Life style

The Secret to Saving Asian

Elephants ? Oranges

BY ZINARA RATNAYAKE

In Sri Lanka, human-elephant conflict has disrupted farmers for generations. In some cases, people are killed. Now, a local conservation organization is looking to citrus as a solution. Bees and fences can’t stop elephants from attacking villages—but orange trees miraculously can.

The November morning was blue-skied and bright. When Wije appeared behind the large orange tree shading his front yard, his eyes crinkled with a broad smile. He wore a rainbow-coloured sarong, a blue face mask, and a Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS) T-shirt. This is where he works as a fieldhouse manager. He plucked an orange from a tree to prepare juice. In his village, oranges aren’t just a fruit. They’re a solution to an age-old environmental problem: human-elephant conflict.

Like many villages in the countryside of Sri Lanka, Pussellayaya boasts postcard-worthy landscapes. Wije, short for Aluthgedara Wijerathne, is a 43-year-old native of Pussellayaya, which sits in the southern boundary of Wasgamuwa National Park, about 143 miles from the capital city Colombo in Sri Lanka.

When the charred evening clouds in November bring rain to the village, farmers start sowing the fields of paddy that disappear into a ridgeline of the Knuckles Mountain Range. In the coming months, farmers toil in the fields, but the surrounding wildlife doesn’t make their life easy.

“During the last decade, elephants killed four villagers,” says Wije in his native language Sinhala. “We get very scared at night. Elephants came to destroy our crops and houses. We didn’t have a choice but to retaliate. We lit firecrackers to scare them off, but they became more aggressive, so we fired gunshots into the air, and sometimes at elephants. We didn’t want to harm wild animals, but they were destroying everything we had.”

Growing up in the village, Wije remembers the sleepless nights he spent with his parents. They lit fires and slept on rickety treehouses in the open air in the rice fields, trying to scare off hungry elephants looking for ripe paddy—the only source of income Wije’s parents had.

Orange trees have helped protect Wije’s rice crops while helping him branch out into the world of citrus.

Wije’s story is not different from that of thousands of others living in rural Sri Lanka. The country’s rapidly growing human population and subsequent demand for land result in clearing of natural habitats, squeezing wild animals—like elephants—into smaller pockets of land

The Sri Lankan sub-species of the Asian elephant is already endangered—with as few as 2,500 elephants remaining in Sri Lanka today—but this forces them into shattered jungle habitats. Wild elephants rampage adjacent villages (their original habitat) looking for natural sources of food and water.

A 2010 report by Columbia University’s Earth Institute found that, historically, elephant deaths coincided with reduced rainfall in Sri Lanka’s eastern region. The climate crisis is set to change precipitation patterns in the country and increase the risk of drought. Sri Lanka, which ranked second in the 2019 global climate risk index, already experiences erratic weather patterns.

During Sri Lanka’s dry season, water bodies dry up. Trees wither. Water buffaloes resort to the last remaining mud puddles while searing hot weather cracks the arid soil. In this fetid heat, elephants frequently wander around looking for water, some of them migrating through human habitats where resources exist.

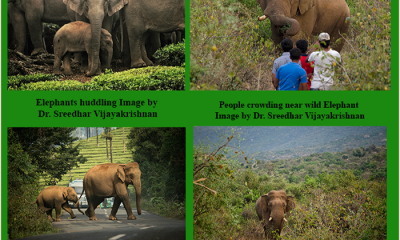

Every year in Sri Lanka, the elephants destroy $10 million worth of crops and property. For the last two years, elephants have killed more than 90 people a year in Sri Lanka. Fearful farmers fight back; in 2019, they killed a record 405 elephants. While human-elephant conflict is a threat to these jungle giants, it also puts impoverished farmers in a vulnerable situation.

“We need to help humans first. If we do that, we can save elephants.”

In the early 1990s, conservationists in Sri Lanka tried to solve the problem by installing electric fences around the villages. But elephants are smart creatures: They began using sticks or branches to break these wires. Busy farmers then have to spend time rebuilding the wires. Ravi Corea, founder of SLWCS, says that farmers who live hand to mouth don’t have the luxury of spending time on such repairs.

