in food-insecure households are more likely to experience behavioural problems, including hyperactivity, aggression, and withdrawal. The stigma associated with poverty and hunger can further exacerbate these emotional challenges. Children who experience food poverty may feel shame and embarrassment, leading to social isolation and reduced self-esteem. This psychological toll can have lasting effects, contributing to mental health issues such as depression and anxiety in adolescence and adulthood.

Child food poverty also perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality. Children who grow up in food-insecure households are more likely to remain in poverty as adults, continuing the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage. This cycle of poverty exacerbates social disparities, contributing to increased crime rates, reduced social cohesion, and greater reliance on social welfare programmes. The repercussions of child food poverty ripple through society, creating economic and social challenges that affect everyone. The healthcare costs associated with treating malnutrition-related illnesses and chronic diseases are substantial. Additionally, the educational deficits linked to child food poverty result in a less skilled workforce, which hampers economic growth and productivity.

Addressing child food poverty requires a multi-faceted approach that tackles both immediate needs and underlying causes. Policy interventions are crucial in ensuring that all children have access to adequate nutrition. This can include expanding social safety nets, such as food assistance programmes and school meal initiatives, as well as targeted manoeuvres to reach more vulnerable families. Ensuring that these programmes are adequately funded and effectively implemented is essential for their success.

In addition to direct food assistance, broader economic and social policies are needed to address the root causes of poverty. This includes efforts to increase household incomes through living wage policies, job training programs, and economic development initiatives. Supporting families with affordable childcare, healthcare, and housing can also alleviate some of the financial pressures that contribute to food insecurity.

Community-based initiatives play a vital role in combating child food poverty. Local food banks, community gardens, and nutrition education programmes can help provide immediate relief and promote long-term food security. Collaborative efforts between government, non-profits, and the private sector are necessary to create sustainable solutions.

Child food poverty is a profound and inescapable issue with far-reaching consequences. Its deleterious effects on physical health, cognitive development, emotional well-being, and societal stability underscore the urgent need for comprehensive action. As we strive for a more equitable and just world, addressing child food poverty must be a priority. By ensuring that all children have access to adequate nutrition, we can lay the foundation for a healthier, more prosperous future for individuals and society as a whole. The fight against child food poverty is not just a moral imperative but an investment in our collective future. Healthy, well-nourished children are more likely to grow into productive, contributing members of society. The benefits of addressing this issue extend beyond individual well-being, enhancing economic stability and social harmony. It is incumbent upon us all to recognize and act upon the understanding that every child deserves the right to adequate nutrition and the opportunity to thrive.

Despite all of these existent challenges, it is very definitely possible to end child food poverty. The world needs targeted interventions to transform food, health, and social protection systems, and also take steps to strengthen data systems to track progress in reducing child food poverty. All these manoeuvres must comprise a concerted effort towards making nutritious and diverse diets accessible and affordable to all. We need to call for child food poverty reduction to be recognized as a metric of success towards achieving global and national nutrition and development goals.

Material from UNICEF reports and AI assistance are acknowledged.

Opinion

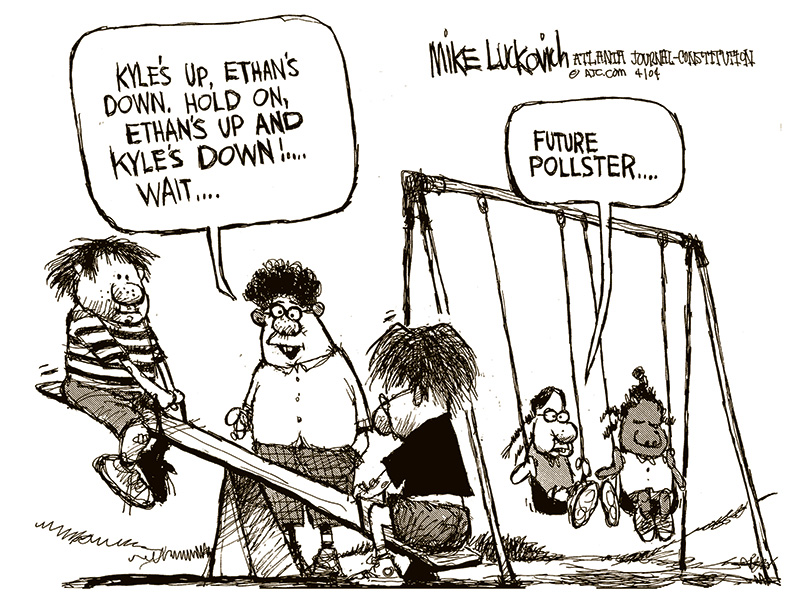

Do opinion polls matter?

