Sat Mag

After Bandung: Marxism’s exit from the Third World

On 18 April, exactly 65 years ago, the Bandung Conference took place with the participation of 29 countries, almost all of them ex-colonies. This is the first in a series of essays examining the Conference, the Non-Aligned Movement, and their eventual dissolution.

By Uditha Devapriya

The postmodernist intellectuals of continental Europe who grew up adulating Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin had, by the time they left university and become policymakers or thinkers (or both), grown cynical of them. Ernest Mandel characterised the post-World War II order as ‘late capitalist’. I make this point because it’s futile to deny the parallels between the intellectual trajectory of postmodernist movement and the path capitalism took during this period. That link, as it stands, is essential to any critique of postmodernism.

Postmodernists, especially Foucault, Baudrillard, and Lyotard, gradually came to believe in the futility of political confrontation, and substituted notions of discourse and hegemony – the latter ‘borrowed’ from Gramsci – for the more fundamental dynamic of labour and class relations, which, after all, is what Marxism is supposed to be about. Frederic Jameson’s famous description of postmodernism as “the cultural logic of late capitalism” must be seen in this light; in shying away from political confrontation, he argued, it had succeeded in abdicating from its rightful task and sustaining the status quo.

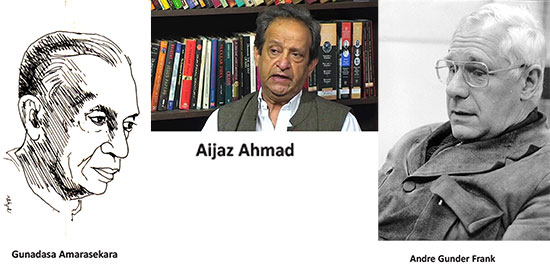

Jameson wasn’t alone. Terry Eagleton and Christopher Norris made the same critique, from a different perspective. So did Ihab Hassan, Immanuel Wallerstein, Jurgen Habermas, Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank, and Aijaz Ahmad. Samir Amin and Gunder Frank, while basically disagreeing with one another, agreed that postmodernism, under the pretext of offering an alternative to Marxism, cut off the debate over disparities of wealth, income, and power from its working class, economic roots. Particularly in the Third World.

Aijaz Ahmad wrote of the emergence of a new intellectual movement, among Third World émigrés in the West, which “continued to call itself a formation of the left” while removing itself from the labour movement and at the same time invoking “an anti-bourgeois stance.” For Ahmad, this movement, an outcome of the continuous pummelling of anti-imperialist thought by the political right in the West, got propped up in the name of similar movements like anti-empiricism, structuralism, and post-structuralism. This critique of postmodernism, the most relevant yet to the Third World, continues to be made even today. But for every such critic and critique, there is always a fellow traveller.

Edward Said adopted Foucault’s notion of ‘discourse’ as the foundation for his critique of orientalism. As much as I am inclined to believe in what Orientalism talks about, at times Said comes across as an anti-ideological intellectual who finds in the very discussion of the orient by Westerners their supposedly condescending attitude to the East. As Irfan Habib, no opponent of Said, once asserted, “Said’s concept of ‘orientalism’ is both far too general and far too restricted,” general since it can cover anyone who professes to talk and write on the topic, and restricted since by doing so, it excludes the possibility of discussion about the orient by Westerners who are not Orientalists.

However, my critique of Orientalism, and Said’s name-calling, goes much deeper than that. My issue with Orientalism is that Said conflates Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami, both neo-conservatives who supported Bush’s crusades in the Middle East, with Karl Marx, the latter “dismissed in the book as another orientalist.” I have my take on how Marxists, particularly European Marxists, viewed the problems of the Third World. They were, to be sure, Eurocentric, and fundamentally of the belief that ex-colonies required bourgeois democratic revolutions; a grave misreading of the ground reality, given the inability of bourgeois elites in ex-colonies to carry forward any such revolution even within the framework of a Non-Aligned Movement.

Said’s reading of Marx’s position on India, though, does not follow this critique, or even reproduce it. Instead he suggests that Marx, like the orientalists he targets, ‘otherised’ the people of the Third World with his argument that colonialism sped up the destruction of feudalism; in essence, that India needed Britain to help destroy its superstitions and feudal practices, just as Iraq, in the eyes of Lewis and Ajami, needed Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld to escape the clutches of a brutal quasi-medieval dictatorship.

The point I’m trying to make is that Said, while offering a radical reading of how politics, economics, literature, and art and culture, (the latter’s impact on Orientalism explored in greater depth 15 years later in Culture and Imperialism), shape the First World’s view of the Third, turns the tables on Marxism itself. He doesn’t do so from the vantage point of Left theorists like Amin and Gunder Frank. He does so from the vantage point of postmodernism: Foucault and his notion of discourse, which writes off all “grand narratives” as domineering, and writes off Marxism since, like capitalism, it domineers.

Amin and Gunder Frank didn’t turn Marxism on its head as much as critique communist theorists for misunderstanding the ground situation in the Third World, especially in their support for the Non-Aligned Movement (read, in particular, Amin’s essay “The Bourgeois National Project in the Third World”). Yet they were critical of postmodernists also, whom they saw in the same light vis-à-vis Jameson, Eagleton, and Norris. I believe their rebuttal of the movement offers us a nuanced reading of it that can help us understand, more clearly, how it came to subsume the Marxist movement in the Third World.

