Features

Contradictions in Trinco oil tank deal

By Neville Ladduwahetty

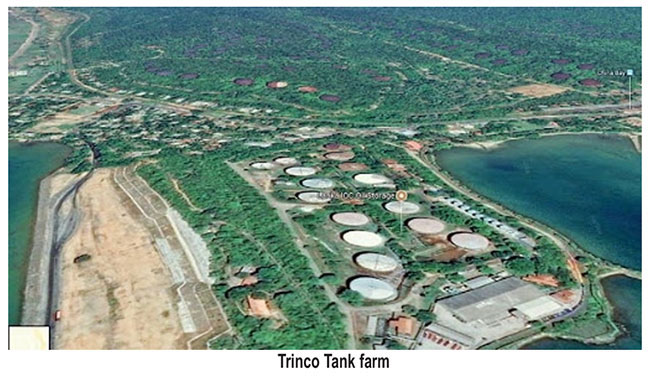

According to media reports the government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) has signed three new Agreements, dated 6 January, 2022 relating to the Trinco oil Tank Farms. The first with the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC), the second with the Lanka IOC PLC (LIOC), and the third with a Joint Venture Company incorporating the CPC holding 51% and LIOC holding 49% called Trinco Petroleum Terminal (Pvt.) Ltd. The three Agreements relate to the ninety-nine (99) Oil Tanks built during WWII on the basis of State leases, for a period of fifty (50) years. The first relates to twenty-four (24) tanks, the second to fourteen (14) tanks and the third to sixty-one (61) tanks.

As stated by the Minister of Energy Udaya Gammanpila, this current agreement is an outcome of the three previous agreements. In the course of an interview, he stated that the first was when “President J. R. Jayewardene agreed with India to develop and operate this tank farm jointly with India, so we have a bilateral obligation with India to develop jointly”. The second was when “Prime Minister Ranil Wickramasinghe, on 7 February 2003, leased out these tanks to India for 35 years. That is how they came into possession of these tanks. The third was when “Malik Samarawickrama – Sushma Swaraj MoU agreed with India to lease out the entire tank farm of 99 tanks to LIOC for a period of 99 years” (The Sunday Morning, January 16, 2022).

Minister Gammanpila has also said, “Sri Lanka was under obligation to India in respect of this tank farm through these three agreements. I had to negotiate with India in this backdrop. If I could ignore these agreements, I would have taken the entire tank farm into Sri Lanka’s possession; I would love to do that. Unfortunately, there are three agreements signed by previous governments and I am bound by them” (Ibid).

To claim that Sri Lanka is obligated by all three previous agreements is not only to assign equal status to all but also to accept the contradictions in the terms among the three agreements. For instance, the first agreement between Sri Lanka’s Head of State and the Prime Minister of India has no time bar while the second is by a Prime Minister of Sri Lanka to lease the tanks to India for a specified period of 35 years and the third, an agreement to lease all the tanks for 99 years, not to India but to a State entity of the government of India, LIOC. Furthermore, the first agreement was to develop the tanks jointly while the other two are on the basis of leasing them. Perhaps, India did not make an issue of violating the terms of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord because the subsequent agreements are more favourable to it.

The specifics of the latter two agreement are not available to the public. Even if their contents are available to the Minister and he was aware of the circumstances that caused a lease for 35 years with the State of India to be extended for 99 years to an entity of that State as being of equal standing as the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, this is not a tenable proposition. Furthermore, the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord is not limited to the oil tanks, whereas the other two agreements specifically relate only to the tanks. Therefore, as far as the tanks are concerned, there is every justification to address issues relating to them from a totally fresh perspective.

Minister Gammanpila claims this deal was a major achievement. The reason for such a claim is that until the agreements of January 6 2022 were signed, all 99 tanks had been leased either for 35 years or 99 years depending on which agreement one considers to be valid. Therefore, the agreement of January 6 2022 is a considered a gain because it regained 85 tanks that were in the possession of LIOC. Furthermore, the fact that 24 of the 85 would be exclusively operated by Sri Lanka and 61 jointly means a decided improvement. However, it must be clearly understood that the so called “gain” is only in respect of the tanks taken in isolation and not as part of a viable asset.

