Features

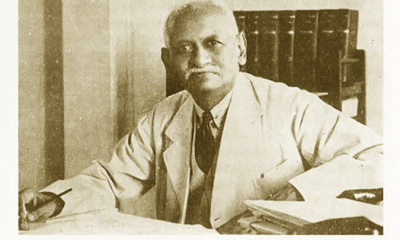

MY FATHER

by LC Arulpragasam

(This is another excerpt from the book Falling Leaves, a part autobiographical anthology of articles by one of the last remaining members of the old Ceylon Civil Service, now living in Manila at age of over 95-years. A painting my the author adorns the book cover.)

My father was Dr. Albert Rajaratnam Arulpragasam. To my regret, I do not know much about him, because he kept to himself. He was born on June 12, 1890. He died in 1957 in Jaffna. By profession, he was a medical doctor working for the government of Ceylon, retiring at the age of 60 years. After a few years in Colombo, my parents retired to their home in Chundikuli (Jaffna) – a home he inherited from his sister. I (we) do not know much about my father, mainly because he was a very private, reticent and self-effacing man, who seemed reluctant to talk about his childhood or about his past. We, his children, must also be blamed for our lack of curiosity in regard to the man who quietly and uncomplainingly provided the means for us to go to the best schools and University in Ceylon and to embark on successful careers.

This lack of knowledge also arose partly because we were all the time in boardings and schools in Colombo, whereas my father was always stationed in the provinces, so that we never got to really know him. My sister, on the other hand, who spent a longer time at home, was able to dig out more stories from our reticent father. Hence, what I record below is information that I gleaned from my mother, who despite a lifetime lived with him did not know details of his past; and from my sister, who was close to him.

My father’s mother died giving birth to his sister (or soon after), when my father was just two or three years old. He and his baby sister were then sent off to their maternal grandfather’s home. My Dad’s father was a Postmaster by profession: he probably could not have undertaken to care for two baby children. He never remarried. As for my father, growing up in his grandparents’ home seems to have left an indelible imprint on his life and values. It also left a deep affection and loyalty to ‘look after’ his baby sister throughout her life. It may be that he had an unhappy childhood in this stern and austere home, which may be the reason for his reluctance to talk about his childhood: we shall never know.

His maternal grandfather with whom he grew up was the Reverend Seth Christmas, an Anglican clergyman. He was so named because he was born on Christmas day, given the name ‘Christmas’, and living up to his name, died on Christmas day! Growing up in the austere Reverend’s home seems to have instilled in my father certain ‘Christian’ values, as taught by the missionaries at that time.

Apart from the usual Christian commandments, they branded smoking and drinking alcohol as ‘sins’. When my father was told that my elder brother (who was already a medical doctor by then) was smoking, he confidently declared: ‘None of my children will ever drink or smoke!’ This hope and certitude was unfortunately betrayed by all three of his sons, who all smoked and drank!

This treatment of drinking as a sin is also illustrated by another story. At the usual ‘rag’ on initiation when entering Medical College, the seniors made the freshmen suffer all sorts of indignities. One of them was to drink half a bottle of arrack in one go. My father, true to his ‘Christian’ principles, refused to touch liquor. Try as they may, he refused to drink. Ultimately in disgust, they banged the bottle of arrack on his head and poured the contents over his head! Undoubtedly, silent obstinacy was one of his traits!

My father had his early education at St. John’s College, Jaffna. He thereafter finished his high-school education at Royal College, Colombo, which was the best school in those days. Fortunately for us, he insisted that all his sons attend Royal College too. He thereafter entered Medical College, and after obtaining his medical degree, joined government service as a doctor. My mother, going through his few personal things after his death, found the Gold Medal for Surgery, which he had won in Medical College. He seems to have won this over Sir Nicholas Attygalle (his batch-mate) who later became one of the the most recognized surgeons in Sri Lanka. This characterizes my father’s modesty, since neither his wife nor his children knew of this achievement before.

My father was not an impressive man, either in physical appearance (he was never smartly dressed) or in career achievement; nor was he worldly-wise. He was undoubtedly very intelligent – as seen by his achievements in medical college. This intelligence ran in his mother’s family: but so also did a strain of depression. For instance, his mother’s brother, S.K Rutnam (the husband of Dr. Mary H. Rutnam), despite obtaining an M.A. degree from Princeton University (USA) as early as 1915, ended his life in depression. Depression also seems to have run in other lines of the family, originating from my father’s mother’s side of the family.