Amin and Gunder Frank didn’t turn Marxism on its head as much as critique communist theorists for misunderstanding the ground situation in the Third World, especially in their support for the Non-Aligned Movement (read, in particular, Amin’s essay “The Bourgeois National Project in the Third World”). Yet they were critical of postmodernists also, whom they saw in the same light vis-à-vis Jameson, Eagleton, and Norris. I believe their rebuttal of the movement offers us a nuanced reading of it that can help us understand, more clearly, how it came to subsume the Marxist movement in the Third World.

Historically, postmodernism has viewed Marxism as part and parcel of the Enlightenment. It regards the Enlightenment, not as an emancipatory movement, but as a restrictive ideology which bound everyone to a rational worldview. What flows from that line of thinking is the claim that Marxism originated from the same Western Judeo-Christian worldview capitalism had: both, after all, happened to be driven by “the hubris of dedication to man’s mastery over nature” (Regi Siriwardena). This observation, sceptical as it is of the ‘internationalist’ character of Marxism, is made by rightwing ethno-nationalists as well.

Thus the most typical and frequently invoked critique of Marxism by the postmodernists is that it belongs in the same vein as bourgeois thought to the Enlightenment. A corollary of that critique is that Marxism reduces everything to class struggle; communism and socialism are therefore indicted as assuming that everything falls down to class relations. I disagree with such a stereotype: as Jason Schulman once pointed out, “for Marx the fundamental human category is not class struggle, but labour.” Indeed, I’d go further than Schulman and say that the fundamental human category for Marx is neither class struggle nor labour, but production, “the basis of social order” according to Marx and Engels.

But valid as this counter-response is, it still doesn’t resolve another complaint: that Marxism rationalises everything in economic terms. Postmodernists contend that this underlies its quintessential flaw: its rigidly economistic interpretation of history, which views all societal arrangements through the prism of material relations.

The flaw is followed by a contradiction: to topple a social order and the basis for it, power has to pass from the top of society to its bottom.

Yet the transition can only be carried out through a bourgeois revolution, by the bourgeoisie at the top. This orthodox Marxist reading of history lured much of the Third World, including Egypt and, to a certain extent, Sri Lanka, which explains why, in part at least, the Non-Aligned Movement failed: much of the Third World that emerged from Bandung 1955 happened to be led by the same nationalist elites who later contributed to the deterioration of their countries, and of NAM, due to their inability to take the revolution in their streets beyond the bourgeois-democratic stage.

Liberating and progressive as they were, towards the end of their terms, leaders like Nasser had become adamantly opposed to the incorporation of radical Left elements. In Sri Lanka this culminated in the expulsion of the Trotskyist LSSP in 1975 (the same year the Group of 77 supported New International Economic Order attempted, and failed, to integrate the Third World into the global economy) and the entrenchment of the right wing of the SLFP, leading to their defeat by the UNP in 1977. As with Sri Lanka, so with Egypt: the dissolution of Communist parties in 1965 was followed two years later by the catastrophic defeat of the June war. By 1982, with Mexico’s debt default, NAM had more or less unravelled; with much prescience could J. R. Jayewardene thus declare, at the 1979 Havana Summit, that the only nonaligned countries in the world were “the United States and the Soviet Union.”

Development economists, theorising against the backdrop of the Third World debt crisis and the ‘triumph’ of neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism, as well as the collapse of the Non-Aligned Movement, thought they had the solution to this problem. They reasoned that the intelligentsia, as opposed to the elite, should be tasked with ‘delinking’ underdeveloped countries from the clutches of capitalism. In their opinion the rulers had failed, miserably (“the regimes were nothing but bourgeois,” wrote Samir Amin); the time had come for the baton to pass from them to the professors.

Later events confirmed that this solution turned out to be more flawed than the one they chose to discard. Why? Their solution was rooted in a critique of capitalism that first had to lay bare its contradictions and then transcend it. “The critique,” Samir Amin emphasised, “is meaningless unless it sharpens our awareness of the limitations of bourgeois thought.” But the intelligentsia on whom this task fell, at the time Amin wrote his prognosis, had changed, and its capacity to take on that task of critiquing the capitalist framework, and transcending it, had diminished. Just as the professors no longer adhered to orthodox Marxism, they also no longer opposed globalisation. There’s no other reason why the dependenistas, as Gunder Frank and Amin were called, failed in their project than this.

To understand why and how, it’s necessary to go back. Throughout the 1960s, Third World immigration to the West swelled considerably. This happened to transpire at the peak of the Bandung Project, when much of the nonaligned world as Fouad Ajami later put it seemed buoyed by the “enthusiasm of youth.” Ajami himself soon made his way to Western citadels of learning; so did Ranajit Guha, and so did Edward Said.

