Opinion

Mangala’s Aragalaya that never was, and must be

By Krishantha Prasad Cooray

In many ways, the economic collapse of Sri Lanka became a near certainty in the weeks after Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected President. In hindsight, it is clear to all that his government’s number one priority was consolidating their power and punishing those it saw as its enemies. Their next priority was enriching themselves. To the extent that they had anything resembling a policy focus, every major initiative taken by the Rajapaksas only served to further sabotage and doom our economy. But there was a darker, even more bitter and consequential turning point in our nation’s story than the election of November 2019. It was the loss our country suffered on 24 August 2021, with the demise of Mangala Samaraweera.

I say this not only because he was one of my closest friends – a man I deeply admired and trusted implicitly. He too had implicit faith in me and never doubted me. During the years in which we both served in the Yahapalanya government, Mangala and I would meet almost daily, whether at our homes or offices. It is safe to say that neither of us ever took a decision of any consequence without consulting the other. Despite the intimacy of our friendship, we did not blindly agree with or followed each other.

In fact, Mangala and I fought so frequently and bitterly that on my birthday last year, a highlight of the touching open letter he wrote to me was an acknowledgement that he has never fought with anyone as much as he has fought with me. We had plenty of areas of disagreement. He was an extremely loyal friend, and with this loyalty came the clearest proof that he was not infallible. Like many of us, Mangala sometimes trusted the wrong people, who would take advantage of his friendship.

While he could be misled, he was not easy to mislead. For example, Mangala was never one of those politicians who would blindly read out a script handed to him by third parties with vested interests. He welcomed input from his extremely talented and capable team. However, he was always the final arbiter of the words he would take to the nation. He excelled at communicating complex concepts in simple words, a far cry from leaders who drown us in a word salad of complex words to get across even the simplest message.

But whatever our disagreements, of one thing I am certain. If Mangala was alive, no matter how far our country fell, we would not feel so helpless, and devoid of alternatives to the status quo. While many of us could see early on that the government was doomed to fail, Mangala Samaraweera, as he had many times before in his career, saw something that others could not. As the finance minister mostly responsible for repairing the damage done to the Lankan economy in the previous decade of Rajapaksa rule, Mangala saw that the failure that was coming would be unlike any other before it. He realised that this time, failure could be so catastrophic that there may not even be an economy left to repair.

Spurred into action like he had never been before, Mangala was one of the single most important figures in the attempts in early 2020 to build a grand alliance among the opposition parties, to pose a united front against the Rajapaksas at the impending parliamentary elections. As a senior UNP MP, he worked tirelessly for months to bring as many parties as possible into the fold. The alliance that resulted under the blessing of the UNP was the Samagi Jana Balawegaya, or “United People’s Power”.

As one of the chief architects of the new alliance, it was Mangala’s vision that the party would encompass Sri Lankans of all races, religions and creeds, to pose a united front against the jingoistic, Sinhala Buddhist dominated, and backward policies that the Rajapaksas stood for. Even after his party, the UNP, dropped out of the alliance a few weeks before nominations were due in March 2020, Mangala stood fast, and was one of 52 UNP MPs to defy his party and forge ahead with the new alliance.

Being one of the most senior MPs from the Matara District, Mangala accepted the SJB’s nomination as District Leader in Matara. As one of the foremost political strategists of our time, he had to work around the clock with his colleagues to forge a fresh electoral message to take to the people at the parliamentary elections, to give them a credible alternate vision to the political views of the Rajapaksas.

Mangala was politically seasoned and rational enough to realise that the SJB could not win that election, but he wanted to directly appeal to as many of the 5.5 million Sri Lankans who had voted for Sajith Premadasa as possible. He wanted to give them a reason to come out to the polls, and to convert their support into a formidable political opposition that could stand together with other opposition parties. Mangala had a vision of a true ‘Joint Opposition’, one that could prevent the worst excesses of the Rajapaksas and present an alternate path to right the ship of state no sooner the country saw through the smoke and mirrors of the Gotabaya Rajapaksa propaganda machine.

His dream was not to be. He soon became convinced that the party he helped form was not going to provide a liberal alternative to the communal, traditional politics of the Rajapaksas that he had hoped for. Instead, several decisions he failed to prevent led Mangala to fear that voters would see the SJB pitch effectively as “Rajapaksa-lite”,

one where the influence of liberals such as himself, or minority party representatives would serve as an inclusive or progressive veneer on what would otherwise essentially be a Rajapaksa platform that catered to a single community above others and left progressive and egalitarian voters with nowhere to turn.

