Midweek Review

Brahmi on Potsherds in Anuradhapura

#uதுකම් (#Duty):

By Laleen Jayamanne

Somewhere online, I found this simple but startling composite, multi-scripted, word-slogan of the aragalaya; (#duty#යුතුකම්). Written with letters (akshara), drawn from all three languages of the country, it appears to be by an anonymous artist during the earlier GOTAGOGAMA PHASE of the aragalaya. It’s a key word expressing an ethical sentiment addressing all Lankans at this moment of political and economic upheaval and momentous social transformation.

The longer I look at this strange word many thoughts flash through my mind, though I don’t know Thamil. The letters of the three languages sit close to each other in amity. No hint here that that ‘u’ could cut like a ‘kaduwa’ (sword), or that the Thamil letter might be tarred or that Sinhala is allied to the word sinhaya (lion). Rather, this linguistic sign, as I see it, suggests a desire at the heart of an ethical impulse of the aragalaya (the struggle), a desire for a multi-ethnic Sri Lanka, free of ethno-linguistic-religio-supremacist nationalist violence. But, the fact that the word itself is Sinhala points to the obvious, the taken for granted centrality of the Sinhala folk in the aragalaya. A Tamil letter has also been dutifully included. As for the presence of the English ‘u’, it goes without saying.

It’s just one little word-image, but silently it does speak volumes about non-violence, avihimsa, which has never been part of Lankan political vocabulary, until the Aragalaya made it so. Despite the Buddhist idea of non-violence, Gandhi’s political idea was never a part of Lankan politics in the way it was for Martin Luther King in defining the non-violent ethos of the American Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Few know that Gandhi’s friend Tagore came to Ceylon in 1933 to open Sri Pali (modelled on Shantiniketan), and had spent time in Kandy completing Char Adhyay (Four Chapters) which was his poetic critique of the fascist turn in the Indian independence movement in Bengal. Young freedom fighters went on killing sprees while also

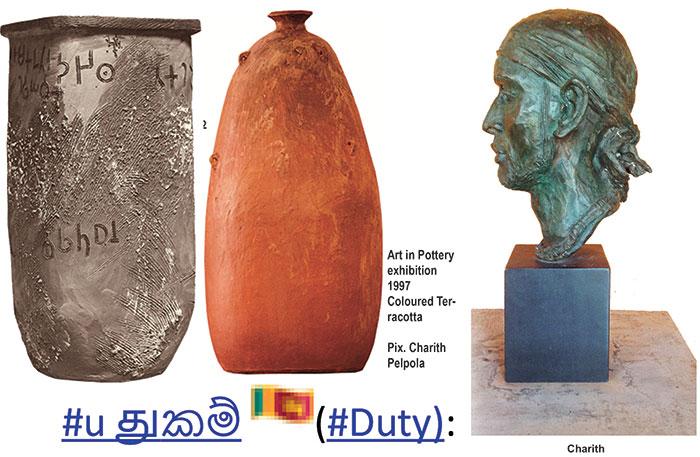

Words and Clay

“Ceramics is the memory of human kind,” Speaking Volumes: Pottery and Words. Paul Mathieu

Kumbha in Sanskrit means pitcher, jar, pot and Kumbha-karaka is a maker of pots. ‘Kumbal’ in Sinhala is also the caste name of potters. If we knew the etymology of the word it would conjure up a well-crafted pot rather than a low status caste, according to feudal Sinhala custom. A pot is useful, and also considered a symbol of the womb in some religious rituals as in the Kumbha-mela in India celebrating the life giving powers of Ganga nam ganga. I don’t know whether a pot carries this symbolic meaning in traditional Sinhala Buddhist culture and ritual as well. In addition to the every-day use-value, and extra-daily ritual-value of pottery, Paul Mathieu draws out the civilizational link between pottery and writing with its powerful abstract-value.

“The relationships between ceramics and text, pottery and words, are very old and very new. These relationships may not be too obvious at first, but it is my intent to show here that there is a very intimate connection between clay and language, ceramics and the written text, and that this symbiosis between the two cultural phenomena is very ancient and profoundly meaningful. Much has been made of the use of words and text in art and in contemporary culture, especially in new media technologies, but that has been true of ceramic objects since the very beginning of recorded history.