Because of that intellectual shift, the 1970s became a productive period for studies of the Left, feminism, and development in the Third World. Gunder Frank and Samir Amin were at the forefront here, along with George Beckford (Persistent Poverty), Eduardo Galeano (Open Veins of Latin America), Gordon K. Lewis (The Growth of the Modern West Indies), Eric Williams (From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean), and Kumari Jayawardena (The Rise of the Labour Movement in Ceylon). S. B. D. de Silva spent the better part of the decade collecting his thoughts for the most perceptive analysis of Sri Lanka’s economy ever written: The Political Economy of Underdevelopment, first published in 1982.

As Aijaz Ahmad correctly observed, many of these academics hailed from the upper classes of their societies. They would have cut a poor figure in the West, but back home they were eagerly sought after as experts by their governments for the formulation of economic and foreign policy, against the backdrop of a rising New Third World. (NAM was yet to enter its twilight years.) Most of these émigré intellectuals managed, in their new role as Third World policymakers, to escape their largely non-working class social background. Many could not. This paradox, between their social class and their status as Third World intellectuals, did not come out into the open just yet.

But then the 1970s would give way to the 1980s. That decade saw the resurgence of neo-liberalism in the person of Thatcher, Reagan, and before them, J. R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka. In much of the Third World, the transition to ‘free markets’ invariably accompanied brutal centralisations of power by the political Right as well as assaults on the Left (including on trade unions, as seen in July 1980 in Colombo), and, concurrently, the rise of a parallel non-state sector; I call the latter ‘civil society’ in deference to a classification favoured by most scholars. Émigré intellectuals, some of whom had worked in the public sector, now found their place in the sun in that non-state sector.

Accompanying all this was the rise of an alternative non-Marxist discourse, fuelled in part by these émigrés from the West who were now writing on orientalism (Said), Islamism (Ajami), and subalterns (Guha). While not giving up on their Marxist roots, many of these émigrés repudiated – sometimes rightly, often wrongly – the tenets of Marxism. Some, like Ajami, sold themselves out to neo-cons, becoming what Adam Shatz of The Nation calls “the native informant.” Others, like Said, tried to achieve a balancing act, veering away from Ajami’s pro-Western polemics and from fundamentalist groups which would gain prominence after the 1980s. These three ideological formations – neo-conservatism (Ajami), post-Marxist humanism (Said), and cultural revivalism – soon began to brandish swords at one another; no common ground ever brought them together thereafter.

Save, of course, for one: their sidelining of Marxism.

The intrusion of postmodernism in the Third World can thus be viewed in the same light as the resurgence of nationalism on the one hand and the triumph of neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism on the other, given their mutual aversion to the Left. The dismissal of Marxism by Third World émigré intellectuals can be considered, in that sense, as having facilitated the rise of anti-Marxist nationalist as well as post-Marxist postmodernist groups throughout much of this part of the world, particularly in Africa and South Asia.

Certainly, it is one of the ironies of history that the same anti-Marxist discourse which gave birth to communal-nationalist outfits could also, later, give birth to post-Marxist intellectual movements opposed to them. These have become, to borrow that memorable but worn out cliché, two sides of the same coin, or the same sword. The triumph of postmodernism in the Third World today has hence led to both sides – civil society and ethno-nationalists – gaining at the cost of the most progressive ideology we have ever come up with: Marxism. I called this one of history’s ironies. It is also, most certainly, one of its tragedies.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Sat Mag

Living building challenge

By Eng. Thushara Dissanayake

The primitive man lived in caves to get shelter from the weather. With the progression of human civilization, people wanted more sophisticated buildings to fulfill many other needs and were able to accomplish them with the help of advanced technologies. Security, privacy, storage, and living with comfort are the common requirements people expect today from residential buildings. In addition, different types of buildings are designed and constructed as public, commercial, industrial, and even cultural or religious with many advanced features and facilities to suit different requirements.

We are facing many environmental challenges today. The most severe of those is global warming which results in many negative impacts, like floods, droughts, strong winds, heatwaves, and sea level rise due to the melting of glaciers. We are experiencing many of those in addition to some local issues like environmental pollution. According to estimates buildings account for nearly 40% of all greenhouse gas emissions. In light of these issues, we have two options; we change or wait till the change comes to us. Waiting till the change come to us means that we do not care about our environment and as a result we would have to face disastrous consequences. Then how can we change in terms of building construction?

Before the green concept and green building practices come into play majority of buildings in Sri Lanka were designed and constructed just focusing on their intended functional requirements. Hence, it was much likely that the whole process of design, construction, and operation could have gone against nature unless done following specific regulations that would minimize negative environmental effects.

We can no longer proceed with the way we design our buildings which consumes a huge amount of material and non-renewable energy. We are very concerned about the food we eat and the things we consume. But we are not worrying about what is a building made of. If buildings are to become a part of our environment we have to design, build and operate them based on the same principles that govern the natural world. Eventually, it is not about the existence of the buildings, it is about us. In other words, our buildings should be a part of our natural environment.

The living building challenge is a remarkable design philosophy developed by American architect Jason F. McLennan the founder of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI). The International Living Future Institute is an environmental NGO committed to catalyzing the transformation toward communities that are socially just, culturally rich, and ecologically restorative. Accordingly, a living building must meet seven strict requirements, rather certifications, which are called the seven “petals” of the living building. They are Place, Water, Energy, Equity, Materials, Beauty, and Health & Happiness. Presently there are about 390 projects around the world that are being implemented according to Living Building certification guidelines. Let us see what these seven petals are.