I can list only some of the posts my father held as a government doctor – due to my lack of knowledge. As a bachelor, he seems to have served in different posts around Kurunegala in the North-Western Province. I know that he served as a doctor in the Jaffna hospital in 1927, since I was born during his stint there. He seems thereafter to have switched to the field of public health, after which he was posted as the junior doctor in Mandapam Camp, where I spent the first five years of my life.

He was then selected for a government scholarship to England for post-graduate studies in public health. On his return to Ceylon, he served as Medical Officer of Health in the Batticaloa District (during World War II) for five years. Thereafter, he was appointed as Port Health Officer in charge of all health measures in the port of Colombo, which was the busiest port in Asia at that time. When he was passed over for appointment as Director of Health Services in charge of the whole Department of Health, he opted for a transfer as Medical Superintendent of Mandapam Camp where he would be his own boss. This was a quarantine station located in South India in the charge of Ceylon government doctors, whose aim was to prevent infectious diseases such as smallpox and cholera being brought to Ceylon from India, mainly by plantation workers destined for the tea estates of Ceylon. He served in charge of Mandapam Camp for eight-10 years, until his retirement.

In the latter capacity, he was in charge of about 7,000 people covering about 700 acres of land. We lived in a posh house with all the modern amenities, a garden of more than two acres of land, two full-time gardeners and a swimming pool. He was also the boss of about 50 uniformed security guards (needed to keep the detainees under enforced quarantine), dressed in Indian military-style khaki uniforms, replete with puttees and turbans. These guards would salute him whenever he passed, even if on the other side of the road, springing to attention and saluting him in mid-flight. To which my father, a modest and self-effacing man, would respond with an embarrassed, downcast eyes-salute!

He was socially awkward in company – which was more than compensated for by my mother, who thrived on conversation. He was not really into sports, although he played soccer in his youth and played a passable game of tennis in his ‘forties. In Mandapam Camp in his fifties, having walked about two miles in the sun to the railway station (to pass the passengers in the Ceylon-bound train), he would come back home and recline in his easy chair, saying that he was ‘fagged’ (tired).

I have some funny stories to relate about his life as a young government doctor. When posted in a wild part of the country in British colonial times, patients would come to his clinics from remote villages. Once, looking down at his records, he called for the next patient – and a cow walked in! When posted in another remote town, he was assigned a government bungalow adjoining thick jungle. My father loved to have chickens pecking around his yard and enjoyed feeding them; whereafter, the chickens would spend the rest of the day foraging in the jungle.

One day, my father’s big boss from Colombo was coming on ‘inspection’. My father invited him to lunch, hoping to give him chicken curry. But when he went to look for his chickens, they were all away, foraging in the jungle. In desperation, he got out his shotgun and went into the jungle to hunt his own chickens!

When I grew up, I was amazed at the number of relatives whom my father had been financially supporting. He seems to have undertaken the responsibility of helping his mother’s sisters and their children. This was despite not having really known his mother, who must have died when he was barely two years old. He seems to have financed a nephew through medical school, while providing monthly financial aid to his two maternal aunts and their children. My mother did not object, because she knew that he considered this to be his duty: she also knew that although quiet, he was still a very stubborn man!

My father seems to have valued financial security more than making more money. He neither saved nor invested – even in a home. He seems to have spent his entire salary in supporting his children and his mother’s sisters and their families. My mother relates this example of his not caring for money. The government in those days accepted that while government doctors should work in the hospital during office-hours, they could thereafter see patients privately at home for a fee.

My father would not charge a fee even when patients were seeking to see him privately. My mother reported cases where he was called urgently to poor patients’ homes but still would not take a fee, despite bearing the cost of transport himself. Other doctors in the area were naturally upset, since all the patients were flocking to my father. He saw it as his duty as a doctor to treat all patients who came to him. The other doctors came to him to object, arguing that he should charge a fee – because he was offering unfair competition!