Corea understood the need for a long-term solution during his time near Wasgamuwa about three decades ago. After he launched SLWCS in 1995, Corea initiated the project Saving Elephants by Helping People (SEHP) in 1997 to research community-led responses. “I realized that we need to help humans first,” he says. “If we do that, we can save elephants.”

Around 2005, Corea got a surprising tip from the villagers. “Elephants are amazing creatures,” he says, laughing. “They like to remind us that they are the kings in the jungle.”

Elephants often display their power by uprooting trees—but there was one type they left alone: citrus.

So a year later, SLWCS conducted a series of feeding trials with six captive Asian elephants at Dehiwala Zoo, located in suburban Colombo. While elephants gulped down other things such as melons, bananas, paddy, and palm leaves, they tended to eschew oranges and lime fruits and leaves. Their study (which has not been peer-reviewed) concluded that Asian elephants in Sri Lanka have a natural aversion to citrus.

The researchers never found out why elephants didn’t like citrus—they suspect the compound called limonene might be behind it—but those results were promising enough to expand the solution. Corea had already tried other options in between—like beehive fences. They involve fencing the farmer’s crops with beehives. This invention has worked in parts of Africa, but Sri Lankan bees don’t sting as hard as the killer bees of Africa. Moreover, the bees would leave in the dry season in search of water.

By 2011, SLWCS moved forward on the potential citrus solution: It donated orange trees to 12 farmers in Radunna Wewa, another small hamlet in Wasgamuwa. After three years, as the orange plants grew, the farmers saw the difference the plants made. While elephants still stormed through the surrounding main roads, they would take a detour when they smelled citrus. The strong smell of orange now keeps the elephants out of the village, protecting crops and property.

Sixty-year-old Waththegedara Anulawathie is one of Radunna Wewa’s first orange growers. “Elephants don’t come now,” Anulawathie says, her wrinkled face lighting up. Her black and gray hair is loosely braided; her baby pink blouse bright against the backdrop of paddy fields nearby. “Some months, we lost most of our harvest,” she says, pointing to where elephants reduced a house to nothing. “Now we go to sleep at night,” she smiles.

Since their earliest program in Radunna Wewa almost 10 years ago, SLWCS has planted trees in more than 12 villages in the Wasgamuwa region, distributing 25,000 orange plants. Pussellayaya is one of their latest additions. Each of the village’s 300 houses has at least 10 orange trees. In the last five years, SLWCS has estimated that the Wasgamuwa region contributed only about two percent to national human-elephant conflict—including property and crop damage, human deaths, and elephant deaths—according to annual data the organization collects from the region’s Department of Wildlife Conservation.

“Now elephants don’t harm the poor farmers, and farmers don’t harm the elephants,” Corea says, “It’s a win-win for both parties.”

While oranges kept elephants away, their commercial value further incentivized farmers to cultivate the crop. Most traditional paddy farmers struggle to meet their needs, but oranges now provide them an additional income. Farmers grow Bibile sweets, a green orange from Bibile, Sri Lanka, which suits the climate. Anulawathie says a fully grown tree yields about 300 to 500 oranges, which she sells for 15 rupees (about $0.10) each.

However, soaring heat and extreme drought threaten these orchards. In Anulawathie’s garden, two young trees died in August, the driest month of the year. While SLWCS has already developed an irrigation system that brings in water from nearby canals, lakes, and springs, farmers are still struggling.

As more farmers grow Bibile sweets, Corea says they will help protect the natural water springs. Once the trees grow into large orchards, they’ll help shade the bare soil from the harsh sun. Birds, butterflies, and other insects come for orange flowers, too, increasing the area’s biodiversity. “Oranges are addressing the issues of the ecosystem shared by elephants, humans, and other wildlife,” Corea says.

SLWCS relies on volunteers and donations for its projects. While Corea has plans to expand this program, the conservation efforts would require more financial support and intervention from government authorities. Corea and his team had planned to begin feeding trials in Tanzania to African elephants, but the pandemic put that on pause. “We want to see if African elephants show a resistance to citrus as well.”

