Midweek Review

Current Crisis of Performing Arts Education in Sri Lankan Universities

E-learning and technocracy:

By Dr Saumya Liyanage

Introduction

During the first wave of corona outbreak, a group of academics gathered via Zoom online forum, at the invitation of Sripalee campus online radio, to discuss the challenges and opportunities in using online educational tools. Nearly 20 academics representing various universities in the country and other educational institutions took part in the discussion, which lasted for more than three hours. Its focus was mainly on how e-learning could be a solution to the challenge of social isolation and how to use zoom and other online tools to educate undergraduates.

From early months of 2020 till today, universities, schools, and other educational institutions have been affected by sudden closures and openings. As for university education, it is observed that gradual continuation of teaching, learning and assessments are continually disrupted. With the first wave of the COVID-19, university authorities introduced online teaching and learning activities to undergraduates, and online lectures were conducted accordingly. However, the situation today is becoming more intense. Subjects such as performing arts have been facing a myriad of difficulties in delivering lectures to students who are not physically present in universities. The advent of technology and online learning has given rise to some myths governing and overpowering the existing educational approaches and methods. This paper intends to discuss these myths.

Virtual Reality

For the last ten-fifteen years, the World Bank and the Ministry of Higher Education have spent millions of rupees on effecting changes to undergraduate education in the country. Therefore, it is not the COVID-19 that led to the germination of the idea of online and blended learning in universities. These technologies, especially LMS [Learning Management System], had been introduced to universities before COVID-19 and academics had various concerns and doubts about using them. LMS and other online projects had been in abeyance for years in the university sector while majority of learning and teaching took place with the help of onsite, teacher-centered education model.

The ideas of using online tools especially zoom conferencing and LMS, Google Classroom or Microsoft Team seem to be very fashionable to some of the academics who are hypnotically attached to World Wide Web and other such technologies. Some people are even fascinated by how students are using WhatsApp to share their lecture notes. My question is what is so new about using WhatsApp and sharing lecture notes if they repeat the same traditional teacher centered learning system with the help of a new technology. Of what use is new technology if students remain dependent on teacher centric learning method?

But there are ample resources and research already being conducted on how teaching performing arts could be carried out amidst a pandemic crisis and the pedagogical and philosophical challenges it faces (Asunka, 2008; Corbera et al., 2020; Demuyakor, 2020; González-Zamar and Abad-Segura, 2020; Rapanta et al., 2020; Sasere and Makhasane, 2020). But have we thought about establishing effective means of delivering performing arts education via e-learning modes in this country? Who does the research on how students get access to online facilities, and how they get access to available infrastructure? What are the methodological, philosophical, and practical issues that academics experience when teaching subjects such as performing arts? What solutions or remedies could be proposed to resolve these issues? What lessons we could learn from their counterparts facing such challenges? Universities, ministries, authorities remain mum.

Online and Onsite

As an effective teaching method, a learning mode like LMS could be a useful tool in engaging with students. However, it should be noted that no one can assure that these tools are the only way to deliver diverse undergraduate programmes that are being offered in the Sri Lankan universities. For instance, University of the Visual and Performing Arts offers degrees related to music, dance, drama, film studies, and visual arts. There are ways in which these online tools could be effectively used to deliver subject contents. But that does not justify the fact that these online tools are the sole means of delivering all courses and modules. There are significant limitations and incapability when it comes to teaching visual and performing art via online modes.