To overcome this dilemma, my father started working in the hospital till night, so that patients could see him free of charge. Finally to avoid this predicament altogether, he moved into the field of public health, where the Government provided an extra allowance in lieu of private practice. Instead of becoming a surgeon, he chose to move into a less-paying field, which paid enough for his needs -which included looking after his mother’s sisters and their families! He was not ambitious for himself: he was merely putting personal duty, as he saw it, before self.

I too had experience of his ‘money is not important’ thinking. I had by this time got into the Ceylon Civil Service. At the age of 27 years (in 1954), I was approached to be interviewed for the post of Marketing Manager at Unilevers (Lever Bros). I was selected for the post (as a trainee) and offered a salary (as a trainee) more than six times of that which I was earning in the Ceylon Civil Service.

Since I was undecided, I wrote to my father for advice. I did not expect the thundering reply that I received from my usually quiet and indulgent father: “I did not think that any of my sons would stoop to filthy lucre like this!” I was stung to the quick by this response, because I too had been brought up in his way of thinking! So I shamefacedly turned down the post – though I had other reasons too.

I remember that my father never touched me, either in love or in anger, beyond my age eight years. I cannot remember him ever cuddling or hugging me, although I heard that he did this when I was little. He always maintained a distance when we were older, seeming shy of his own children! On the other hand, he never raised his hand against me, nor ever beat or scold me or my siblings. Nor did he ever ask me to study, nor make any attempt to supervise or check on my studies – though I know that he was very interested in my school results, which were undoubtedly conveyed to him by my mother.

It is only when I reached maturity that I realized that he ‘ruled’ us not only by example, but also by expectation. I don’t think that he was subtle and devious enough to realize this: but he achieved this result without even trying! He lived by very high standards of duty and integrity: he merely expected us to do the same. These expectations filtered down to us not directly from him, but from various uncles and aunts, bringing a feeling of guilt if we did not live up to his high standards and expectations. He was not an impressive man either by outward appearance or career achievement, but as I grew older, I grew to respect him more and more for the highly principled man that he was.

He was a remote and uncommunicative father, whom we often reached only through my mother. This is with the exception of my sister who was more familiar with him because she grew up mostly at home. He was, however, very considerate and indulgent towards his children. Each time that I was leaving for school after the holidays at home, he would sidle up to me and without looking me in the eye (he was embarrassed), would shyly slip a wad of pocket money into my hand, saying stiffly “pocket money” and hurry away.

When I looked at the money, it was always too much. When I ran behind him to protest, he would hasten away in embarrassment. I had to go to my mother to ‘complain’ that it was too much, and give her ‘the excess’ to return to my Dad. I found out later that my elder brother too had habitually been doing the same.

I have to relate another episode that shows his indulgence towards his children. Once when I was at home on holiday (I must have been about 16 years old at that time – and a confirmed athlete and rugby player), I came to the verandah where he was reclining on his ‘easy chair’ to chat with him. I found him struggling to get out of his ‘easy chair’ in order to offer it to me, although there were many other chairs around! I had to entreat him repeatedly to please sit down in his own chair, in his own house!

I conclude with the following personal story, as a tribute to my father. After my degree, I undertook a survey of the Veddas, involving a walk of 250 miles through jungles and drinking dirty water. I consequently developed severe dysentery – and hardly managed to walk the 100 miles through jungles to get back to my starting point. When I finally returned to my starting point, I found that the person with whom I had left all my money (since I had no use for money in the jungle) had gambled it all away!

I was thus left with absolutely no money at all and unable to return to Colombo for urgent hospitalization. Sick, weak, desperate and almost collapsing, I spent the last 15 cents I had on bus fare to reach a place closer to Colombo. (I was foolishly trying to go towards Colombo – although I knew that I could not reach it!) In that God-forsaken place I came across a government dispensary at the edge of the jungle (near Padiyatalawa).

Meanwhile, night had fallen – and the dispensary was closed. I was desperate now, with no money even to feed myself. When I shouted for urgent medical help, a window opened and a double-barrel gun poked out, since this was a jungle outpost where bandits were at large. I shouted explanations in English, in order to sound ‘educated’. (I looked a bandit myself, clad in my khaki kit, which I had worn for months in a row, my slouch khaki hat and a four month beard).