Place

This is mainly about using the location wisely. Ample space is allocated to grow food. The location is easily accessible for pedestrians and those who use bicycles. The building maintains a healthy relationship with nature. The objective is to move away from commercial developments to eco-friendly developments where people can interact with nature.

Water

It is recommended to use potable water wisely, and manage stormwater and drainage. Hence, all the water needs are captured from precipitation or within the same system, where grey and black waters are purified on-site and reused.

Energy

Living buildings are energy efficient and produce renewable energy. They operate in a pollution-free manner without carbon emissions. They rely only on solar energy or any other renewable energy and hence there will be no energy bills.

Equity

What if a building can adhere to social values like equity and inclusiveness benefiting a wider community? Yes indeed, living buildings serve that end as well. The property blocks neither fresh air nor sunlight to other adjacent properties. In addition, the building does not block any natural water path and emits nothing harmful to its neighbors. On the human scale, the equity petal recognizes that developments should foster an equitable community regardless of an individual’s background, age, class, race, gender, or sexual orientation.

Materials

Materials are used without harming their sustainability. They are non-toxic and waste is minimized during the construction process. The hazardous materials traditionally used in building components like asbestos, PVC, cadmium, lead, mercury, and many others are avoided. In general, the living buildings will not consist of materials that could negatively impact human or ecological health.

Beauty

Our physical environments are not that friendly to us and sometimes seem to be inhumane. In contrast, a living building is biophilic (inspired by nature) with aesthetical designs that beautify the surrounding neighborhood. The beauty of nature is used to motivate people to protect and care for our environment by connecting people and nature.

Health & Happiness

The building has a good indoor and outdoor connection. It promotes the occupants’ physical and psychological health while causing no harm to the health issues of its neighbors. It consists of inviting stairways and is equipped with operable windows that provide ample natural daylight and ventilation. Indoor air quality is maintained at a satisfactory level and kitchen, bathrooms, and janitorial areas are provided with exhaust systems. Further, mechanisms placed in entrances prevent any materials carried inside from shoes.

The Bullitt Center building

Bullitt Center located in the middle of Seattle in the USA, is renowned as the world’s greenest commercial building and the first office building to earn Living Building certification. It is a six-story building with an area of 50,000 square feet. The area existed as a forest before the city was built. Hence, the Bullitt Center building has been designed to mimic the functions of a forest.

The energy needs of the building are purely powered by the solar system on the rooftop. Even though Seattle is relatively a cloudy city the Bullitt Center has been able to produce more energy than it needed becoming one of the “net positive” solar energy buildings in the world. The important point is that if a building is energy efficient only the area of the roof is sufficient to generate solar power to meet its energy requirement.

It is equipped with an automated window system that is able to control the inside temperature according to external weather conditions. In addition, a geothermal heat exchange system is available as the source of heating and cooling for the building. Heat pumps convey heat stored in the ground to warm the building in the winter. Similarly, heat from the building is conveyed into the ground during the summer.

The potable water needs of the building are achieved by treating rainwater. The grey water produced from the building is treated and re-used to feed rooftop gardens on the third floor. The black water doesn’t need a sewer connection as it is treated to a desirable level and sent to a nearby wetland while human biosolid is diverted to a composting system. Further, nearly two third of the rainwater collected from the roof is fed into the groundwater and the process resembles the hydrologic function of a forest.

It is encouraging to see that most of our large-scale buildings are designed and constructed incorporating green building concepts, which are mainly based on environmental sustainability. The living building challenge can be considered an extension of the green building concept. Amanda Sturgeon, the former CEO of the ILFI, has this to say in this regard. “Before we start a project trying to cram in every sustainable solution, why not take a step outside and just ask the question; what would nature do”?

Sat Mag

Something of a revolution: The LSSP’s “Great Betrayal” in retrospect

By Uditha Devapriya

On June 7, 1964, the Central Committee of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party convened a special conference at which three resolutions were presented. The first, moved by N. M. Perera, called for a coalition with the SLFP, inclusive of any ministerial portfolios. The second, led by the likes of Colvin R. de Silva, Leslie Goonewardena, and Bernard Soysa, advocated a line of critical support for the SLFP, but without entering into a coalition. The third, supported by the likes of Edmund Samarakkody and Bala Tampoe, rejected any form of compromise with the SLFP and argued that the LSSP should remain an independent party.

The conference was held a year after three parties – the LSSP, the Communist Party, and Philip Gunawardena’s Mahajana Eksath Peramuna – had founded a United Left Front. The ULF’s formation came in the wake of a spate of strikes against the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government. The previous year, the Ceylon Transport Board had waged a 17-day strike, and the harbour unions a 60-day strike. In 1963 a group of working-class organisations, calling itself the Joint Committee of Trade Unions, began mobilising itself. It soon came up with a common programme, and presented a list of 21 radical demands.