Mangala shared his fears with like-minded MPs, all of whom reminded him of a terrible truth: nominations had already been filed – their choices were to stay the course or to do the unthinkable and quit the race.

Mangala was deeply anguished by his predicament. He had won election from Matara for nearly 30 years, his entire adult life. He had contested from both the SLFP and the UNP, each time believing deeply and passionately in the party, the platform and the leaders he was asking the people of Matara to bring to power. But now, at the very last minute, he had to choose between trying to deceive his people, to convince them of something he no longer believed in his heart was true, or to give up his precious seat, leave parliamentary politics and find another way to help stave off disaster.

Mangala had no good choices. By June 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic had paralyzed the tourism industry. Meanwhile, the government remained hell bent on its pigheaded strategy to wreck the agriculture industry and accelerate the evaporation of our foreign reserves. As a former Finance Minister, and a leader who frequently saw what others could not, Mangala knew that time was running out.

Rightly or wrongly, he also felt that his party’s platform would not inspire voters to come to the polls as many would find its positions indistinguishable from those of the Rajapaksas or other parties. He concluded that the solution to save our country from the Rajapaksas would not come from Parliament, and so, he did the unthinkable.

On June 9, he appealed to the people of Matara not to vote for him, announcing that he did not wish to return to Parliament, and would instead do politics outside of Parliament. On that day, Mangala warned that Gotabaya Rajapaksa was meticulously dividing and isolating Sri Lankans and militarising the state, and that “the Opposition does not seem to have a clear understanding of what its role and duty should be at a time when the nation is faced with such grave challenges.”

Cynics have often dismissed Mangala as a coward who backed away from the election as he feared he would lose his seat. As someone who knew Mangala inside out, I can say with certainty that fear is a word Mangala simply did not understand. As a founder of the SJB, he could have easily sought and secured a spot on the national list and avoided contesting entirely. He never did. And in the two months between his handing in nominations and deciding to quit the race, nothing had changed that would have weakened his personal prospects. By this time, Mangala had matured beyond opportunistic politics towards principled politics. He was not a politician to whom capturing power came above all else.

With the country largely homebound and focused on the electioneering of the major parties, Mangala faded from the spotlight, and few understood the gravity of his decision until the election itself. As Mangala predicted, over a million voters who had voted for the UNP in 2019, disenchanted with that party and not seeing a viable alternative in the SJB, chose to stay at home. The boycott by these voters handed a two-thirds majority of Parliament to the Rajapaksas on a silver platter, leading in turn to the 20th Amendment and the unchecked excess and abuse that soon emptied our treasury and brought the country to its knees.

The writing on the wall was clear to Mangala well before the polls opened. A few days before the election, on August 2, he penned an article explaining what he saw as missing from the political spectrum that voters were to be presented with at the 2020 parliamentary elections. He set out the case for a “radical centre” on the political spectrum, for a movement whose founding principles and guiding light resembled those of our Constitution, and indeed, of the Buddhist philosophy embodied by Mangala himself – equality, egalitarianism and compassion. He spoke of a “common humanity, going beyond the boundaries of race, creed and caste.” Rejecting communalism in all its forms, he imagined a political movement that could directly confront the “thinly veiled racism and overzealous chauvinism” that pass for patriotism in Sri Lanka, a definition that he saw as “the main cause of our downhill journey since independence.”

Mangala called for a movement that would reimagine patriotism, to redefine it “to reflect the goals and aspirations of a modern Sri Lanka, rejecting the feudal and tribal attitudes and ‘big frog in a small well’ mindset of the Post-’56 era”. He imagined a party that could inspire Sri Lankans to understand, appreciate, respect and protect the very concept of democracy, and understand that fundamental rights were theirs to defend.

He devoted the rest of his article to setting out a policy agenda that resembles those of every advanced and prosperous country on the planet, with clearly articulated views that were both inspiring, and violently opposed to the Rajapaksa perspective on every issue from human rights, judicial independence, state sector reform, fiscal policy, combating narcotics, a robust safety net, advanced health care, education and the rights of women, children, the LGBTQ and animals. This article felt more inspiring and sincere than any manifesto produced by any party at the election that was just days away.

Having read his vision, I could not help but wonder what would have happened had this intelligent, courageous and forward-looking vision been put to the voters in August 2020. Would at least some of the 1.1 million 2019 voters who boycotted the election have been inspired to show up at the polls? At least enough of them to deny the Rajapaksas a two-thirds majority?

Mangala intended to inspire these disenchanted voters, unite them across lines that traditionally Opposition outside of Parliament. Having lived through the horrors that accompanied the armed insurrections of the JVP in the late 1980s, Mangala knew that when people began to starve, as was seeming inevitable, it would be up to the youth of the country to come together across ethnic and gender lines and to peacefully oppose the government and chart a course for the future.