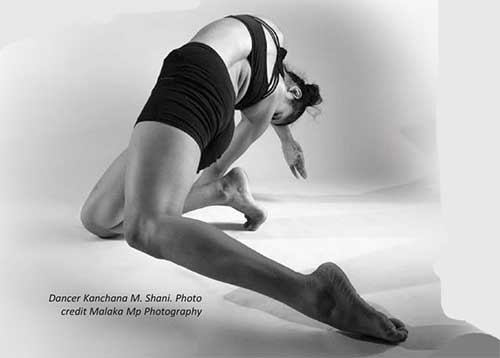

There is an epistemological question pertaining to knowledge generation as regards performing arts if the teacher-disciple engagement is disrupted in the classroom/studio/performance laboratory setting. As researchers argue that ‘[…] other forms of research are led by probably theory, plausible theory, and possible theory, a/r/tography is led by theorizing potential as it moves beyond the boundaries (O’Sullivan, 2001) of theory. A living practice is not about discovering knowledge but rather about “the feel of new forms of vitality” (Triggs et el., 2014, p. 256). Artists embrace the living of practice and becoming part of the variations within potential’s variations’ (Leavy, 2019, p. 37). Thus, arts education is not merely delivering theories to students but it contains arts making, learning, and knowing as interconnected ‘within the moment of art and pedagogical practices’ (ibid, p. 37).

Topics related to the value of liberal arts and humanities have been widely discussed in Sri Lankan academia (kathika, 2012, kathika, 2019). Arts based education/research generates key important skills and somatic knowledge that their impact upon a continual growth of a society is paramount. With a limited access created by online learning, those broader learning objectives, and graduate learning outcomes cannot be fulfilled. For instance, Arts-based education/research and particularly learning performing arts encourage diverse skills and knowledge spectrum within its corporeal engagement of learning.

In a studio/theatre/dance laboratory setting, teachers and students experience various haptic and other corporeal knowing. For instance, they discover new insights, explore novel learning methods, resolve problems, forge micro-macro connections, expose to holistic approaches, raise awareness and critical thinking, develop corporeal sensitivities, cultivate bodily receptive, raise ethical and moral awareness, challenge dominant ideologies, propose alternative perspectives, entertain multiple meanings, confront with prejudices, bring marginalized bodies to the forefront, increase emotional intelligence (Leavy 2019, pp. 8-11). I am literally speechless when I think of how to achieve these learning outcomes via e-learning. The fundamental point in arts based learning/research is that it is centralised with the human body. Artistic practice, creative outcomes, and empathic skills purely depend on the corporeality and action because, learning takes place when bodies move in space. Humans as Maxine Sheets-Johnston argues are animated beings and their motility is the key to learn (Sheets-Johnstone, 2009, 2011, 2013). But the question might be how then the e-learning would facilitate such corporeal and tangible environment virtually where students are fragmented and scattered in every corner of the country?

As seen above, if we need to teach performing arts online, we need to prepare subject contents designed to deliver online teaching. This work takes a lot of labor, infrastructure, and intellectual energy. It also consumes a considerable amount of time for academics to prepare their teaching materials and contents to be using online platforms. The question is whether university academics are ready, or being trained to do so. In some faculties, some academics still do not use emails to communicate with their peers. Therefore, with these constrains and limitations, I have a doubt whether sophisticated online learning platforms can be implemented overnight to deliver subject contents for students.

Escapism and Homogeneity

The establishment of e-learning mechanism in the universities popularises the idea that the teacher can avoid unnecessary engagements with student groups. The interaction between the lecturer and the group of students is on the wane due to many technological deficits experienced during the lecture. When the lecture is delivered, all the listeners should mute their mics and cameras. The result is the gradual declining of engagement between students and academics. This kind of arrangement helps teachers finish their assigned jobs without having to field questions.

The need for e-learning and its vital engagement in higher education were geared by the UGC and this suggestion resulted from the assumption that the university community, especially student body, is ‘still healthy and not affected by the pandemic’. There is a widely accepted assumption that student bodies are understood as a homogeneous entity where individual capabilities, health, and their social, cultural, and economic capacities are intentionally ignored. With the current COVID-19 situation, universities have ignored students who have poor economic backgrounds and cannot afford internet and Wi-Fi facilities to connect with university online teaching. What the authorities want is to show that universities are functioning well despite pandemic-related restrictions.