Could Sri Lanka have done even better and taken over all 99 tanks to be developed by Sri Lanka, while leaving the 14 tanks currently operated by LIOC for the remainder of the 35-year lease period as a measure of good faith? Since the provision of the Indo-Sri Lanka was for operating the entire Tank Farm jointly, and the agreements of 2003 and 2017 violated this provision, a claim could be made that sufficient grounds existed to take possession of all 99 tanks; a wish the Minister himself entertained during his interview.

REVISITING the AGREEMENT and its TERMS

How best to exploit the potential of these tanks has been the topic of much discussion and debate. However, the majority of these discussions have focused on these tanks as a legacy of World War II and how best to exploit its potential. It cannot be denied that taken in isolation, these tanks are nothing but 99 rusting steel tanks without much utilitarian value.

It is only in the context of its location that these tanks take on a whole new dimension and come alive as a vital economic asset because of its proximity to one of the best natural harbours in the world – the Trinco Harbour. Therefore, it is the Trinco Harbour that make these tanks a valuable asset.

These tanks were sited at this particular location because of the Trinco Harbour. Therefore, the tanks cannot be considered in isolation and independent of the Trinco Harbour. The tanks and harbour are inextricably linked and therefore it is absolutely vital that the tanks and the harbor are considered and treated as a single asset and not as separate assets. On such a basis, for the LIOC to hold 49% stake in the joint venture should be unacceptable because it amounts to the harbor being a give-away – a free gift to which a value cannot be assigned. Furthermore, the fact that the tanks amount to nothing but 99 steel containers without the harbour, strong grounds exist for Sri Lanka to revisit the deal and take possession of the tanks because the asset that transforms the tanks into an economically viable asset is the Trico Harbor, which is not associated with the deal.

Having taken possession of the tanks, Sri Lanka should perhaps restore a few tanks per year by seeking funds through local banks and pay back the loans by renting them to interested parties such as the LIOC and others who may find it profitable to store petroleum products when prices are low. Such an approach would be in keeping with the current government’s policy of self-reliance. Furthermore, the pace of restoration could be undertaken to keep in pace with the demand from interested parties.

CONCLUSION

The current agreement signed on 06 January 2022, which entitles Sri Lanka to operate 24 tanks exclusively and 61 tanks as a joint venture with India is decidedly an achievement over the agreements of 2003 and 2017, which leased these tanks for 35 and 99 years, respectively. However, the implication of these agreements is that both India and Sri Lanka have agreed that deviating from the basis of developing the tanks jointly as stated in the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord is acceptable.

All these agreements relate to the 99 tanks that by themselves amount to nothing but steel storage containers without much utility value. However, they have the potential to be transformed into a vital economic asset because of their proximity to one of the best natural harbours in the world – the Trinco Harbour. Therefore, any agreement relating to the tanks should take into account the fact that without the Trinco Harbour the tanks by themselves have little value. Consequently, the tanks and the Trinco harbour should be treated as a single asset and not as separate and unrelated assets. Under the circumstances, a share distribution of 51/49 favours India disproportionately because the asset that makes the enterprise a viable venture, namely the Trinco Harbour, belongs to Sri Lanka. It is this aspect that makes the 06 January2022 agreement unacceptable because the asset value of the Trinco Harbour has been totally disregarded.

Coupling such a context with the policy to deviate from the concept of jointly developing the tanks into one of leasing in the agreements of 2003 and 2017 gives Sri Lanka the opportunity to renegotiate and take possession of all 99 tanks, but permits LIOC to continue operating the 14 tanks until the current lease period lapses. Having renegotiated a fresh deal, Sri Lanka should restore a few tanks at a time with finances from local Banks, and pay back the loans by renting them to interested customers to store petroleum products.

Such a strategy would be in keeping with the spirit of self-reliance that has been with the Peoples of Sri Lanka and manifests itself occasionally, the most recent being the demand for Sri Lanka to construct the East Container Terminal that the Government intended to outsource. The spirit of self-reliance is not dead. Its resurgence awaits leadership. It is in such a spirit that the Trinco Tank Farm deal should be revisited.