Midweek Review

Breaking the Cocoon: The Duality and Unity of a Dancer’s Body

By Dr Saumya Liyanage

Dance is an elusive art form. It is elusive in the sense that any type of dance form uses the human body as its expressive tool, and the art and the artist are one and the same. Dance is in a way similar to the actor’s art because the dancer uses her body as the means of expression. The actor and the dancer share this common ground where their art and the artistic tool are nonetheless inseparable and tightly intertwined. In order to understand the meaning of dance, one may need to separate the dancer’s body from dance but as stated the inseparability of the dancer from dance poses ontological questions as to who the dancer is and what dance is. Therefore, marking a boundary between the body and the work of dance is always blurred.

It is difficult to explain why people dance and how dance is differentiated from non-dance. Celeste Snowber writes that whether we dance and move our bodies, or whether our bodies are static and still, we always dance. She further argues that ‘we are all dancing and as we are all living, whether it is walking or running, swimming or hopping, jumping or being still. There is a dance of blood and fluid circulating in our bodies, and the expressivity of gestures is a daily activity’ (Snowber cited in Leavy, 2018, p. 247). In this analysis, Snowber broadly defines and blurs the distinction between dance and non-dance challenging us to rethink the way we define dance in the contemporary context.

Yet, Sri Lankan dance scholarship is still practised and confined within a particular school of thought that favours dance as a refined, codified body of movement. The learning of dance needs assiduous practice and dedication under a specific training regimen. Moreover, the dancer’s body should be physically trained and aesthetically beautiful to be able to perform and bring meanings to spectators. Hence traditional dance training and performance is purely cultivated through guru-shishya parampara (Teacher-disciple model) where the repetition and execution of learnt scores are supremely important. Very little space is allowed for the novice to explore physical possibilities beyond the regimented body. However, I am not skeptical about the skills and capacities that a traditional dancer possesses. Yet, this long assiduous practice and the regimentation of bodies along with cosmic teaching pertaining to demons and deities would undoubtedly affect and discipline not only the learner’s physicality but their thought process as well. Therefore, these pedagogical systems do not allow the learner to explore various expressions or movement culture.

In this article, I am going to discuss about an emerging dancer and choreographer Kanchana Malshani and her recent work titled, Talking Silambu performed, at the Royal Taprobanian cultural hub in Navinna, Maharagama. In this piece of dance work, Kanchana raises several questions worthy of discussion through the current practice of dance pedagogy in Sri Lanka and ontological questions of what dance is, and who a dancer is. Further her work explores how dance can be a self-exploratory journey for those who seek alternative avenues through breaking their links to traditional forms and regimented bodies.

Kanchana

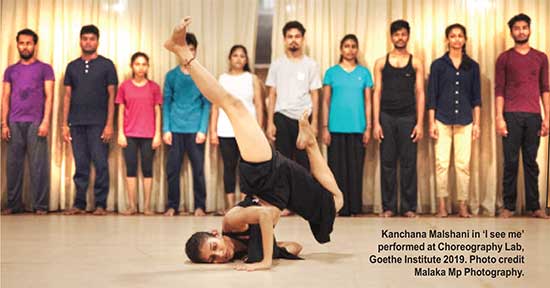

In 2017, Goethe Institute organised a Choreography Lab with dancer Venuri Perera, in Kalpitiya Sri Lanka. At this particular dance lab, Kanchana learnt contemporary dance from Yuko Kaseki, a Japanese Bhuto dancer, and Mahesh Umagiliya. Further, she learnt from Prof. Sandra Mathern-Smith, Professor of dance at Denison University, the USA, who has travelled several times to Sri Lanka as a Fulbright scholar. Her intervention in popularising and mentoring Sri Lankan dancers included a group of students at the University of the Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo, Sripalee campus, was also a turning point in her dance career. Dance teachers like Deepak Kurki Shivaswamy, Preethi Athreya, Maria Colusi have also helped Kanchana develop her skills. After receiving a half scholarship to visit a two-week-long dance camp at Sanskar Dance Festival India, she has been able to work with teachers such as Vittoria de Ferrari Sapetto and Roberto Olivan. Apart from her dance training, Kanchana has been working with one of the English Theatre companies, Stages Theatre, led by writer and director Ruwanthie De Chickera in Colombo. Kanchana may have undoubtedly learnt the value of being an artiste and professionalism in theatre through working in an actors’ ensemble at Stages Theatre.

Dance and Contemporaneity

Yet, these auto-ethnographic or auto-biographical narratives finally gets transformed into a political idiom.

Further contemporary dance deconstructs the aesthetic body celebrated in traditional dance and questions and dissects the skin of the dancer by opening up the inner flesh of the body. André Lepecki further identifies the uniqueness of contemporary dance from other genres because of its ‘ephemerality, corporeality, precariousness, scoring, and performativity’ (Kwan, 2017, p. 39). Thus, contemporary dance does not stick to a particular form, style or a structure. Instead it integrates various techniques, styles, and influences even from traditional dance forms to use the body as a political tool and the self as the centre of expression.