Afraid and annoyed, the Apothecary shouted roughly, asking my name and what I wanted. When I gave my name (‘Arulpragasam’ was a very uncommon name at that time), he asked whether I was, by any chance, a relative of Dr. Arulpragasam. When I said that I was his son, his attitude changed completely. He said: “Come in, my son” – although he was a Sinhalese gentleman, and I was not his son.

He went on to say: “Your father was the best boss that I have ever worked for, and the most decent gentleman that I have ever known”. He gave me some food, and after treating me for dysentery, he even lent me money for a third class railway ticket (which was all he could afford) back to Colombo. Whenever I think of this episode, tears come to my eyes: for I remember that it was the name of my father that saved me on this most desperate day of my life!

My father died of a brain aneurism in Jaffna at the age of 67 years. He passed away before any of his sons could reach him, although my sister was able to do so. My father’s remains are buried in the graveyard at St. John’s Church, where he had worshipped as a boy. When the ‘Eelam war’ was over, I had the grave rebuilt and a new headstone installed. When I look at these photos now, it is with sadness: sadness because we did not show the love and respect for him that he had for us. He taught us, at least posthumously, what true love, integrity and duty really meant.

P.S. My father had endowed a prize at St. John’s College, Jaffna, for English Oratory. This was in honour of his father, Mr. Cornelius Arulpragasam. Jega (my brother) and I have augmented this endowment, renaming the prize as “The Cornelius and Dr. Arulpragasam Prize for English Oratory”. This prize serves to remind me of my father – and of my origins.

Features

The heart-friendly health minister

by Dr Gotabhya Ranasinghe

Senior Consultant Cardiologist

National Hospital Sri Lanka

When we sought a meeting with Hon Dr. Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Health, he graciously cleared his busy schedule to accommodate us. Renowned for his attentive listening and deep understanding, Minister Pathirana is dedicated to advancing the health sector. His openness and transparency exemplify the qualities of an exemplary politician and minister.

Dr. Palitha Mahipala, the current Health Secretary, demonstrates both commendable enthusiasm and unwavering support. This combination of attributes makes him a highly compatible colleague for the esteemed Minister of Health.

Our discussion centered on a project that has been in the works for the past 30 years, one that no other minister had managed to advance.

Minister Pathirana, however, recognized the project’s significance and its potential to revolutionize care for heart patients.

The project involves the construction of a state-of-the-art facility at the premises of the National Hospital Colombo. The project’s location within the premises of the National Hospital underscores its importance and relevance to the healthcare infrastructure of the nation.

This facility will include a cardiology building and a tertiary care center, equipped with the latest technology to handle and treat all types of heart-related conditions and surgeries.

Securing funding was a major milestone for this initiative. Minister Pathirana successfully obtained approval for a $40 billion loan from the Asian Development Bank. With the funding in place, the foundation stone is scheduled to be laid in September this year, and construction will begin in January 2025.

This project guarantees a consistent and uninterrupted supply of stents and related medications for heart patients. As a result, patients will have timely access to essential medical supplies during their treatment and recovery. By securing these critical resources, the project aims to enhance patient outcomes, minimize treatment delays, and maintain the highest standards of cardiac care.

Upon its fruition, this monumental building will serve as a beacon of hope and healing, symbolizing the unwavering dedication to improving patient outcomes and fostering a healthier society.We anticipate a future marked by significant progress and positive outcomes in Sri Lanka’s cardiovascular treatment landscape within the foreseeable timeframe.

Features

A LOVING TRIBUTE TO JESUIT FR. ALOYSIUS PIERIS ON HIS 90th BIRTHDAY

by Fr. Emmanuel Fernando, OMI

Jesuit Fr. Aloysius Pieris (affectionately called Fr. Aloy) celebrated his 90th birthday on April 9, 2024 and I, as the editor of our Oblate Journal, THE MISSIONARY OBLATE had gone to press by that time. Immediately I decided to publish an article, appreciating the untiring selfless services he continues to offer for inter-Faith dialogue, the renewal of the Catholic Church, his concern for the poor and the suffering Sri Lankan masses and to me, the present writer.