Mangala spent the next year, through the lockdowns and adversity of the pandemic, putting together his “Radical Centre” movement, which he launched at Darley Road on 25 July 2021, the 38th anniversary of the 1983 Black July riots. By this time, the Opposition had rallied in unison behind the slogan “Sir Fail”, rightly chastising Gotabaya Rajapaksa for his abysmal failure to govern. But in launching his “Radical Centre” Mangala went a step further.

He resisted the convenient slogan and inspired people to look deeper and more introspectively. “Sri Lanka has fallen into this state today because of decades of politics through the sale of false patriotism, the voters who were continuously deceived by these so-called patriots,” he said.

He did not even spare himself. “In fact, everyone else involved in governance, including myself, is to some extent responsible for the current situation,” Mangala said. He stressed that it was not just one man, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who had failed, but an entire system of political thinking.

“But it is not President Gotabaya Rajapaksa who has really failed today. It is the religious, majoritarian and outdated socialist ideologies he represents that have failed. Today, it is the Government that promised a solitary Sinhala Government that has failed. Who has failed today is the present Opposition which has gone beyond Rajapaksa in proposing an ideology containing racism and majoritarianism as a solution.”

He built the “Radical Centre” and its headquarters, “Freedom House”, to be focused on the energy, aptitude and aspirations of our youth, with a special focus on professionals who would typically shy away from politics. He planned to present the people with an alternative, educating them on the dangers of the government’s policies, and on how they could be successfully and peacefully opposed. He planned to bring the government to its knees in a way that he felt that the political opposition in Parliament simply lacked the vision, motivation or appetite to do.

His message to the youth was that we, the older generation had failed them, and that it was time that they took the future of the country they would inherit into their own hands. He planted the seeds of what would become the Aragalaya, by inspiring young Sri Lankans to unite and stand up for their rights and their future.

Despite being politically opposed to the Rajapaksas and the Podujana Peramuna, Mangala opposed them responsibly, averse to scoring cheap shots for petty political gain. Just as he was dismissive of the “Sir Fail” simplification of our country’s plight, he had quietly lent his own personal connections to the government earlier that year to try and secure additional vaccine doses and other aid for the country.

Even though he succeeded, he never sought credit, and didn’t try to get his picture in the newspapers receiving stocks of vaccine doses or supplies at the airport or distributing them on camera. He just got the job done. Mangala had risen above politics and fully embraced statesmanship. He was not a party leader. He was a real leader.

In Mangala’s final days, as his Covid-19 treatment grew more intense and his family desperately sought hard to find medication, one politician who helped secure an injection for Mangala actually took to social media to boast of his own charity and generosity. Contrast that to Mangala, who silently mobilised entire countries to procure supplies for millions, and never said a word or sought a lick of praise. That is the difference between Mangala Samaraweera and the choices we are left with today.

In addition, for months prior to launching his movement, Mangala had been writing letters and reports privately and in detail for the consumption of the Rajapaksa government, trying to explain the gravity of the economic devastation that he warned was only months away, virtually pleading with them to change course, to stop bleeding our foreign reserves dry and setting out for them a policy path that could have prevented the worst of the suffering we are enduring today. He never spoke of his fears publicly, conscious of his stature as a former finance minister and fearful of contributing towards the flight of investors or a credit downgrade. He refused to exacerbate the suffering of ordinary Sri Lankans for personal political expediency.

Perhaps, as the situation deteriorated, he would have become more vocal, and tried to use his burgeoning youth movement to advocate for specific policy reversals before the coffers ran dry and we were forced into default. Alas, we will never know. He succeeded in getting the youth to pay attention, but sadly, he was not there to help shape what was next to come.

It was just days after Mangala launched the “Radical Centre” in July 2021, that he contracted COVID-19. After several weeks of fighting fiercely against the disease, on Tuesday, August 24, 2021, Mangala succumbed, and Sri Lanka lost one of its titans of democracy, its paragons of statesmanship. Just 30 days after beginning the most courageous, ambitious, and essential phase of his political journey, suddenly, Mangala was no more.

Mangala’s demise left a gaping hole on Sri Lanka’s political spectrum. He had planned to unite the youth across political party lines and coordinate the peaceful fight against the Rajapaksas with one voice. But with his demise, no leader had the courage or vision to step in to fill that void. No leader had the credibility to unite the youth in an egalitarian, liberal and secular front. No leader had the capacity or team capable enough to bring such an ambitious vision to fruition.

