Midweek Review

Modern view of the Island’s ancient past

Ruminations – II

By Seneka Abeyratne

The Sinhalese refer to themselves as ‘Indo-Aryans’ and to the Tamils as ‘Dravidians’. Implied in this distinction is the notion, conditioned by the ideas of the chauvinists and populists, that ‘Aryan’ blood is somehow superior to ‘Dravidian’ blood. Most historians now agree that the terms ‘Indo-Aryan’ and ‘Dravidian’ refer to a family of ancient languages originating in North India and South India, respectively, and that they have nothing to do with race or its physical attributes, such as complexion, height, build and facial features. Indeed, in terms of physical appearance, it is often difficult to distinguish between a Sinhalese, a Tamil and a South Indian.

When it comes to facial features and complexion, there is as much variety among the Sinhalese as among the Tamils, suggesting that both groups are ethnically far more diverse than is commonly assumed. The same is probably true of the smaller ethnic groups, such as Moslems and Burghers. The traditional view of supposed racial and cultural uniqueness, based on facile one-dimensional theories of migration and pure descent, is no longer considered valid.

It is not implausible to argue that over time the Tamil community, which is mainly of South-Indian origin, absorbed ethnic groups from other parts of India who shared certain cultural affinities with the Tamils, such as religion, caste, food habits, and traditional customs and practices. This may explain why some Ceylon Tamils look more like northern, western or eastern Indians than southern Indians.

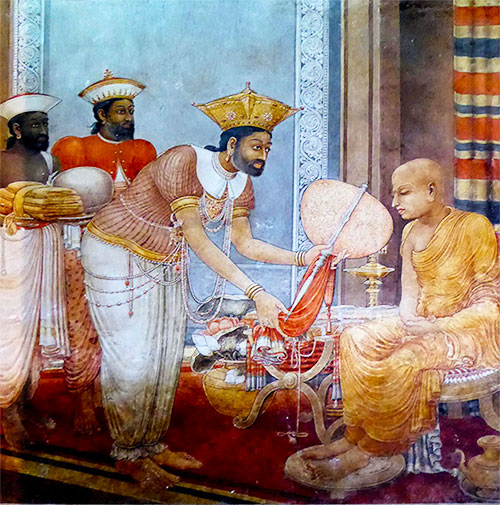

The Sinhalese likewise are ethnically diverse. While it may be true that the early settlers came from northwestern or northeastern India, later settlers likely came from other parts of India, including southern India. It is also possible that some synthesis occurred between early settlers and indigenous elements. Since it was common practice for ancient Sinhala kings and noblemen to marry into South Indian dynasties, we could assume that Sri Lanka and South India had close cultural and political ties from a very early age.

Even Vijaya, the purported founder of the Sinhala race, is believed to have married a princess from Madurai. Many of the Sinhala-speaking people in the Vanni region, north of Anuradhapura, are probably descendants of the Vanniyars, who are reputed to have migrated to the island from southern India. The periods 1056-1236 and 1473-1815 correspond to the Polonnaruwa and Kandyan kingdoms, respectively. During the former, there was a significant infusion of Pandyan blood into Sinhala royalty and during the latter, a similar infusion from Madurai.

The last line of kings to rule Kandy was the Tamil-speaking Madurai Nayaks, a Telugu dynasty. Given that Madurai is situated in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, it is difficult to imagine there was no commingling of Sinhalese and Tamil blood during this time. The Cheras, who came during the Portuguese period, injected a large dose of South-Indian blood into the southern littoral of Sri Lanka. The ethnic links between the Sinhalese and the South Indians are probably far more extensive than is commonly assumed.

Though the subcontinent figures prominently in Sri Lanka’s ethnic equation as per the periodic influx of settlers to the island from various parts of India during the Late Protohistoric to Early Historic Period (600 BCE-300 CE), we should not ignore the fact that the Sri Lankan gene is extremely diverse. There is evidence to suggest that in ancient times, people from Malaya and Indonesia migrated as far as Madagascar and the East African coast. It is therefore plausible to argue that while crossing the Indian Ocean, some of the boats carrying these people would have landed on our shores. Similar migrations would have occurred even in historic times. One has only to note the distinct Malay-Indonesian features of many a Sri Lankan to realise there must have been a continual migration of Southeast Asians to the island during historic and prehistoric times.

Melting Pot

A keen observer strolling through Kandy town, having noticed that some Kandyans resemble Malays or Javanese while others resemble Thais or Burmese, may arrive at the conclusion that Sri Lanka is and has always been a melting pot of different cultures. Some Kandyans also resemble the Burghers in respect of complexion and features. Hence one wonders how much ‘white’ blood seeped into the Sri Lankan gene pool during the four and a half centuries of western colonial rule.

It is a curious phenomenon that, despite its proximity to India, the island has more in common with Southeast Asia than with India in respect of climate and vegetation, as well as certain cultural practices. Duriyan, rambutan and mangosteens are found in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka but not elsewhere in South Asia. The food habits of Sri Lanka also demonstrate a strong Southeast Asian influence. Sri Lankans cook curries in coconut milk like the Malays and Indonesians and use lemongrass for flavouring certain dishes, as do the Thais. There is also a similarity in the peasant dress of Sri Lanka, Indonesia and Malaysia, especially in respect of females. The Malayo-Polynesian outrigger fishing boat (catamaran) is found in Sri Lanka but nowhere else in South Asia.

The only country practising Theravada Buddhism in South Asia is Sri Lanka but in Southeast Asia, there are many, such as Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos. The Buddhist factor figures prominently in the strong cultural and diplomatic ties that have existed between Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia for centuries.

From 1581 to 1591, Kandy was ruled by the Sitawaka king, Rajasinha I, who had converted to Hinduism. During this period Buddhism almost perished in the Kandyan kingdom due to the machinations of the Buddhist-turned-Hindu monarch. From 1591 to 1604 Kandy was ruled by Vimaladharmasuriya I, also known as Konappu Bandara, who succeeded in ousting Rajasinha I and reviving Buddhism with the assistance of ordained Burmese monks.

For the next hundred years or so, the Kandyan monarchs continued to protect and foster the religion. After the reign of Vimaladharmasuriya II ended (1687 to 1707), Buddhism again went into serious decline but was revived by Kirti Sri Rajasinha, who ruled from 1747 to 1782. This time it was a Thai monk named Upali Thera who came to the rescue. The Theravada monastic order known as Siam Nikaya was founded by him in Kandy in 1753 with the full support of the king. The other two main Theravada monastic orders in the island are the Ramanna Nikaya (Payagala) and the Amarapura Nikaya (Balapitiya). Both were founded by Sri Lankan bhikkhus who had been ordained in Myanmar.