It was in 1988, when I was appointed Director of the Oblate Scholastics at Ampitiya by the then Oblate Provincial Fr. Anselm Silva, that I came to know Fr. Aloy more closely. Knowing well his expertise in matters spiritual, theological, Indological and pastoral, and with the collaborative spirit of my companion-formators, our Oblate Scholastics were sent to Tulana, the Research and Encounter Centre, Kelaniya, of which he is the Founder-Director, for ‘exposure-programmes’ on matters spiritual, biblical, theological and pastoral. Some of these dimensions according to my view and that of my companion-formators, were not available at the National Seminary, Ampitiya.

Ever since that time, our Oblate formators/ accompaniers at the Oblate Scholasticate, Ampitiya , have continued to send our Oblate Scholastics to Tulana Centre for deepening their insights and convictions regarding matters needed to serve the people in today’s context. Fr. Aloy also had tried very enthusiastically with the Oblate team headed by Frs. Oswald Firth and Clement Waidyasekara to begin a Theologate, directed by the Religious Congregations in Sri Lanka, for the contextual formation/ accompaniment of their members. It should very well be a desired goal of the Leaders / Provincials of the Religious Congregations.

Besides being a formator/accompanier at the Oblate Scholasticate, I was entrusted also with the task of editing and publishing our Oblate journal, ‘The Missionary Oblate’. To maintain the quality of the journal I continue to depend on Fr. Aloy for his thought-provoking and stimulating articles on Biblical Spirituality, Biblical Theology and Ecclesiology. I am very grateful to him for his generous assistance. Of late, his writings on renewal of the Church, initiated by Pope St. John XX111 and continued by Pope Francis through the Synodal path, published in our Oblate journal, enable our readers to focus their attention also on the needed renewal in the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka. Fr. Aloy appreciated very much the Synodal path adopted by the Jesuit Pope Francis for the renewal of the Church, rooted very much on prayerful discernment. In my Religious and presbyteral life, Fr.Aloy continues to be my spiritual animator / guide and ongoing formator / acccompanier.

Fr. Aloysius Pieris, BA Hons (Lond), LPh (SHC, India), STL (PFT, Naples), PhD (SLU/VC), ThD (Tilburg), D.Ltt (KU), has been one of the eminent Asian theologians well recognized internationally and one who has lectured and held visiting chairs in many universities both in the West and in the East. Many members of Religious Congregations from Asian countries have benefited from his lectures and guidance in the East Asian Pastoral Institute (EAPI) in Manila, Philippines. He had been a Theologian consulted by the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences for many years. During his professorship at the Gregorian University in Rome, he was called to be a member of a special group of advisers on other religions consulted by Pope Paul VI.

Fr. Aloy is the author of more than 30 books and well over 500 Research Papers. Some of his books and articles have been translated and published in several countries. Among those books, one can find the following: 1) The Genesis of an Asian Theology of Liberation (An Autobiographical Excursus on the Art of Theologising in Asia, 2) An Asian Theology of Liberation, 3) Providential Timeliness of Vatican 11 (a long-overdue halt to a scandalous millennium, 4) Give Vatican 11 a chance, 5) Leadership in the Church, 6) Relishing our faith in working for justice (Themes for study and discussion), 7) A Message meant mainly, not exclusively for Jesuits (Background information necessary for helping Francis renew the Church), 8) Lent in Lanka (Reflections and Resolutions, 9) Love meets wisdom (A Christian Experience of Buddhism, 10) Fire and Water 11) God’s Reign for God’s poor, 12) Our Unhiddden Agenda (How we Jesuits work, pray and form our men). He is also the Editor of two journals, Vagdevi, Journal of Religious Reflection and Dialogue, New Series.

Fr. Aloy has a BA in Pali and Sanskrit from the University of London and a Ph.D in Buddhist Philosophy from the University of Sri Lankan, Vidyodaya Campus. On Nov. 23, 2019, he was awarded the prestigious honorary Doctorate of Literature (D.Litt) by the Chancellor of the University of Kelaniya, the Most Venerable Welamitiyawe Dharmakirthi Sri Kusala Dhamma Thera.

Fr. Aloy continues to be a promoter of Gospel values and virtues. Justice as a constitutive dimension of love and social concern for the downtrodden masses are very much noted in his life and work. He had very much appreciated the commitment of the late Fr. Joseph (Joe) Fernando, the National Director of the Social and Economic Centre (SEDEC) for the poor.