As the cost of living skyrocketed and the country teetered on bankruptcy, the youth took matters into their own hands, launching a leaderless Aragalaya sparked by the unbearable cost of feeding their families and the realization that Rajapaksa policies would lead to the next generations of Sri Lankans being significantly poorer, hungrier, unhealthier and worse off.

In the absence of leadership, the Aragalaya united around the lowest common denominator, a single call to action: “Gota Go Home.” Their bases became “Gota Go” gamas, or villages.

Alas, even as their numbers burgeoned, and tens of thousands more Sri Lankans rallied around the obvious truth that Gotabaya Rajapaksa had to go home, something happened in Sri Lanka that has never ever happened in any country that has undergone a revolution of this nature. What happened in Sri Lanka would never, ever, have happened if Mangala Samaraweera was alive.

While the country was clear that Gotabaya Rajapaksa had failed, there was not a credible leader in sight with the vision, courage, and political acumen to come forward with an alternative to Rajapaksa policies instead of a substitute, or Rajapaksa-lite. The opposition parties were highly effective at pointing out what the Rajapaksas did wrong. But barring a few outstandingly prescient and learned MPs who could speak in technical terms of potential alternate policies to the Rajapaksas, no leader came forward to inspire the country with an alternative vision.

Devoid of any political leadership, most of the contributors to the Aragalaya movement, especially those who were students of history, were fearful of electing leaders among themselves or making any political claims. They had clearly hoped that if they did the hard work of dislodging and breaking the most powerful, authoritarian government that had ever ruled Sri Lanka, that there would be a leader to come forward and provide an alternate path. Sadly, they could not have been more wrong.

In the absence of someone like Mangala to put forward an inspiring, thoughtful and credible alternative, much of the Aragalaya narrative was hijacked by the extreme left, those with anarchist agendas, who would burn the houses of MPs, resort to thuggery, and sought to tear down our democracy in its entirety. These people took the spotlight, torching homes and taking lives, scaring the people that what was to come was no different to Rajapaksa brutality.

As it happened, there was no one to protect the vast majority of innocent youth who devoted their sweat, blood and tears to give their children a better future. They were abandoned and on their own.

Mangala saw, over a year before the Aragalaya was born, that it would be the youth of Sri Lanka, united along all demographic lines, who would pose the only credible threat to the government. He knew they would come together as the cost of living reached for the stars. And despite knowing that this inevitability would have benefited him politically, he fought until he could no longer draw breath to prevent that outcome by privately seeking to convince the government to avoid disaster. In his absence, we are left with so-called leaders who wait with bated breath for the plane to crash, foolish enough to imagine that they can then become its next pilot.

Mangala, on the other hand, was sharper, more principled, and pragmatic. He saw, over a year before the Aragalaya was born, that such a movement could – and must – reclaim the concept of “patriotism” from the nationalists and the xenophobes. Having been called a “traitor” for years for standing by his principles, he stood fast, knowing that history would be on his side. He was right. When I saw young Sri Lankan boys and girls, Sinhalese and Tamils, Buddhists, Christians and Muslims, wrapped in Sri Lankan flags singing the national anthem as they redefined patriotism in protest against the Rajapaksas, my heart skipped a beat, my mind went straight to Mangala, and I choked back tears. If Mangala were alive to see it, he would have wept openly with pride.

Today, Gotabaya Rajapaksa is gone, but his family and political party still dominate the corridors of power. Today, the genuine youth movement Mangala saw coming has materialized, been splintered, and shattered by isolation, incarceration and disillusionment. And today, we can finally see what Mangala could see as far back as August 2020, before the SLPP ever took Parliament.

Mangala knew that the SLPP would fail. He knew that in poverty, Sri Lankans would find unity, and that no leader in Parliament would be ready with an alternative to the Rajapaksas coupled with the courage to act. He knew the risks of a poverty-driven youth rebellion, having lived through one himself, and he understood that it was essential to build a clear message of hope and an alternative to just attacking what was failing. He knew that by the time the government failed, if not sooner, the political centre had to be ready with a plan to succeed.

In remembering Mangala, we must remember his most important lesson. He warned that defeating a single President, a single family, a single party, or winning a single election, would not be enough. Gotabaya Rajapaksa left office, but the ideology he stood for, that brought us to ruin, is still very much with us. If Sri Lanka is to have any hope, this ideology must be defeated and stamped out once and for all. In the same vein, even though Mangala has left this earth, his radical centrist ideology still exists, if not in Parliament, if not in the media, at least in the hearts of the Sri Lankan youth and clear-minded citizens. And if our country is to truly ever thrive again, Mangala’s ideology must be protected, it must blossom, it must become our national ideology. It must become our new patriotism. And the true patriots of Sri Lanka must remain united and make this vision a reality. This is the only way forward for our country.