In response to these demands, Bandaranaike eventually supported a coalition arrangement with the left. In this she was opposed, not merely by the right-wing of her party, led by C. P. de Silva, but also those in left parties opposed to such an agreement, including Bala Tampoe and Edmund Samarakkody. Until then these parties had never seen the SLFP as a force to reckon with: Leslie Goonewardena, for instance, had characterised it as “a Centre Party with a programme of moderate reforms”, while Colvin R. de Silva had described it as “capitalist”, no different to the UNP and by default as bourgeois as the latter.

The LSSP’s decision to partner with the government had a great deal to do with its changing opinions about the SLFP. This, in turn, was influenced by developments abroad. In 1944, the Fourth International, which the LSSP had affiliated itself with in 1940 following its split with the Stalinist faction, appointed Michel Pablo as its International Secretary. After the end of the war, Pablo oversaw a shift in the Fourth International’s attitude to the Soviet states in Eastern Europe. More controversially, he began advocating a strategy of cooperation with mass organisations, regardless of their working-class or radical credentials.

Pablo argued that from an objective perspective, tensions between the US and the Soviet Union would lead to a “global civil war”, in which the Soviet Union would serve as a midwife for world socialist revolution. In such a situation the Fourth International would have to take sides. Here he advocated a strategy of entryism vis-à-vis Stalinist parties: since the conflict was between Stalinist and capitalist regimes, he reasoned, it made sense to see the former as allies. Such a strategy would, in his opinion, lead to “integration” into a mass movement, enabling the latter to rise to the level of a revolutionary movement.

Though controversial, Pablo’s line is best seen in the context of his times. The resurgence of capitalism after the war, and the boom in commodity prices, had a profound impact on the course of socialist politics in the Third World. The stunted nature of the bourgeoisie in these societies had forced left parties to look for alternatives. For a while, Trotsky had been their guide: in colonial and semi-colonial societies, he had noted, only the working class could be expected to see through a revolution. This entailed the establishment of workers’ states, but only those arising from a proletarian revolution: a proposition which, logically, excluded any compromise with non-radical “alternatives” to the bourgeoisie.

To be sure, the Pabloites did not waver in their support for workers’ states. However, they questioned whether such states could arise only from a proletarian revolution. For obvious reasons, their reasoning had great relevance for Trotskyite parties in the Third World. The LSSP’s response to them showed this well: while rejecting any alliance with Stalinist parties, the LSSP sympathised with the Pabloites’ advocacy of entryism, which involved a strategic orientation towards “reformist politics.” For the world’s oldest Trotskyite party, then going through a series of convulsions, ruptures, and splits, the prospect of entering the reformist path without abandoning its radical roots proved to be welcoming.

Writing in the left-wing journal Community in 1962, Hector Abhayavardhana noted some of the key concerns that the party had tried to resolve upon its formation. Abhayavardhana traced the LSSP’s origins to three developments: international communism, the freedom struggle in India, and local imperatives. The latter had dictated the LSSP’s manifesto in 1936, which included such demands as free school books and the use of Sinhala and Tamil in the law courts. Abhayavardhana suggested, correctly, that once these imperatives changed, so would the party’s focus, though within a revolutionary framework. These changes would be contingent on two important factors: the establishment of universal franchise in 1931, and the transfer of power to the local bourgeoisie in 1948.

Paradoxical as it may seem, the LSSP had entered the arena of radical politics through the ballot box. While leading the struggle outside parliament, it waged a struggle inside it also. This dual strategy collapsed when the colonial government proscribed the party and the D. S. Senanayake government disenfranchised plantation Tamils. Suffering two defeats in a row, the LSSP was forced to think of alternatives. That meant rethinking categories such as class, and grounding them in the concrete realities of the country.

This was more or less informed by the irrelevance of classical and orthodox Marxian analysis to the situation in Sri Lanka, specifically to its rural society: with a “vast amorphous mass of village inhabitants”, Abhayavardhana observed, there was no real basis in the country for a struggle “between rich owners and the rural poor.” To complicate matters further, reforms like the franchise and free education, which had aimed at the emancipation of the poor, had in fact driven them away from “revolutionary inclinations.” The result was the flowering of a powerful rural middle-class, which the LSSP, to its discomfort, found it could not mobilise as much as it had the urban workers and plantation Tamils.

Where else could the left turn to? The obvious answer was the rural peasantry. But the rural peasantry was in itself incapable of revolution, as Hector Abhayavardhana has noted only too clearly. While opposing the UNP’s Westernised veneer, it did not necessarily oppose the UNP’s overtures to Sinhalese nationalism. As historians like K. M. de Silva have observed, the leaders of the UNP did not see their Westernised ethos as an impediment to obtaining support from the rural masses. That, in part at least, was what motivated the Senanayake government to deprive Indian estate workers of their most fundamental rights, despite the existence of pro-minority legal safeguards in the Soulbury Constitution.

To say this is not to overlook the unique character of the Sri Lankan rural peasantry and petty bourgeoisie. Orthodox Marxists, not unjustifiably, characterise the latter as socially and politically conservative, tilting more often than not to the right. In Sri Lanka, this has frequently been the case: they voted for the UNP in 1948 and 1952, and voted en masse against the SLFP in 1977. Yet during these years they also tilted to the left, if not the centre-left: it was the petty bourgeoisie, after all, which rallied around the SLFP, and supported its more important reforms, such as the nationalisation of transport services.