In Sri Lanka, a few religious Congregations – the Good Shepherd Sisters, the Christian Brothers, the Marist Brothers and the Oblates – have invited him to animate their members especially during their Provincial Congresses, Chapters and International Conferences. The mainline Christian Churches also have sought his advice and followed his seminars. I, for one, regret very much, that the Sri Lankan authorities of the Catholic Church –today’s Hierarchy—- have not sought Fr.

Aloy’s expertise for the renewal of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka and thus have not benefited from the immense store of wisdom and insight that he can offer to our local Church while the Sri Lankan bishops who governed the Catholic church in the immediate aftermath of the Second Vatican Council (Edmund Fernando OMI, Anthony de Saram, Leo Nanayakkara OSB, Frank Marcus Fernando, Paul Perera,) visited him and consulted him on many matters. Among the Tamil Bishops, Bishop Rayappu Joseph was keeping close contact with him and Bishop J. Deogupillai hosted him and his team visiting him after the horrible Black July massacre of Tamils.

Features

A fairy tale, success or debacle

Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement

By Gomi Senadhira

senadhiragomi@gmail.com

“You might tell fairy tales, but the progress of a country cannot be achieved through such narratives. A country cannot be developed by making false promises. The country moved backward because of the electoral promises made by political parties throughout time. We have witnessed that the ultimate result of this is the country becoming bankrupt. Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet.” – President Ranil Wickremesinghe, 2024 Budget speech

Any Sri Lankan would agree with the above words of President Wickremesinghe on the false promises our politicians and officials make and the fairy tales they narrate which bankrupted this country. So, to understand this, let’s look at one such fairy tale with lots of false promises; Ranil Wickremesinghe’s greatest achievement in the area of international trade and investment promotion during the Yahapalana period, Sri Lanka-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (SLSFTA).

It is appropriate and timely to do it now as Finance Minister Wickremesinghe has just presented to parliament a bill on the National Policy on Economic Transformation which includes the establishment of an Office for International Trade and the Sri Lanka Institute of Economics and International Trade.

Was SLSFTA a “Cleverly negotiated Free Trade Agreement” as stated by the (former) Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Malik Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate on the SLSFTA in July 2018, or a colossal blunder covered up with lies, false promises, and fairy tales? After SLSFTA was signed there were a number of fairy tales published on this agreement by the Ministry of Development Strategies and International, Institute of Policy Studies, and others.

However, for this article, I would like to limit my comments to the speech by Minister Samarawickrama during the Parliamentary Debate, and the two most important areas in the agreement which were covered up with lies, fairy tales, and false promises, namely: revenue loss for Sri Lanka and Investment from Singapore. On the other important area, “Waste products dumping” I do not want to comment here as I have written extensively on the issue.

1. The revenue loss

During the Parliamentary Debate in July 2018, Minister Samarawickrama stated “…. let me reiterate that this FTA with Singapore has been very cleverly negotiated by us…. The liberalisation programme under this FTA has been carefully designed to have the least impact on domestic industry and revenue collection. We have included all revenue sensitive items in the negative list of items which will not be subject to removal of tariff. Therefore, 97.8% revenue from Customs duty is protected. Our tariff liberalisation will take place over a period of 12-15 years! In fact, the revenue earned through tariffs on goods imported from Singapore last year was Rs. 35 billion.

The revenue loss for over the next 15 years due to the FTA is only Rs. 733 million– which when annualised, on average, is just Rs. 51 million. That is just 0.14% per year! So anyone who claims the Singapore FTA causes revenue loss to the Government cannot do basic arithmetic! Mr. Speaker, in conclusion, I call on my fellow members of this House – don’t mislead the public with baseless criticism that is not grounded in facts. Don’t look at petty politics and use these issues for your own political survival.”

I was surprised to read the minister’s speech because an article published in January 2018 in “The Straits Times“, based on information released by the Singaporean Negotiators stated, “…. With the FTA, tariff savings for Singapore exports are estimated to hit $10 million annually“.

As the annual tariff savings (that is the revenue loss for Sri Lanka) calculated by the Singaporean Negotiators, Singaporean $ 10 million (Sri Lankan rupees 1,200 million in 2018) was way above the rupees’ 733 million revenue loss for 15 years estimated by the Sri Lankan negotiators, it was clear to any observer that one of the parties to the agreement had not done the basic arithmetic!

