Features

Conservation – a rational basis and early visits to Yala

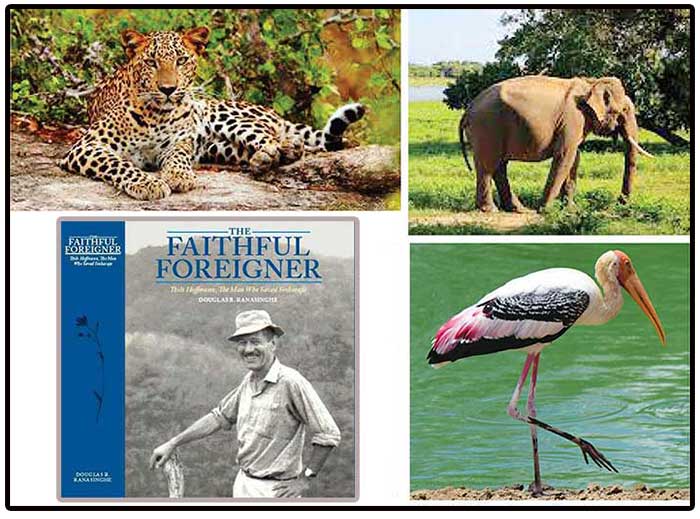

Excerpted from the authorized biography of Thilo Hoffmann

by Douglas. B. Ranasinghe

Over the decades Thilo Hoffmann has been persistent not only in labouring to protect the environment, flora and fauna of Sri Lanka, but also, in writings and speeches, persuading others to do so, and explaining the rationale for doing so.

A good general summary of the reasons to conserve nature is seen in an article by him published in Loris, adapted from his address as President of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society (WNPS) at its Annual General Meeting held December 1972. Titled The Need for a Policy’, it is reproduced here as Appendix I. He stated:

“Politicians and administrators alike regard wildlife and conservation even in this day and age as matters of little consequence, and those who care for the environment in Sri Lanka are belittled as ‘enthusiasts’, more or less harmless cranks who need not be taken seriously. Yet the conservation of the country’s natural resources has already become a major national issue, and for the good of the people, the most serious notice should be taken of the present situation and of our duty to conserve at least what is left of some important natural resources and to rebuild the lost ones.

“One most pertinent question has been neither posed nor answered. What will happen to our national parks and reserves in the years to come when the population will double again in less than a quarter of a century, when within one generation there will not be twelve but twenty-five million people in this island? Will there be room for national parks and sanctuaries, or for animals, as some would put it. The unthinking will have a quick and ready answer, and that answer is a plain: “No, there will be no room for wild animals. We must look after the needs of the people. The people must come first.” Such answers only serve to display a lack of appreciation of the issues involved and the absence of vision of those who hold these views.”

He stressed that the opposite is true, that National Parks and other protected areas are basic necessities for the people, which grow in importance as the population increases and as the country and the land become developed.

“We must decide and define,” he contended, “why wildlife and nature reserves, forest reserves, scenic and landscape reserves, catchment areas and water reserves, coastal and marine reserves are needed. He listed these purposes in order of importance for Sri Lanka:

“1. Recreational. Human well-being. People need to re-charge the system when run down from stresses and strains. There is aesthetic appreciation of free nature; there is enjoyment, healthy pleasure.

2. Scientific. All National Parks are of scientific value present and future, also especially Sinharaja, Ritigala, Hakgala, and a number of ecosystems which were then not protected, such as coastal swamps, wetlands, marine habitats, hilltops in the low-country and mountain forests.

3. Cultural. Free nature, plants, flowers, animals, reptiles and insects, the land, the water and the air have from time immemorial played an important role in the arts, the philosophy, the sciences and religions of people all over the world, and perhaps particularly so in Sri Lanka. We cannot lose or sacrifice these Sri Lankan cultural values.

4. Productive. Some of the reserves mentioned – such as forests, coral reefs and mangroves – are directly and economically productive but only so long as they are protected, cared for and kept in a natural state. They are also indirectly productive through their influence on human well-being and the human environment.”

At Yala

Thilo Hoffmann remembers well his earliest jungle visit. It was to the Yala East Intermediate Zone, in 1947, when it was a favourite place for ‘sportsmen’. Controlled hunting with permits was allowed, he was young, he was not a member of the Wildlife Society and he joined a small group of Ceylonese friends.

The conservation areas in modern Ceylon were instituted at the beginning of the 20th century. Then there were three Sanctuaries, namely Wilpattu, Wasgomuwa and Yala, and a Resident Sportsmen’s Reserve, the present Ruhunu National Park Block I. Outside these the killing of wild animals for gain or sport was freely allowed.

In 1938 the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance created Strict Natural Reserves, National Parks and Intermediate Zones. The last mostly bordered Parks and served as buffers. Shooting was allowed anywhere else of animals harmful to agriculture, such as wild boar, and within these Zones also certain others on permit.

During the second such visit an unusual incident left a lasting impression on Thilo. It is appropriate that, as a result, he would be the person most responsible for the incorporation of Intermediate Zones into the National Parks by the Wildlife Department, for removing the claim which supported hunting in the constitution of the Wildlife Society, and later for the initiation of the so-called ban on shooting (its prohibition by the State).