Talking Silambu

In this dance work titled, Talking Silambu, a twenty minute long piece of choreography, Kanchana appears in a non-traditional lose attire while wearing two Silambu (Silambu is a type of anklet made out of brass which Kandyan dancers wear when they perform) In the first instance, we hear the sound of Silambu as Kanchana’s legs begin to move. Yet, her dance body starts movement towards the audience while mixing traditional Kandyan dance codification with free body movement. It is clear that she performs half Kandyan and half improvised body movements in the score. In other words, her body movements are choreographed through semi-Kandyan codification mixed with free style movements. When the dance intensifies, she removes her Silambu, holding them in her hands and begins to shake them with vigorous body movements while throwing her body in various directions. At this point, Kanchana uses a trans-like act depicting trans-performance inherited particularly in low country devil dance. In this work, it is clearly demonstrated that her body is struggling with Silambu and trying to remove its connection to the body. This struggle culminates in the final phase of the dance work by indicating she runs away from the codified body and becomes a free woman. In this work, Kanchana demonstrates her discontent with the previous life as a traditional dancer and her struggle to break her affinity to the codified structure and beautification of the body in Kandyan dance. In a short conversation I had with Kanchana, she mentioned as particular rebirth that occurred at a dance camp organised by the Goethe Institute Colombo:

“I have been trained as a traditional dancer since my childhood but for the first time, working with this Japanese Butoh dancer, Yuko Kaseki, I learnt how to speak from my body. For many years I was living in a cage-tradition where I was entrapped. Living in this cage, I have performed what others wanted me to do. But in this dance lab, I found myself speaking to my own body and speaking through the body. I don’t want my body to be beautiful and aesthetically refined. I don’t want to display precision and codification of my body. I want to show how ugly I am and how vulnerable my body is.” (Kanchana, M., Pers. Comm. Dec. 2020).

Against the grain

Living in an ocular centric world, the dancer’s outer body is a place where womanhood is exploited for commercial purposes. From state-sponsored national festivals to television advertisements selling instant noodles or carbonated drinks, the dancer’s outer skin is commodified. Writing about Sri Lankan neo-dance traditions, propagated and performed at high profile delegations, product launches and in TV commercials in the country, I have written elsewhere that ‘women’s bodies succumb to the surgical knife of the choreographer whose male sexual desires are displayed on those bodies. Hence, no difference can be made between a choreographer and a cosmetic surgeon, whose expertise on women’s bodies, especially breasts and buttocks, are surgically transplanted and enhanced by incisions, stitches and staples’ (Liyanage, 2016). Amidst this commodification of female bodies in Sri Lankan dance arena, Kanchana’s attempt is to break away from this commodified, sexualised, and mechanised body to establish a non-codified and unified body of self-expression.

Here it is important for contemporary dancers to understand the value of the ‘living body’ or the ‘lived’ body that is celebrated in the vast literature of phenomenology and dance theory in the contemporary dance literature. In the dominant dance cultures from stage performances to digital and visual representations, the dancer’s skin is the most valued and emphasised. Now, with the contemporary dance turn, the dancer’s living or lived experience has come forth. Kanchana as a dancer now understands that her body is not a place for others to communicate vague meanings but a living entity where her own selfhood is reflected and displayed. It is a challenge for a dancer like her because the dominant female body has already been already established by key dance authors of the country. These dance authors have created a symbolic and sexualised female body for live and digitised performances. This symbolic and sexualised female body consists of the idealised female body for the male viewer. Kanchana is challenging this idealised body that is dominant in the real and digital world.

Dancer and Danced

The key juncture where the lived body differs from the symbolic body is that the symbolic body that is propagated in the media and elsewhere is the body that is not presented as a place for knowledge. Let me explain this further. In the traditional dance pedagogy, the dancer’s body is a place where meanings are generated and shared. In other worlds, the codified body is a canvas or a display where the onlooker extricates meanings. This codified, symbolic body is not presented to us as a place for knowing or sensing. Kanchana’s work and the work of other contemporary dancers suggest that we should understand the body as a place of sensing and knowing. This marks an epistemological turn in dance making and its reception. Dance, or the dancer’s body, has not been considered a place for ‘knowing’ in Sri Lankan dance pedagogy. Most often, a dancer narrates someone’s story or represents a third person singular perspective of the dance.

What Kanchana and the contemporary dance body suggest is to make a shift from the third person singular narrative to a first person singular perspective. This ‘I’ or the first person perspective allows the dancer to narrate her own stories and engagement with the social, cultural and political terrains. Further, a dancer as the author of her own work marks the departure of the dancer as an employer for a particular author. What Kanchana does in Talking Silambu is that as a dancer she tries to incarnate herself and narrate a story of searching a breakthrough and liberation. In this performance, her body works as a site of struggle and seeks the unity of her body and soul.

Conclusion

Understanding the body as a sensing and perceiving entity is still an alien concept to dance pedagogies in universities and private schools. Furthermore, dance can be a self-expressive and auto-ethnographic inquiry and is also a far-reaching idea for our students. Hence, the mainstream dance pedagogy produces dancers who dance without self-motivation to satisfy the audience who come to see symbolic representation of the body. Yet a handful of dancers who are eagerly exploring other avenues for dance expressions are also facing complex issues that their artistic interventions are not fully accepted in the mainstream dance scholarship in the country. Moreover, dancers like Kanchana have chosen a non-popular pathway to pursue their future dance careers and already faced deadlocks, as their artistic practices are not being accepted or sustained by institutions or organisations. Yet Kanchana is determined to break her cocoon to be incarnated as a hybrid moth.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama and Sachini Senevirathe for their assistance in preparing this paper. Further the author’s gratitude goes to dancer Kanchana Malshani.

References

Kwan, S. (2017). When Is Contemporary Dance? Dance Research Journal, [online] 49(3), pp.38–52. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/dance-research-journal/article/when-is-contemporary-dance/8D44743A01A1ECC8100C5E65C1142DC2 [Accessed 4 Oct. 2019].

Leavy, P. (2019). Handbook of arts-based research. New York: The Guilford Press.