Opinion

Child food poverty: A prowling menace

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin),

FRCP(Lon), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow,

Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health

In an age of unprecedented global development, technological advancements, universal connectivity, and improvements in living standards in many areas of the world, it is a very dark irony that child food poverty remains a pressing issue. UNICEF defines child food poverty as children’s inability to access and consume a nutritious and diverse diet in early childhood. Despite the planet Earth’s undisputed capacity to produce enough food to nourish everyone, millions of children still go hungry each day. We desperately need to explore the multifaceted deleterious effects of child food poverty, on physical health, cognitive development, emotional well-being, and societal impacts and then try to formulate a road map to alleviate its deleterious effects.

Every day, right across the world, millions of parents and families are struggling to provide nutritious and diverse foods that young children desperately need to reach their full potential. Growing inequities, conflict, and climate crises, combined with rising food prices, the overabundance of unhealthy foods, harmful food marketing strategies and poor child-feeding practices, are condemning millions of children to child food poverty.

In a communique dated 06th June 2024, UNICEF reports that globally, 1 in 4 children; approximately 181 million under the age of five, live in severe child food poverty, defined as consuming at most, two of eight food groups in early childhood. These children are up to 50 per cent more likely to suffer from life-threatening malnutrition. Child Food Poverty: Nutrition Deprivation in Early Childhood – the third issue of UNICEF’s flagship Child Nutrition Report – highlights that millions of young children are unable to access and consume the nutritious and diverse diets that are essential for their growth and development in early childhood and beyond.

It is highlighted in the report that four out of five children experiencing severe child food poverty are fed only breastmilk or just some other milk and/or a starchy staple, such as maize, rice or wheat. Less than 10 per cent of these children are fed fruits and vegetables and less than 5 per cent are fed nutrient-dense foods such as eggs, fish, poultry, or meat. These are horrendous statistics that should pull at the heartstrings of the discerning populace of this world.

The report also identifies the drivers of child food poverty. Strikingly, though 46 per cent of all cases of severe child food poverty are among poor households where income poverty is likely to be a major driver, 54 per cent live in relatively wealthier households, among whom poor food environments and feeding practices are the main drivers of food poverty in early childhood.

One of the most immediate and visible effects of child food poverty is its detrimental impact on physical health. Malnutrition, which can result from both insufficient calorie intake and lack of essential nutrients, is a prevalent consequence. Chronic undernourishment during formative years leads to stunted growth, weakened immune systems, and increased susceptibility to infections and diseases. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition are more likely to suffer from conditions such as anaemia, rickets, and developmental delays.

Moreover, the lack of proper nutrition can have long-term health consequences. Malnourished children are at a higher risk of developing chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity later in life. The paradox of child food poverty is that it can lead to both undernutrition and overnutrition, with children in food-insecure households often consuming calorie-dense but nutrient-poor foods due to economic constraints. This dietary pattern increases the risk of obesity, creating a vicious cycle of poor health outcomes.

The impacts of child food poverty extend beyond physical health, severely affecting cognitive development and educational attainment. Adequate nutrition is crucial for brain development, particularly in the early years of life. Malnutrition can impair cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and problem-solving skills. Studies have consistently shown that malnourished children perform worse academically compared to their well-nourished peers. Inadequate nutrition during early childhood can lead to reduced school readiness and lower IQ scores. These children often struggle to concentrate in school, miss more days due to illness, and have lower overall academic performance. This educational disadvantage perpetuates the cycle of poverty, as lower educational attainment reduces future employment opportunities and earning potential.

The emotional and psychological effects of child food poverty are profound and are often overlooked. Food insecurity creates a constant state of stress and anxiety for both children and their families. The uncertainty of not knowing when or where the next meal will come from can lead to feelings of helplessness and despair. Children in food-insecure households are more likely to experience behavioural problems, including hyperactivity, aggression, and withdrawal. The stigma associated with poverty and hunger can further exacerbate these emotional challenges. Children who experience food poverty may feel shame and embarrassment, leading to social isolation and reduced self-esteem. This psychological toll can have lasting effects, contributing to mental health issues such as depression and anxiety in adolescence and adulthood.

Child food poverty also perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality. Children who grow up in food-insecure households are more likely to remain in poverty as adults, continuing the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage. This cycle of poverty exacerbates social disparities, contributing to increased crime rates, reduced social cohesion, and greater reliance on social welfare programmes. The repercussions of child food poverty ripple through society, creating economic and social challenges that affect everyone. The healthcare costs associated with treating malnutrition-related illnesses and chronic diseases are substantial. Additionally, the educational deficits linked to child food poverty result in a less skilled workforce, which hampers economic growth and productivity.