Now that elephants don’t come to raid their paddy, farmers in Pussellayaya can sleep peacefully. They can reap and sell their harvest in full. Wije, for instance, was able to buy a tuk tuk (auto rickshaw) with last year’s earnings. Wije walks me around the village and shows me a home. The garden is dotted with orange trees, planted only four years ago. In May, the family sold their first harvest.

We walk to the SLWCS field office, and Wije squeezes a few oranges for juice. It’s a great way to kill the scorching heat. Wije peels off the orange rind, but he has already learned that the outer skin is also useful. SLWCS is planning to make essential oil from orange peel, as well as introduce products with a longer shelf life: jam, bottled-juices, and cordials.

Wije believes these products can help bring more income to the villagers. “Until then, we are thankful that elephants don’t come here anymore. Our rice is safe. Our houses are safe. We are safe,” Wije says, smiling. “Elephants are safe, too.”

(BBC)

Life style

Camaraderie,reflection and achievements

Institute of Hospitality Sri Lanka

The 32nd Annual General Meeting (AGM) of the UK-based Institute of Hospitality’s Sri Lanka Chapter was held recently at the Ramada Hotel Colombo,.The event provided an evening of camaraderie , reflection of the past and present achievements,setting new benchmarks for the future

The 32nd Annual General Meeting (AGM) of the UK-based Institute of Hospitality’s Sri Lanka Chapter was held recently at the Ramada Hotel Colombo,.The event provided an evening of camaraderie , reflection of the past and present achievements,setting new benchmarks for the future

The AGM had the presence of two distinguished guests, the Chief Guest Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa, and the Guest of Honour British High Commissioner to Sri Lanka, Andrew Patrick. Their inspiring speeches were lauded by all hoteliers who were present at the occasion

A special thanks was extended to Robert Richardson, CEO of the Institute of Hospitality UK, along with his team, sponsors, committee members, and all attendees for making the event memorable.

Dr. Harsha Jayasingh, Past President of the Institute of Hospitality (UK) Sri Lanka Chapter, emphasised the Institute’s longstanding history and the strength of its Sri Lankan branch. “The Institute of Hospitality (IH) UK has a history of 86 years, and we are proud to be the Sri Lanka Branch. IH Sri Lanka is much stronger now with many members from all areas of the hospitality industry,” he stated.

Dr. Jayasingh highlighted the significant role of tourism in Sri Lanka’s economy,. He said tourism it is the third-largest source of revenue for the country. “Tourism accounts for about 13.3% of total foreign exchange earnings and employs 450,000 people directly and indirectly. The hospitality industry in this island of pearl holds tremendous potential for economic growth, job creations, and cultural exchange,” he added.

He also pointed out more women should be attracted to the industry and advocated for the use of technology in hospitality sector to attract the younger generation.

The newly appointed Chairman Ramesh Dassanayake spoke about the challenges faced by the industry, including the reluctance of youth to join the sector. . Dassanayake expressed concerns over the migration of staff between hotels and the overall ‘brain drain’ in the sector. ” We must maintain high standards in the hotel We must try to attract tourists to Sri Lanka, we must have with many facilities Hence, hotel schools and other professional institutions involved in skills development mustincrease their intakes,” he pointed out.

Chief Guest Sajith Premadasa emphasised the importance of eco tourism and said “We need to have an environmental policy related to tourism in place,” . .

The 32nd AGM of the Institute of Hospitality UK, Sri Lanka Chapter, was a testament to the strength and potential of Sri Lanka’s hospitality industry. The insights and commitments shared during the event set a new benchmark for the future.(ZC)

Pix by Thushara Attapathu

Life style

He recognizes human identity beyond boundaries of gender, race, nationality and religion.