One must, of course, be wary of pasting the radical tag on these measures and the classes that ostensibly stood for them. But if the Trotskyite critique of the bourgeoisie – that they were incapable of reform, even less revolution – holds valid, which it does, then the left in the former colonies of the Third World had no alternative but to look elsewhere and to be, as Abhayavardhana noted, “practical men” with regard to electoral politics. The limits within which they had to work in Sri Lanka meant that, in the face of changing dynamics, especially among the country’s middle-classes, they had to change their tactics too.

Meanwhile, in 1953, the Trotskyite critique of Pabloism culminated with the publication of an Open Letter by James Cannon, of the US Socialist Workers’ Party. Cannon criticised the Pabloite line, arguing that it advocated a policy of “complete submission.” The publication of the letter led to the withdrawal of the International Committee of the Fourth International from the International Secretariat. The latter, led by Pablo, continued to influence socialist parties in the Third World, advocating temporary alliances with petty bourgeois and centrist formations in the guise of opposing capitalist governments.

For the LSSP, this was a much-needed opening. Even as late as 1954, three years after S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike formed the SLFP, the LSSP continued to characterise the latter as the alternative bourgeois party in Ceylon. Yet this did not deter it from striking up no contest pacts with Bandaranaike at the 1956 election, a strategy that went back to November 1951, when the party requested the SLFP to hold a discussion about the possibility of eliminating contests in the following year’s elections. Though it extended critical support to the MEP government in 1956, the LSSP opposed the latter once it enacted emergency measures in 1957, mobilising trade union action for a period of three years.

At the 1960 election the LSSP contested separately, with the slogan “N. M. for P.M.” Though Sinhala nationalism no longer held sway as it had in 1956, the LSSP found itself reduced to a paltry 10 seats. It was against this backdrop that it began rethinking its strategy vis-à-vis the ruling party. At the throne speech in April 1960, Perera openly declared that his party would not stabilise the SLFP. But a month later, in May, he called a special conference, where he moved a resolution for a coalition with the party. As T. Perera has noted in his biography of Edmund Samarakkody, the response to the resolution unearthed two tendencies within the oppositionist camp: the “hardliners” who opposed any compromise with the SLFP, including Samarakkody, and the “waverers”, including Leslie Goonewardena.

These tendencies expressed themselves more clearly at the 1964 conference. While the first resolution by Perera called for a complete coalition, inclusive of Ministries, and the second rejected a coalition while extending critical support, the third rejected both tactics. The outcome of the conference showed which way these tendencies had blown since they first manifested four years earlier: Perera’s resolution obtained more than 500 votes, the second 75 votes, the third 25. What the anti-coalitionists saw as the “Great Betrayal” of the LSSP began here: in a volte-face from its earlier position, the LSSP now held the SLFP as a party of a radical petty bourgeoisie, capable of reform.

History has not been kind to the LSSP’s decision. From 1970 to 1977, a period of less than a decade, these strategies enabled it, as well as the Communist Party, to obtain a number of Ministries, as partners of a petty bourgeois establishment. This arrangement collapsed the moment the SLFP turned to the right and expelled the left from its ranks in 1975, in a move which culminated with the SLFP’s own dissolution two years later.

As the likes of Samarakkody and Meryl Fernando have noted, the SLFP needed the LSSP and Communist Party, rather than the other way around. In the face of mass protests and strikes in 1962, the SLFP had been on the verge of complete collapse. The anti-coalitionists in the LSSP, having established themselves as the LSSP-R, contended later on that the LSSP could have made use of this opportunity to topple the government.

Whether or not the LSSP could have done this, one can’t really tell. However, regardless of what the LSSP chose to do, it must be pointed out that these decades saw the formation of several regimes in the Third World which posed as alternatives to Stalinism and capitalism. Moreover, the LSSP’s decision enabled it to see through certain important reforms. These included Workers’ Councils. Critics of these measures can point out, as they have, that they could have been implemented by any other regime. But they weren’t. And therein lies the rub: for all its failings, and for a brief period at least, the LSSP-CP-SLFP coalition which won elections in 1970 saw through something of a revolution in the country.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist based in Sri Lanka who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Sat Mag

50 years of legacy of Police Cadeting at Ananda

By Nilakshan Perera

Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranayake wanted to forge a cordial relationship with school children and the Police Department, after carefully studying a similar programme in Singapore and Malaysia. With the support of the then Ministry of Education and the Sri Lanka Police, the Sri Lanka Police Cadet Corps began as an attachment to the Sri Lankan Police Reserve. On 03 July 1972, six schools were selected for the pilot programme; namely Kingswood College Kandy, Mahinda College Galle, Hindu College Jaffna, Ananda College Colombo, Zahira College Gampola and Sangabodhi Vidyalaya Nittambuwa. By 1978, this number rose to 32 Boys’ schools and 19 Girls’ schools.

Each of these individual platoons consisted of 33 cadets. The masters who were in charge of these platoons were considered part of the Police Reserve. They were assigned with the rank of an Inspector (IP) or a Sub Inspector (SI).