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

The colossal failure of not a single opinion poll predicting accurately the result of the Indian parliamentary election, the greatest exercise in democracy in the world, raises the question whether the importance of opinion polls is vastly exaggerated. During elections two types of opinion polls are conducted; one based on intentions to vote, published during or before the campaign, often being not very accurate as these are subject to many variables but exit polls, done after the voting where a sample tally of how the voters actually voted, are mostly accurate. However, of the 15 exit polls published soon after all the votes were cast in the massive Indian election, 13 vastly overpredicted the number of seats Modi’s BJP led coalition NDA would obtain, some giving a figure as high as 400, the number Modi claimed he is aiming for. The other two polls grossly underestimated predicting a hung parliament. The actual result is that NDA passed the threshold of 272 comfortably, there being no landslide. BJP by itself was not able to cross the threshold, a significant setback for an overconfident Mody! Whether this would result in less excesses on the part of Modi, like Muslim-bashing, remains to be seen. Anyway, the statement issued by BJP that they would be investigating the reasons for failure rather than blaming the process speaks very highly of the maturity of the democratic process in India.

I was intrigued by this failure of opinion polls as this differs dramatically from opinion polls in the UK. I never failed to watch ‘Election night specials’ on BBC; as the Big Ben strikes ‘ten’ (In the UK polls close at 10pm} the anchor comes out with “Exit polls predict that …” and the actual outcome is often almost as predicted. However, many a time opinion polls conducted during the campaign have got the predictions wrong. There are many explanations for this.

An opinion poll is defined as a research survey of public opinion from a particular sample, the origin of which can be traced back to the 1824 US presidential election, when two local newspapers in North Carolina and Delaware predicted the victory of Andrew Jackson but the sample was local. First national survey was done in 1916 by the magazine, Literary Digest, partly for circulation-raising, by mailing millions of postcards and counting the returns. Of course, this was not very scientific though it accurately predicted the election of Woodrow Wilson.

Since then, opinion polls have grown in extent and complexity with scientific methodology improving the outcome of predictions not only in elections but also in market research. As a result, some of these organisations have become big businesses. For instance, YouGov, an internet-based organisation co-founded by the Iraqi-born British politician Nadim Zahawi, based in London had a revenue of 258 million GBP in 2023.

In Sri Lanka, opinion polls seem to be conducted by only one organisation which, by itself, is a disadvantage, as pooled data from surveys conducted by many are more likely to reflect the true situation. Irrespective of the degree of accuracy, politicians seem to be dependent on the available data which lend explanations to the behaviour of some.

The Institute for Health Policy’s (IHP) Sri Lanka Opinion Tracker Survey has been tracking the voting intentions for the likely candidates for the Presidential election. At one stage the NPP/JVP leader AKD was getting a figure over 50%. This together with some degree of international acceptance made the JVP behave as if they are already in power, leading to some incidents where their true colour was showing.

The comments made by a prominent member of the JVP who claimed that the JVP killed only the riff-raff, raised many questions, in addition to being a total insult to many innocents killed by them including my uncle. Do they have the authority to do so? Do extra-judicial killings continue to be JVP policy? Do they consider anyone who disagrees with them riff-raff? Will they kill them simply because they do not comply like one of my admired teachers, Dr Gladys Jayawardena who was considered riff-raff because she, as the Chairman of the State Pharmaceutical Corporation, arranged to buy drugs cheaper from India? Is it not the height of hypocrisy that AKD is now boasting of his ties to India?

Another big-wig comes with the grand idea of devolving law and order to village level. As stated very strongly, in the editorial “Pledges and reality” (The Island, 20 May) is this what they intend to do: Have JVP kangaroo-courts!

Perhaps, as a result of these incidents AKD’s ratings has dropped to 39%, according to the IHP survey done in April, and Sajith Premadasa’s ratings have increased gradually to match that. Whilst they are level pegging Ranil is far behind at 13%. Is this the reason why Ranil is getting his acolytes to propagate the idea that the best for the country is to extend his tenure by a referendum? He forced the postponement of Local Governments elections by refusing to release funds but he cannot do so for the presidential election for constitutional reasons. He is now looking for loopholes. Has he considered the distinct possibility that the referendum to extend the life of the presidency and the parliament if lost, would double the expenditure?

Unfortunately, this has been an exercise in futility and it would not be surprising if the next survey shows Ranil’s chances dropping even further! Perhaps, the best option available to Ranil is to retire gracefully, taking credit for steadying the economy and saving the country from an anarchic invasion of the parliament, rather than to leave politics in disgrace by coming third in the presidential election. Unless, of course, he is convinced that opinion polls do not matter and what matters is the ballots in the box!

Opinion

Thoughtfulness or mindfulness?

By Prof. Kirthi Tennakone

ktenna@yahoo.co.uk

Thoughtfulness is the quality of being conscious of issues that arise and considering action while seeking explanations. It facilitates finding solutions to problems and judging experiences.

Almost all human accomplishments are consequences of thoughtfulness.