Technocracy and Domination

Another myth is that e-learning is an effective solution to the problem of disruptions to education. In the university sector, many course contents from medicine to performing arts have had to be delivered through online means. This virtual reality creates a false conception and ideological emphasis that without this kind of technological advancement, education will be doomed.

However, the university system seems to have ignored that the classical ways of teaching and learning are already being shattered and altered with the advent of new technology. Some of the disciplines in social sciences and humanities and also in performing arts and research are continually being threatened and marginalised by virtual learning approaches. The vital connection between students and teachers and the embodied relationship between them in shared learning environments are also being ignored. Finally, what the academic community is apparently unaware of in this technological advancement is that they are being subjugated to a social system and the technocracy that are beginning to govern the education system of this country. Disciplines that cannot adapt to e-learning methodologies are bound to be extinct sooner or later.

Conclusion

University education has been affected by the current corona outbreak. Previous traditional classroom learning activities and interactive sessions have given way to online teaching and learning. However, within Sri Lankan university, delivering subject contents to students’ bodies and engaging with them effectively remain an unresolved question. Among other disciplines, performing arts and some related disciplines have been affected by online teaching and academics and students both have experienced complex difficulties in delivering practical components and training via virtual modes.

However, it is alarming that with the intervention of online teaching and using distance learning apparatuses, technocracy has come to stay in the university system. This technocratic order emphasizes the need for the transformation and establishes online regulations ignoring some of subject specific requirements and natures of embodied learning. Fine arts and performing arts education is particularly at stake due to the new normal, and it is uncertain that how the universities or academic community would face these challenges in the future.

Reference list

Asunka, S. (2008). Online Learning in Higher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Ghanaian University students’ experiences and perceptions. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 9(3).

Corbera, E., Anguelovski, I., Honey-Rosés, J. and Ruiz-Mallén, I. (2020). Academia in the Time of COVID-19: Towards an Ethics of Care. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), pp.191–199.

Demuyakor, J. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Online Learning in Higher Institutions of Education: A Survey of the Perceptions of Ghanaian International Students in China. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 10(3), p.e202018.

González-Zamar, M.-D. and Abad-Segura, E. (2020). Implications of Virtual Reality in Arts Education: Research Analysis in the Context of Higher Education. Education Sciences, 10(9), p.225.

kathika (2012). The Role of Education in Taking Care of the World : The Value of the Liberal Arts and Humanities. [online] “කතිකා” සංවාද මණ්ඩපය. Available at: https://kathika.lk/2012/08/11/the-role-of-education-in-taking-care-of-the-world-the-value-of-the-liberal-arts-and-humanities/ [Accessed 11 Nov. 2020].

kathika (2019). Social Science and Humanities Education in the Universities in Sri Lanka and its Discontents: Some Reflections – Kumudu Kusum Kumara. [online] “කතිකා” සංවාද මණ්ඩපය. Available at: https://kathika.lk/2019/07/10/social-science-and-humanities-education-in-the-universities-in-sri-lanka-and-its-discontents-some-reflections/ [Accessed 11 Nov. 2020].

Leavy, P. (2019). Handbook of arts-based research. New York: The Guilford Press.

O’Neill, M.E. (2001). Corporeal Experience: A Haptic Way of Knowing. Journal of Architectural Education, 55(1), pp.3–12.

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L. and Koole, M. (2020). Online University Teaching During and After the Covid-19 Crisis: Refocusing Teacher Presence and Learning Activity. Postdigital Science and Education.

Sasere, O.B. and Makhasane, S.D. (2020). Global Perceptions of Faculties on Virtual Programme Delivery and Assessment in Higher Education Institutions During the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(5), p.181.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2009). Body and Movement: Basic Dynamic Principles. Handbook of Phenomenology and Cognitive Science, pp.217–234.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2011). From movement to dance. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 11(1), pp.39–57.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2013). Movement as a Way of Knowing. Scholarpedia, 8(6), p.30375.