The earliest examples of ceramic objects related to language and writing are clay tokens from Mesopotamia dating from 8000 B.C. (see Schmandt-Besserat, Before Writing). These tokens were part of an accounting system used in exchange and commercial transactions.” Paul Mathieu

In Search of Lost Time

Closer to home, when reading several obituary tributes to the distinguished Lankan archaeologist, Siran Upendra Deraniyagala, in 2021, I learnt about his many remarkable achievements. Foremost among these is the unearthing, in the late 80s, in Anuradhapura, of potsherds inscribed with the Brahmi script. These were radiocarbon dated to about 4th or 5th Century BCE, confirmed by a team from Cambridge University and later corroborated by similar findings in Tamil Nadu. It is considered to be the earliest known script in South Asia. This dates the Brahmi script to about a century or two before Mahinda Thera, the son of Asoka, brought Buddhism to Sri Lanka, during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa, in 3rd Century BCE. While the epigraphs on the famous Asokan pillars across India are also inscribed in Brahmi, the form discovered in Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu are considered to be of a much earlier variant of the script. As such, linguists consider it to be the ancestor of several modern vernacular scripts in the region. This period is described as proto-history, the script pointing to a literate culture and trade links with both India and beyond in West Asia, prior to the arrival of Buddhism. With such a long history, proto-history and pre-history recorded also in the palaeo-archaeology of Paul Deraniyagala, Siran Deraniyagala’s father, we have been given a powerful vision of temporal-duration of this little Island home of ours, at the tip of the Indian subcontinent, initially geologically linked to it.

Brahmi Script and the Aragalaya

The early period of the Aragalaya felt like an auspicious moment to explore some aspects of the implications of the ‘earth shattering’ Deraniyagala discovery, beyond the highly specialised domain of archaeology. One hopes that the chauvinist fear (of finding evidence in the depths of the earth’s womb, which might dispel the myth of Sinhala-Buddhist ‘manifest destiny’), might be dispersing. Pottery with writing is on another level or stratum from the fossil record. It helps to calculate time and value in relation to the development of human culture, specifically, the expansion of its powers of abstraction. The creation of a heady variety of abstract visual lines on clay, corresponding to sounds and meanings, makes language and drawing tantalisingly close to each other. Writing is linear and formalised into sound and meaning; language. Whereas, ‘line-drawing’ appears to activate a vagrant line. Or to put it differently, a line drawn by an artist moves without a known destination; art. On one hand, an encoding of the line precisely, on the other, a freeing of the idea of the line, which carries us away into the unknown.

“Dr. must be the most influential archaeologist in Sri Lanka after Prof. Senarth Paranavitana. Introducing a new historical paradigm to the Sri Lankan past, undoubtedly, it was only he who presented a systematic – theoretical framework to the Sri Lankan past and tested a hypothesis through several decades until it developed into general acceptance. The results of the quest have been momentous.

If someone seriously examines his landmark publication of 1992, they will be able to find a road map to the future studies and pointers to raise new questions.” Thilanka Siriwardana, (Archaeology.lk)

Deraniyagala, SU, 1984, “A classificatory system for ceramics in Sri Lanka”. Ancient Ceylon 5, 109- 114.

Art and Ecologycal Consciousness

Maybe, some contemporary artists with an interest in science and ecological thinking might feel like glancing at the fossil collection of Paul Deraniyagala in our katuge (House of Bones or Museum!) and who knows where that might lead! There might be a lateral connection to be made between Siran Deraniyagala’s momentous archaeological discoveries in Anuradhapura, of potsherds with the Brahmi script inscribed on them, and that of his father’s archaeo-paleontology and physical anthropology! This may appear to be a fanciful idea, but it is the case that artists working in the new media, including musicians are now working with scientists, at places like MIT, Cornel University and elsewhere, to develop projects, in the broad area of ecological thinking, that require collaborative team work across disciplines and skills. Ecological thinking now also includes, what Felix Guattari the psycho-therapist called, ‘mental-ecology’. Such collaboration may give artists with an ecological bent some lateral ideas to think with about interrelations of script (as movement), language (as sound), ethnicity, material culture, custom, the human body, nature and technology as ‘second-nature’, in Sri Lanka’s pre-history and proto-history, as they might relate to contemporary concerns. Siran Deraniyagala’s dig at Anuradhapura was 30 feet below ground level and it is said that he only uncovered a fraction of what is thought to be there. Can we imagine (certainly not another myth of origin of the lion race of the Sinhala), other ways of understanding the interconnectedness of all life forms and minerals, ‘transversally’, rather than hierarchically on this ancient island situated so propitiously on east west trade routes?

Siran U Deraniyagala, The Prehistory of Sri Lanka; An Ecological Perspective, (Colombo: Dept. of Archaeology, Government of Sri Lanka, 1992).