Can you perform day-to-day work efficiently and effectively without being thoughtful? Obviously, no. Are there any major advancements attained without thought and contemplation? Not a single example!

Science and technology, art, music and literary compositions and religion stand conspicuously as products of thought.

Thought could have sinister motives and the only way to eliminate them is through thought itself. Thought could distinguish right from wrong.

Empathy, love, amusement, and expression of sorrow are reflections of thought.

Thought relieves worries by understanding or taking decisive action.

Despite the universal virtue of thoughtfulness, some advocate an idea termed mindfulness, claiming the benefits of nurturing this quality to shape mental wellbeing. The concept is defined as focusing attention to the present moment without judgment. A way of forgetting the worries and calming the mind – a form of meditation. A definition coined in the West to decouple the concept from religion. The attitude could have a temporary advantage as a method of softening negative feelings such as sorrow and anger. However, no man or woman can afford to be non-judgmental all the time. It is incompatible with indispensable thoughtfulness! What is the advantage of diverting attention to one thing without discernment during a few tens of minute’s meditation? The instructors of mindfulness meditation tell you to focus attention on trivial things. Whereas in thoughtfulness, you concentrate the mind on challenging issues. Sometimes arriving at groundbreaking scientific discoveries, solution of mathematical problems or the creation of masterpieces in engineering, art, or literature.

The concept of meditation and mindfulness originated in ancient India around 1000 BCE. Vedic ascetics believed the practice would lead to supernatural powers enabling disclosure of the truth. Failing to meet the said aspiration, notwithstanding so many stories in scripture, is discernable. Otherwise, the world would have been awakened to advancement by ancient Indians before the Greeks. The latter culture emphasized thoughtfulness!

In India, Buddha was the first to deviate from the Vedic philosophy. His teachers, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputra, were adherents of meditation. Unconvinced of their approach, Buddha concluded a thoughtful analysis of the actualities of life should be the path to realisation. However, in an environment dominated by Vedic tradition, meditation residually persisted when Buddha’s teachings transformed into a religion.

In the early 1970s, a few in the West picked up meditation and mindfulness. We Easterners, who criticize Western ideas all the time, got exalted after seeing something Eastern accepted in the Western circles. Thereafter, Easterners took up the subject more seriously, in the spirit of its definition in the West.

Today, mindfulness has become a marketable commodity – a thriving business spreading worldwide, fueled largely by advertising. There are practice centres, lessons onsite and online, and apps for purchase. Articles written by gurus of the field appear on the web.

What attracts people to mindfulness programmes? Many assume them being stressed and depressed needs to improve their mental capacity. In most instances, these are minor complaints and for understandable reasons, they do not seek mainstream medical interventions but go for exaggeratedly advertised alternatives. Mainstream medical treatments are based on rigorous science and spell out both the pros and cons of the procedure, avoiding overstatement. Whereas the alternative sector makes unsubstantiated claims about the efficacy and effectiveness of the treatment.

Advocates of mindfulness claim the benefits of their prescriptions have been proven scientifically. There are reports (mostly in open-access journals which charge a fee for publication) indicating that authors have found positive aspects of mindfulness or identified reasons correlating the efficacy of such activities. However, they rarely meet standards normally required for unequivocal acceptance. The gold standard of scientific scrutiny is the statistically significant reproducibility of claims.

If a mindfulness guru claims his prescription of meditation cures hypertension, he must record the blood pressure of participants before and after completion of the activity and show the blood pressure of a large percentage has stably dropped and repeat the experiment with different clients. He must also conduct sessions where he adopts another prescription (a placebo) under the same conditions and compares the results. This is not enough, he must request someone else to conduct sessions following his prescription, to rule out the influence of the personality of the instructor.

The laity unaware of the above rigid requirements, accede to purported claims of mindfulness proponents.

A few years ago, an article published and widely cited stated that the practice of mindfulness increases the gray matter density of the brain. A more recent study found there is no such correlation. Popular expositions on the subject do not refer to the latter report. Most mindfulness research published seems to have been conducted intending to prove the benefits of the practice. The hard science demands doing the opposite as well-experiments carried out intending to disprove the claims. You need to be skeptical until things are firmly established.

Despite many efforts diverted to disprove Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, no contradictions have been found in vain to date, strengthening the validity of the theory. Regarding mindfulness, as it stands, benefits can neither be proved nor disproved, to the gold standard of scientific scrutiny.

Some schools in foreign lands have accommodated mindfulness training programs hoping to develop the mental facility of students and Sri Lanka plans to follow. However, studies also reveal these exercises are ineffective or do more harm than good. Have we investigated this issue before imitation?

Should we force our children to focus attention on one single goal without judgment, even for a moment?

Why not allow young minds to roam wild in their deepest imagination and build castles in the air and encourage them to turn these fantasies into realities by nurturing their thoughtfulness?

Be more thoughtful than mindful?