Cadet Corps held a selection for the camps. They would participate in annual competitions for squad drills, physical training, first-aid, drama, billet inspection, general knowledge and public relations, best commander, sports and IGP’s Challenge Shield. From these selection camps, the first three winners would be called for the final camp, from which the Island winner was then selected.

When Ananda College was selected for Police Cadetting on 03 July 1972, two of the school’s teachers were appointed as the Officers In-charge of the College Cadet Platoon. They were Mr Lionel Gunasekera and Mr Ariyapala. Later on, Mr W Weerasekera took over from Mr Ariyapala. Both Mr Gunasekera and Mr Weerasekera extended their invaluable and unwavering services for the Cadet Platoon’s success story. Both these gentlemen were there to supervise and train cadets. One could not forget Mr Weerasekera’s 9 Sri 7321 orange coloured Bajaj scooter parked next to the College main canteen. Another teacher, who trained cadets for drama competitions, voluntarily, was the late Mr Lionel Ranwala. He was the talented master who helped cadets to secure wins in the drama competition, year after year, at the annual camps.

The evening before attending the camp, a special “Mal Pooja” was organised to bless the platoon. After this, they would meet the principal, at his office, for another special blessing and a tea party, hosted by the principal himself. The then Principal of Ananda College, Colonel GW Rajapakse, gave his fullest blessings to the Police Cadets. These recognised cadets earned more responsibilities and assumed various leadership roles at the College. Prefects, Deputy Head Prefect, Head Prefect, Big Match Tent Secretaries, and Presidents of various societies were given to Cadets uncontestedly.

The Cadets stayed at the hostel, the night before leaving for camp. Our trunks were loaded into the college van and unloaded at Maradana Railway station. The most valuable trunk in the Cadet’s eyes was the PLATOON BOX. This was so since the box often contained items such as butter cakes, bottles ofcordial, sweets, such as marshmallows, chocolate rolls, and biscuits. This precious box was kept under lock and key and the watchful eyes of two Cadet Corporals.

SSP Prof Nandadasa Kodagoda, SSP P V W de Silva and a few other senior officers from Police HQ often attended as judges for different categories in the annual camp competitions, such as first aid, general knowledge, squad drill and physical training. Both these senior officers would discharge their duties to the rule and spirit.

All first-aid requirements were provided by the college St John’s Ambulance Brigade for all college special events, such as big matches and sports meets. This unit was led by 1979 Corporal Devapriya Perera (IT Professional – London) and most of the first-aiders were Police Cadets. They volunteered their services to the General Hospital Accident Ward and the Sri Pada pilgrims. It was pleasing to see Cadets controlling traffic duties in front of the college, at the Maradana – Borella main road, every morning, from 7.00 am to 7.25 am and helping with traffic duties and car park duties during the college sports meet and other functions.

Police Cadets CR Senanayake (Automobile Engineer-Brisbane), Ravi Mahendra (IT professional), and the late Dharmapriya Silva, established a swimming club that held its training at Otters Swimming Club. The School Bus Travelers Society, organized by the Police Cadets, issued bus seasons tickets for students with the help of CTB officials.

Back then when a teacher had not reported to a class, senior Police Cadets would step in and take turns to teach these classes. Deepal Sooriyaarchchi (Former MD of Aviva, Management Consultant) and Sarath Katangoda (Management Consultant – UK) were the most popular student masters in that era with their popular stories and innovative methods of teaching. This increased the popularity of police cadets among the other students. The way cadets conducted themselves had a very high impact on fellow Anandians, and the number of students attending practices rose rapidly.

On several occasions, Anula Vidyalaya Police Cadets called our Cadets to assist with their training in preparation for their Annual Camps. Having borrowed bus season tickets from students coming to College, via Nugegoda, our senior cadets were looking forward to visiting Anula to train them during school hours. This friendly culture blossoms during camps as well as outside the two schools. We still continue our friendships with Kamal Hathamuney (who joined the Army and retired with the rank of Major, residing in Sweden), Nirmala Perera, Malraji Meepegama (married to Maj Gen Sunil Wanniarachchi), Rosy Ranasekera (married to former Ananda Cadet Band leader Maj Gen Dhananjith Karunaratne) Dilani Balasuriya, (former IGP late Mahinda Balasuriya’s sister – married to Dr Priyanga de Zoysa). Interestingly our Cadet Lanka Herath continued this relationship and found his lifetime partner Ganga Thilakaratne from the Anula Vidyalaya Platoon. A famous school from Kelaniya, St Paul’s Balika Vidyalaya, too, started Police Cadeting in 1980. The writer being 1981 Ananda Sgt found his partner from St Paul’s Balika Cadet Sgt of the same year, Rasadari Jayamaha. Former Dean of the faculty of Law, University of Colombo Prof Indira Nanayakkara and Shiromi Perera (Melbourne) were the Corporals of the same platoon.