Visit of Sri Gurudev to Sri Lanka

Humanitarian, spiritual leader and Global Ambassador of Peace Gurudev Sri Sri Ravi Shankar (Sri Gurudev) was in Sri Lanka on a three day tour on the invitation of the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka Dinesh Gunewardene. Gurudev who inspired a wave of volunteerism and service to moot one of the largest volunteer-based organisations in the world – The Art of Living – visited the various projects under the aegis of the foundation and launched twelve vocational and technical centers around the island. He was accompanied by thousands of followers from Sri Lanka and around the world.

Gurudev who visited Sri Lanka for the sixth time also had a first day cover launched in honour of his visit. He is a strong proponent of spreading happiness, using the unique Sudarshan Kriya, yoga, meditation and practical wisdom to unite people, empower individuals and transform communities. His programmes provide techniques and tools to live a deeper, more joyous life, while his non-profit organisations recognize the human identity beyond the boundaries of gender, race, nationality and religion.

The Art of Living which has more than 30,000 teachers and over one million volunteers across 180 countries has touched in excess of five hundred million people around the world. CNN called it “Life Changing” and The Washington Post headlined it, “Fresh air to millions”.

In Trincomalee, Gurudev met with war victims and had a heartwarming engagement with the children from the children’s homes run by the Foundation. He also visited the Koneswara Temple in Trincomalee and graced the Kumbhabhishekam at Seetha ecogPnize the human identity beyond the boundaries of gender, race, nationality and religion. Amman temple at Nuwara Eliya. He held discussions with the trustees on the progress of the foundation’s social service projects, while also holding a special event – Ekamuthuwa – attended by a large number of dignitaries and his devotees from around the world.

His time with the Prime Minister was spent discussing the prospects of unity in diversity and uniting Sri Lanka by adding happiness into the formula of living. In addition he had discussions with the Speaker of the Parliament of Sri Lanka Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, prominent business stewards and civil society leaders.

Life style

Bridal shows with opulence and luxury at The Epitome hotel in Kurunegala

by Zanita Careem

Envison your dream wedding day come to life at the Epitome Hotel, a prestigious city hotel in Kurunegala offering an unrivalled luxury rendors experience for weddings.

The venue is designed to embody opulence and luxury from all quarters for a spectacular wedding in kurunegala,Thier ballroom is the largest banquet facility in Sri Lanka It can be divided into six luxurious pillarless wedding halls on the ground floor and 25pax smaller banquet halls.

It can be easily named as a five star heaven in the heart of the city contributing to a myriad of immense experiences tailored to inspire and delight wedding experiences.

From opulent décor set up to exquisite table decor, lavish food, every detail is meticulously curated to spark your imagination and ignite creativity for a perfect wedding. The previous prestigious wedding shows season one and season two attracted large crowds

were unique events which gave the wedding vendors and potential clients had an opportunity to connect and interact with each other. Beyond being a showcase it was a chance for the wedding vendors to unite and contribute to the vibrancy of the wedding industry. The wedding show covered all area of the bridal industry providing a comprehensive variety of bridal supplies from Sri lanka and became the most popular bridal exhibitions in Kurunegala.This bridal exhibitions allowed brides and grooms to experience first hand the products and services available from suppliers in Sri Lanka

These wedding shows held at The Epitome created a benchmark and gave an opportunity for vendors to create connections to the utmost satisfaction said Harshan Lakshita Executive Director. of the magnificent Hotel

Our wedding shows featured experts and professionals in every field‘ It covered all areas of the bridal industry provided a comprehensive variety of bridal supplies from Sri lanka and became most popular bridal exhibition in this region.We are always open to everyone to join us at our wedding shows in the future. It is an opportunity to discover the incredible talent within our local wedding and bridal vendors to make meaningful relationships and plan thier special day at our breathtaking hotel The Epitome said General Manager Kavinda Caldera

The Epitome Hotel’s bridal show which will be held end of June will buzz with great ideas,advice and inspiration for all those who plan thier dream wedding

…….

The Hotel Epitome’s Wedding Season 3 will marked excellence, celebration and inspiration for those in the wedding industry. The exhibition halls will resonate with ideas on exquisite bridal wear to decor, florists , photography etc and showshowcase the rich tapestry of talent within the local wedding industry. .