Thilo has always felt compassion for all living things, including plants. He went on the two trips in a spirit of adventure and exploration. Hunting was then not only legal but a widespread recreation. Yet, he shot very few animals and prevented others from being hit. He describes the visit and experience:

“In those days Baurs, like other European firms in Sri Lanka, expected its expatriate employees to spend the annual leave of two weeks up country so as to make them available again for work in a fit state. However, all my leisure hours and holidays and weekends were spent in the low-country jungles.

“My earliest real stay in the jungle was during the drought of 1947, when I went to Okanda with my Swiss colleague Hans Sigg and three Ceylonese friends of similar age, Ben Hamer, Anton Soertz and Douggie de Zilwa. We spent two weeks there, with the single-roomed Forest Department circuit hut as our headquarters. A tracker and a cook were recruited at Panama.

“The Game Ranger at Okanda was Mr Overlunde, a very large and very friendly Burgher, who lived in this remote place with his wife and baby daughter. I remember him most vividly by the mountains of rice and curry he used to heap on his plate at the Arugam Bay resthouse when we went there for provisions.

“Our party shot a leopard and other animals, with permits, including hare and jungle-fowl for the pot. One day, armed with rifles three of us were sitting on the bund of a dry tank in the Bagura area. It was really a bad drought, with not a drop of water for miles around. Three wild boars came trotting towards us. We decided that each of us take one. We counted one, two, three, and three shots went off more or less together.

“Only one boar was hit. It fell and was screaming. The other two ran off instinctively. Then they came back to their fallen companion and tried to raise the wounded animal on its legs. But its spine was broken above the shoulder. The return despite the danger was like a very human reaction. Because of it the two also met with their deaths. It made an impression on me and from then on I never shot another animal. (To attribute human actions to animals is called anthropomorphism, a common intellectual failing.)

“The dead leopard taught me a jungle lesson. It had been shot around midnight at a rock water hole deep inside the forest. At dawn, when we were preparing to return to camp, I patted it on the head, as I would a dog. I paid for this gesture of sympathy. Some time later my right arm and shoulder were teeming with ticks, which had been leaving the dead body. The most painful experience with these tiny insects is when you walk into a ‘nest’ of larvae on a twig. Hundreds of these parasites the size of a grain of sand then bore into your skin, causing painful swelling and lasting irritation.

“We may note here that bears make poor trophies because the fur is shaggy, but males were and are sometimes shot for their well-developed penis bone!

“The following year again we spent our annual holidays at Okanda, this time accompanied by Mae. One night after the breakdown of our car we walked from Panama to Okanda, a distance of over 12 km, then mostly jungle. We arrived as dawn was breaking.”

It needs to be mentioned here that up to 1950 the Department of Wildlife, created in 1938 under the new Ordinance, was a part of the Forest Department and administered by it. The Conservator of Forests, then Mr J. A. de Silva, was also Acting Warden of the Department of Wildlife.

Only in 1950 were financial provisions made for a separate Department of Wildlife. Some Forest staff were then transferred to it: an Assistant Warden, 10 Forest Guards and 33 Forest Watchers. Newly, 30 Game Rangers were recruited, followed in 1951 by another 30 Game Guards and 57 Game Watchers, most of them from the vicinity of the Reserves. Mr C. W. Nicholas was appointed the first Warden of the independent Department.

It may be added that in those early years there were only two bungalows in the entire Yala complex of Reserves. The old Yala bungalow stood under large trees high over a bend in the Menik Ganga, and was a delightful place. It had been built at the beginning of the 20th century by H. E. Engelbrecht, the Boer ex-prisoner of war, after he was appointed the first guardian of the Yala Resident Sportsmen’s Reserve.

This was unceremoniously demolished when the present two-storey monstrosity was built to replace it. Remnants of the foundation can still be seen. Although the river was eating into the bank at that time, the old building was never in acute danger. The other bungalow was at Buttawa.

In other ways, too, Yala has changed greatly. Over-provision of visitor facilities and over-visitation by local and foreign tourists has by now greatly damaged the character of Yala as a prime nature conservation area. Even in the materialistic West it has now been realized that sanctuaries for nature must be allowed to exist in peace and tranquility, that visitation must be curbed and the observation of wildlife be discreet and cautious. But we continue to set visitor records year after year.

In the late 1960s the Ceylon Tourist Board proposed a string of hotels along the Yala coast. The Wildlife Protection Society (presently WNPS: see p.162) opposed this, and in general the setting up of special tourist facilities within National Parks. They argued that for good reasons only the State, through the Wildlife Department, should provide and operate visitor amenities in conservation areas.

There was a conference on the issue, summoned by the Minister of State – the Wildlife Department was then under this Ministry – J. R. Jayewardene. Thilo spoke for the Society as its Honorary Secretary. Eventually their view prevailed, when the Minister decided that hotels cannot be built and operated inside protected areas.

As Thilo was driving off with the President of the Society, E. B. Wikramanayake, he was stopped by Upali Senanayake, a member of the Tourist Board and chief promoter of the hotel project. This dialogue followed:

“I don’t see how we can take you [sic], Thilo!”

“What do you mean?”

“We, the Ceylonese.”

“If that is what you feel, Upali, you should not be in tourism!”

Much later, a somewhat similar situation developed in respect of the Gal Oya National Park, when a foreign company wanted to manage parts of it. This too was prevented, with Thilo at the helm of the Society. The principle was reaffirmed that conservation areas are mainly for the people of Sri Lanka and cannot be misused to provide special facilities for tourists or general infrastructure.