In 1972, the College platoon, led by Sgt Ranjith Wijesundara, became the Island’s best platoon. On the 23rd of July, 1983, the Sri Lankan Army’s routine patrol was assigned from Madagal to Gurunagar with the call sign of Four Four Bravo, commanded by 2/Lt A.P.N.C de Waas Gunwardane with 15 soldiers attached to Charlie company of SLLI were ambushed at Thirunelveli in Jaffna. 2/Lt Waas Gunawrdane and 12 soldiers made the supreme sacrifice. Adjutant and Intelligence Officer of SLLI Capt Ranjith Wijesundara was assigned the task of identifying the fallen heroes. Lt Wass Gunawardane was a Cadet of the 1977 platoon. Ranjith Wijesundra is now retired with the rank of Colonel.

In 1975 the College platoon, led by Sgt M A K E Manthriratne, also became the country’s best platoon and he was selected by the National Youth Council to represent the Sri Lanka Police Cadet Corps to travel to Canada under the Youth Exchange Programme between Sri Lanka and Canada. Manthriratne later joined the SL Navy and retired with the rank of Commander. Presently, as the President of Past Cadets, together with the ever-reliable 1982 Sgt V S Makolage carrying out various welfare projects under the banner of the Past Police Cadet Wing of Ananda.

Ananda held an unbroken record of winning nine out of 10 Trophies in 1978, under the great leadership of Sergeant Kithsiri Aponso who undoubtedly took Ananda Police Cadets to greater heights, was a leader with great charisma, integrity and leadership qualities. He became the Deputy Head Prefect and joined the STF. He later moved to the Police dept and is presently appointed as the DIG In Charge of the Badulla region.

The highest rank Cadet could achieve is Sgt Major. There were three Sgt Majors who brought honour and recognition to Ananda, namely Piyal Jayatilake in 1977, Jagathpriya Karunaratne in 1978 and ‘79, and Kithsiri Aponso in 1980. Chinthaka Gunaratne, a Cadet of 1981, also became the athletic Captain in 1983 (presently SSP In Charge of Highways) brought great honour and recognition as he became the Director in Charge of the Sri Lanka Police Cadet Corps.

College Athletic Captain of 1977, Ranasinghe Dharmadasa (Snr Manager BOI), 1978 JPPP Silva (Consultant-USA), 1980 Damitha Vitharana, (joined Sri Lanka Navy and retired as Lt. Commander and was the Director at Lankem Ceylon PLC before migrating to the UK), 1981 Jagath Palihakkara, (joined Sri Lanka Police as a SI in 1982 and at presently acting Senior DIG Western Region). DIG S M Y Senviratne another past Cadet joined the Police and is presently DIG in Charge of the Ampara Region. They also brought pride and joy to their alma mater during their time in their respective platoons and in their subsequent endeavours.

Two Sgts who led the Island’s best Platoons in 1983 Priyantha Ratnayake (Planter) and Pasindu Hearath of 2016 (Undergraduate of Kyoto University, Japan) became Head Prefects and Pasindu was awarded the Fritz Kunz Memorial Trophy for the Most Outstanding Student of 2017. The 4th of July 2017 was a great day for Ananda, as well as for the Police Cadets. 1980 Cadet Sgt who led the Island’s Best Platoon became Commander of the Army. It was a great honour for Cadets. Past Cadets organized a felicitation for Gen Mahesh Senanayake to recognise his prestigious appointment.

With profound gratitude, we remember past Cadets Rear Admiral Noel Kalubowila (a highly rated naval officer decorated with the highest gallantry medals especially having led the “Suicide Express” in 1990 evacuating troops from Jaffna Fort, Major General Lakshan Fernando, Major General Ajith Pallewela, Brig Mahinda Jayasinghe, Maj Aruna Vithanage, Maj Sampath Karuanthilake, Major SP Rodrigo, Lt Bandual Withanachchi, Director Prisons TI Uduwera, SSP Deepthi Hettiarchchi of STF (Zonal Commander Jaffna Mannar, Killinochchi and Mullaithivu), SSP Amal Edirimanne (In Charge of Colombo North) were Cadets who joined the forces, Police and Prison departments, respectively.

Chairman of University Grant Commission Senior Prof Sampath Amaratunge, one of the brilliant academics and a past Cadet, always believed and mentioned that “I am where I am because of my alma mater, and shall forever grateful to my journey”. Other note-worthy past Cadets are Harbor Master Capt Nirmal Silva, Prof Rohan Gunaratna (a political analyst specializing in international terrorism) present President of Ananda OBA, Bimal Wijesinghe who excelled in athletics during annual camps.

When this writer contacted one of our Masters-In-Charge, Mr W Weerasekera, he recalled those golden days. “As a pilot school where Police Cadet platoons were formed, Ananda College played its role in achieving the aims of cadetting as envisaged in the curriculum. It gives me great satisfaction to note the leadership and achievements of the Cadets, their success in later life with the highest contribution to the society at large”

Thanks for the untiring efforts of Hiranya Hewanayake (Senior Manager – Singer Sri Lanka) and Wing Commander Pradeep Kannangara Retd (Former Officer Commanding of the Special Air Borne Unit of Sri Lanka Air Force – Director – General Manager Abans Securitas), all past Cadets who reside all over the world are now well connected, via social media.We cherish the remarkable legacy of Ananda Police Cadetting.