Six years later, according to a report published by “The Morning” newspaper, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) on 7th May 2024, Mr Samarawickrama’s chief trade negotiator K.J. Weerasinghehad had admitted “…. that forecasted revenue loss for the Government of Sri Lanka through the Singapore FTA is Rs. 450 million in 2023 and Rs. 1.3 billion in 2024.”

If these numbers are correct, as tariff liberalisation under the SLSFTA has just started, we will pass Rs 2 billion very soon. Then, the question is how Sri Lanka’s trade negotiators made such a colossal blunder. Didn’t they do their basic arithmetic? If they didn’t know how to do basic arithmetic they should have at least done their basic readings. For example, the headline of the article published in The Straits Times in January 2018 was “Singapore, Sri Lanka sign FTA, annual savings of $10m expected”.

Anyway, as Sri Lanka’s chief negotiator reiterated at the COPF meeting that “…. since 99% of the tariffs in Singapore have zero rates of duty, Sri Lanka has agreed on 80% tariff liberalisation over a period of 15 years while expecting Singapore investments to address the imbalance in trade,” let’s turn towards investment.

Investment from Singapore

In July 2018, speaking during the Parliamentary Debate on the FTA this is what Minister Malik Samarawickrama stated on investment from Singapore, “Already, thanks to this FTA, in just the past two-and-a-half months since the agreement came into effect we have received a proposal from Singapore for investment amounting to $ 14.8 billion in an oil refinery for export of petroleum products. In addition, we have proposals for a steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million), sugar refinery ($ 200 million). This adds up to more than $ 16.05 billion in the pipeline on these projects alone.

And all of these projects will create thousands of more jobs for our people. In principle approval has already been granted by the BOI and the investors are awaiting the release of land the environmental approvals to commence the project.

I request the Opposition and those with vested interests to change their narrow-minded thinking and join us to develop our country. We must always look at what is best for the whole community, not just the few who may oppose. We owe it to our people to courageously take decisions that will change their lives for the better.”

According to the media report I quoted earlier, speaking at the Committee on Public Finance (COPF) Chief Negotiator Weerasinghe has admitted that Sri Lanka was not happy with overall Singapore investments that have come in the past few years in return for the trade liberalisation under the Singapore-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement. He has added that between 2021 and 2023 the total investment from Singapore had been around $162 million!

What happened to those projects worth $16 billion negotiated, thanks to the SLSFTA, in just the two-and-a-half months after the agreement came into effect and approved by the BOI? I do not know about the steel manufacturing plant for exports ($ 1 billion investment), flour milling plant ($ 50 million) and sugar refinery ($ 200 million).

However, story of the multibillion-dollar investment in the Petroleum Refinery unfolded in a manner that would qualify it as the best fairy tale with false promises presented by our politicians and the officials, prior to 2019 elections.

Though many Sri Lankans got to know, through the media which repeatedly highlighted a plethora of issues surrounding the project and the questionable credentials of the Singaporean investor, the construction work on the Mirrijiwela Oil Refinery along with the cement factory began on the24th of March 2019 with a bang and Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his ministers along with the foreign and local dignitaries laid the foundation stones.

That was few months before the 2019 Presidential elections. Inaugurating the construction work Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said the projects will create thousands of job opportunities in the area and surrounding districts.

The oil refinery, which was to be built over 200 acres of land, with the capacity to refine 200,000 barrels of crude oil per day, was to generate US$7 billion of exports and create 1,500 direct and 3,000 indirect jobs. The construction of the refinery was to be completed in 44 months. Four years later, in August 2023 the Cabinet of Ministers approved the proposal presented by President Ranil Wickremesinghe to cancel the agreement with the investors of the refinery as the project has not been implemented! Can they explain to the country how much money was wasted to produce that fairy tale?

It is obvious that the President, ministers, and officials had made huge blunders and had deliberately misled the public and the parliament on the revenue loss and potential investment from SLSFTA with fairy tales and false promises.

As the president himself said, a country cannot be developed by making false promises or with fairy tales and these false promises and fairy tales had bankrupted the country. “Unfortunately, many segments of the population have not come to realize this yet”.

(The writer, a specialist and an activist on trade and development issues . )