Addressing child food poverty requires a multi-faceted approach that tackles both immediate needs and underlying causes. Policy interventions are crucial in ensuring that all children have access to adequate nutrition. This can include expanding social safety nets, such as food assistance programmes and school meal initiatives, as well as targeted manoeuvres to reach more vulnerable families. Ensuring that these programmes are adequately funded and effectively implemented is essential for their success.

In addition to direct food assistance, broader economic and social policies are needed to address the root causes of poverty. This includes efforts to increase household incomes through living wage policies, job training programs, and economic development initiatives. Supporting families with affordable childcare, healthcare, and housing can also alleviate some of the financial pressures that contribute to food insecurity.

Community-based initiatives play a vital role in combating child food poverty. Local food banks, community gardens, and nutrition education programmes can help provide immediate relief and promote long-term food security. Collaborative efforts between government, non-profits, and the private sector are necessary to create sustainable solutions.

Child food poverty is a profound and inescapable issue with far-reaching consequences. Its deleterious effects on physical health, cognitive development, emotional well-being, and societal stability underscore the urgent need for comprehensive action. As we strive for a more equitable and just world, addressing child food poverty must be a priority. By ensuring that all children have access to adequate nutrition, we can lay the foundation for a healthier, more prosperous future for individuals and society as a whole. The fight against child food poverty is not just a moral imperative but an investment in our collective future. Healthy, well-nourished children are more likely to grow into productive, contributing members of society. The benefits of addressing this issue extend beyond individual well-being, enhancing economic stability and social harmony. It is incumbent upon us all to recognize and act upon the understanding that every child deserves the right to adequate nutrition and the opportunity to thrive.

Despite all of these existent challenges, it is very definitely possible to end child food poverty. The world needs targeted interventions to transform food, health, and social protection systems, and also take steps to strengthen data systems to track progress in reducing child food poverty. All these manoeuvres must comprise a concerted effort towards making nutritious and diverse diets accessible and affordable to all. We need to call for child food poverty reduction to be recognized as a metric of success towards achieving global and national nutrition and development goals.

Material from UNICEF reports and AI assistance are acknowledged.

Opinion

Do opinion polls matter?

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

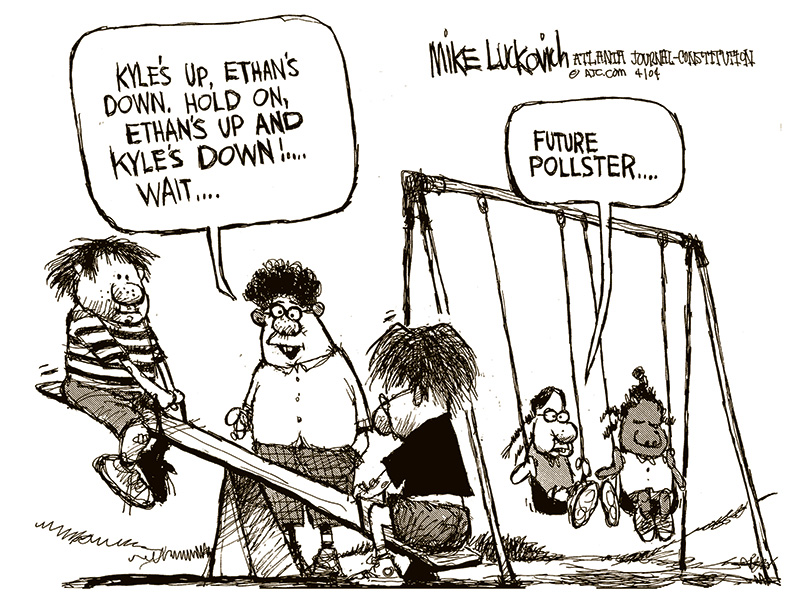

The colossal failure of not a single opinion poll predicting accurately the result of the Indian parliamentary election, the greatest exercise in democracy in the world, raises the question whether the importance of opinion polls is vastly exaggerated. During elections two types of opinion polls are conducted; one based on intentions to vote, published during or before the campaign, often being not very accurate as these are subject to many variables but exit polls, done after the voting where a sample tally of how the voters actually voted, are mostly accurate. However, of the 15 exit polls published soon after all the votes were cast in the massive Indian election, 13 vastly overpredicted the number of seats Modi’s BJP led coalition NDA would obtain, some giving a figure as high as 400, the number Modi claimed he is aiming for. The other two polls grossly underestimated predicting a hung parliament. The actual result is that NDA passed the threshold of 272 comfortably, there being no landslide. BJP by itself was not able to cross the threshold, a significant setback for an overconfident Mody! Whether this would result in less excesses on the part of Modi, like Muslim-bashing, remains to be seen. Anyway, the statement issued by BJP that they would be investigating the reasons for failure rather than blaming the process speaks very highly of the maturity of the democratic process in India.

I was intrigued by this failure of opinion polls as this differs dramatically from opinion polls in the UK. I never failed to watch ‘Election night specials’ on BBC; as the Big Ben strikes ‘ten’ (In the UK polls close at 10pm} the anchor comes out with “Exit polls predict that …” and the actual outcome is often almost as predicted. However, many a time opinion polls conducted during the campaign have got the predictions wrong. There are many explanations for this.

An opinion poll is defined as a research survey of public opinion from a particular sample, the origin of which can be traced back to the 1824 US presidential election, when two local newspapers in North Carolina and Delaware predicted the victory of Andrew Jackson but the sample was local. First national survey was done in 1916 by the magazine, Literary Digest, partly for circulation-raising, by mailing millions of postcards and counting the returns. Of course, this was not very scientific though it accurately predicted the election of Woodrow Wilson.

Since then, opinion polls have grown in extent and complexity with scientific methodology improving the outcome of predictions not only in elections but also in market research. As a result, some of these organisations have become big businesses. For instance, YouGov, an internet-based organisation co-founded by the Iraqi-born British politician Nadim Zahawi, based in London had a revenue of 258 million GBP in 2023.

In Sri Lanka, opinion polls seem to be conducted by only one organisation which, by itself, is a disadvantage, as pooled data from surveys conducted by many are more likely to reflect the true situation. Irrespective of the degree of accuracy, politicians seem to be dependent on the available data which lend explanations to the behaviour of some.

The Institute for Health Policy’s (IHP) Sri Lanka Opinion Tracker Survey has been tracking the voting intentions for the likely candidates for the Presidential election. At one stage the NPP/JVP leader AKD was getting a figure over 50%. This together with some degree of international acceptance made the JVP behave as if they are already in power, leading to some incidents where their true colour was showing.

The comments made by a prominent member of the JVP who claimed that the JVP killed only the riff-raff, raised many questions, in addition to being a total insult to many innocents killed by them including my uncle. Do they have the authority to do so? Do extra-judicial killings continue to be JVP policy? Do they consider anyone who disagrees with them riff-raff? Will they kill them simply because they do not comply like one of my admired teachers, Dr Gladys Jayawardena who was considered riff-raff because she, as the Chairman of the State Pharmaceutical Corporation, arranged to buy drugs cheaper from India? Is it not the height of hypocrisy that AKD is now boasting of his ties to India?

Another big-wig comes with the grand idea of devolving law and order to village level. As stated very strongly, in the editorial “Pledges and reality” (The Island, 20 May) is this what they intend to do: Have JVP kangaroo-courts!

Perhaps, as a result of these incidents AKD’s ratings has dropped to 39%, according to the IHP survey done in April, and Sajith Premadasa’s ratings have increased gradually to match that. Whilst they are level pegging Ranil is far behind at 13%. Is this the reason why Ranil is getting his acolytes to propagate the idea that the best for the country is to extend his tenure by a referendum? He forced the postponement of Local Governments elections by refusing to release funds but he cannot do so for the presidential election for constitutional reasons. He is now looking for loopholes. Has he considered the distinct possibility that the referendum to extend the life of the presidency and the parliament if lost, would double the expenditure?

Unfortunately, this has been an exercise in futility and it would not be surprising if the next survey shows Ranil’s chances dropping even further! Perhaps, the best option available to Ranil is to retire gracefully, taking credit for steadying the economy and saving the country from an anarchic invasion of the parliament, rather than to leave politics in disgrace by coming third in the presidential election. Unless, of course, he is convinced that opinion polls do not matter and what matters is the ballots in the box!

Opinion

Thoughtfulness or mindfulness?

By Prof. Kirthi Tennakone

ktenna@yahoo.co.uk

Thoughtfulness is the quality of being conscious of issues that arise and considering action while seeking explanations. It facilitates finding solutions to problems and judging experiences.

Almost all human accomplishments are consequences of thoughtfulness.

Can you perform day-to-day work efficiently and effectively without being thoughtful? Obviously, no. Are there any major advancements attained without thought and contemplation? Not a single example!

Science and technology, art, music and literary compositions and religion stand conspicuously as products of thought.

Thought could have sinister motives and the only way to eliminate them is through thought itself. Thought could distinguish right from wrong.

Empathy, love, amusement, and expression of sorrow are reflections of thought.

Thought relieves worries by understanding or taking decisive action.

Despite the universal virtue of thoughtfulness, some advocate an idea termed mindfulness, claiming the benefits of nurturing this quality to shape mental wellbeing. The concept is defined as focusing attention to the present moment without judgment. A way of forgetting the worries and calming the mind – a form of meditation. A definition coined in the West to decouple the concept from religion. The attitude could have a temporary advantage as a method of softening negative feelings such as sorrow and anger. However, no man or woman can afford to be non-judgmental all the time. It is incompatible with indispensable thoughtfulness! What is the advantage of diverting attention to one thing without discernment during a few tens of minute’s meditation? The instructors of mindfulness meditation tell you to focus attention on trivial things. Whereas in thoughtfulness, you concentrate the mind on challenging issues. Sometimes arriving at groundbreaking scientific discoveries, solution of mathematical problems or the creation of masterpieces in engineering, art, or literature.

The concept of meditation and mindfulness originated in ancient India around 1000 BCE. Vedic ascetics believed the practice would lead to supernatural powers enabling disclosure of the truth. Failing to meet the said aspiration, notwithstanding so many stories in scripture, is discernable. Otherwise, the world would have been awakened to advancement by ancient Indians before the Greeks. The latter culture emphasized thoughtfulness!

In India, Buddha was the first to deviate from the Vedic philosophy. His teachers, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputra, were adherents of meditation. Unconvinced of their approach, Buddha concluded a thoughtful analysis of the actualities of life should be the path to realisation. However, in an environment dominated by Vedic tradition, meditation residually persisted when Buddha’s teachings transformed into a religion.

In the early 1970s, a few in the West picked up meditation and mindfulness. We Easterners, who criticize Western ideas all the time, got exalted after seeing something Eastern accepted in the Western circles. Thereafter, Easterners took up the subject more seriously, in the spirit of its definition in the West.

Today, mindfulness has become a marketable commodity – a thriving business spreading worldwide, fueled largely by advertising. There are practice centres, lessons onsite and online, and apps for purchase. Articles written by gurus of the field appear on the web.

What attracts people to mindfulness programmes? Many assume them being stressed and depressed needs to improve their mental capacity. In most instances, these are minor complaints and for understandable reasons, they do not seek mainstream medical interventions but go for exaggeratedly advertised alternatives. Mainstream medical treatments are based on rigorous science and spell out both the pros and cons of the procedure, avoiding overstatement. Whereas the alternative sector makes unsubstantiated claims about the efficacy and effectiveness of the treatment.

Advocates of mindfulness claim the benefits of their prescriptions have been proven scientifically. There are reports (mostly in open-access journals which charge a fee for publication) indicating that authors have found positive aspects of mindfulness or identified reasons correlating the efficacy of such activities. However, they rarely meet standards normally required for unequivocal acceptance. The gold standard of scientific scrutiny is the statistically significant reproducibility of claims.

If a mindfulness guru claims his prescription of meditation cures hypertension, he must record the blood pressure of participants before and after completion of the activity and show the blood pressure of a large percentage has stably dropped and repeat the experiment with different clients. He must also conduct sessions where he adopts another prescription (a placebo) under the same conditions and compares the results. This is not enough, he must request someone else to conduct sessions following his prescription, to rule out the influence of the personality of the instructor.

The laity unaware of the above rigid requirements, accede to purported claims of mindfulness proponents.

A few years ago, an article published and widely cited stated that the practice of mindfulness increases the gray matter density of the brain. A more recent study found there is no such correlation. Popular expositions on the subject do not refer to the latter report. Most mindfulness research published seems to have been conducted intending to prove the benefits of the practice. The hard science demands doing the opposite as well-experiments carried out intending to disprove the claims. You need to be skeptical until things are firmly established.

Despite many efforts diverted to disprove Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, no contradictions have been found in vain to date, strengthening the validity of the theory. Regarding mindfulness, as it stands, benefits can neither be proved nor disproved, to the gold standard of scientific scrutiny.

Some schools in foreign lands have accommodated mindfulness training programs hoping to develop the mental facility of students and Sri Lanka plans to follow. However, studies also reveal these exercises are ineffective or do more harm than good. Have we investigated this issue before imitation?

Should we force our children to focus attention on one single goal without judgment, even for a moment?

Why not allow young minds to roam wild in their deepest imagination and build castles in the air and encourage them to turn these fantasies into realities by nurturing their thoughtfulness?

Be more thoughtful than mindful?